Welcome to the seventh of 12 articles revealing -- for the first time ever -- material cut from Star Wars: The Essential Guide to Warfare before its April 2012 publication. Each section will be preceded by brief comments discussing why the material wound up on the cutting-room floor.

THE ARMORY: CLONING TECHNOLOGY

Jason Fry: I like this overview of cloning, which attempts to construct an interesting narrative while addressing contradictions in established material. For me, that’s the real test of a “retcon” -- it has to be a satisfying read for newcomers, and not just appeal to hardcore fans who are well-versed in the source material. I think this does that -- the reader feels sympathy for the plight of the clones, and hopefully finishes the piece with an opinion about the morality of cloning. If space hadn’t been at a premium, I would have been happy to include this in Warfare. But space was at a premium, so I decided it was better to use our precious pages to discuss what clones were doing rather than their origins.

Many species have experimented with cloning, which has long been a routine part of galactic civilization’s medical science. For instance, vat-grown clone tissue and organs allow medical droids to treat serious injuries and diseases without fear that their patients will reject the new tissue.

But there has long been the temptation to use cloning to create what are effectively organic droids. Clones have been created to work in dangerous conditions, with their bodies altered to better survive exposure to corrosive atmospheres, radiation or extremes of pressure or gravity. They have been bred to serve as miners and deep-water divers, to live miserable lives as subjects of medical experiments, and to amuse the decadent as gladiators. And for millennia they have been created to fight wars.

All cloners faced the same challenge: Few customers had any interest in allowing clones to grow and age normally, wanting full-grown organics as quickly as possible. Solving this problem proved far more difficult than altering bodies through genetic manipulation. Growth acceleration caused few problems with the physical development of clone bodies, but the mind was another matter. The brains of clones grown according to an accelerated timetable often failed to develop normally. Severe retardation – sometimes ignored by unscrupulous cloners -- was a frequent side effect. So were mental instabilities -- many accelerated-growth clones proved insane, often dangerously so.

Cloners sought to solve this puzzle in any number of ways, but by the final years of the Republic two very different approaches seemed most promising.

The Kaminoans kept growth acceleration on a relatively low throttle, typically bringing a clone to maturity at twice natural speed, and educated and socialized clones through “flash training,” an intensive regimen heavy on holographic simulations. Kamino’s clones required more time and credits to bring to market, but were generally high-quality soldiers and workers, with the vast majority of mentally unstable specimens filtered out before delivery to buyers.

The Kaminoans kept growth acceleration on a relatively low throttle, typically bringing a clone to maturity at twice natural speed, and educated and socialized clones through “flash training,” an intensive regimen heavy on holographic simulations. Kamino’s clones required more time and credits to bring to market, but were generally high-quality soldiers and workers, with the vast majority of mentally unstable specimens filtered out before delivery to buyers.

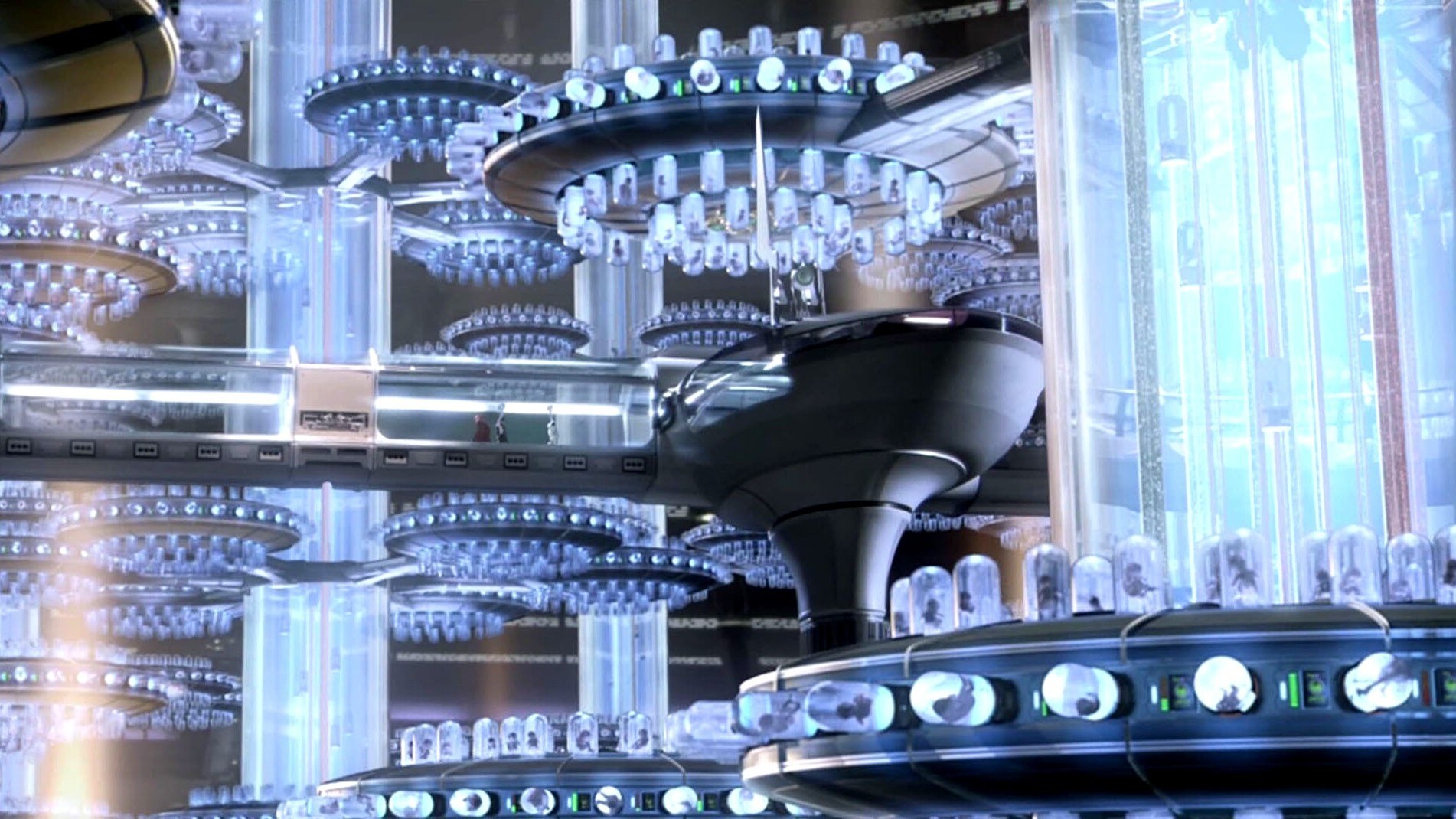

The other approach, used most effectively by the Arkanians after they incorporated a number of other cloners’ techniques, was known as “flash pumping.” The Arkanians developed clone bodies as quickly as possible, driving them to rapid maturity in Spaarti cloning cylinders, four-meter-high tanks that suspended the developing clone in a protective, nurturing gelatin. The Arkanian method left the cerebral cortex a blank slate until late in the cloning process, when huge amounts of knowledge and memories were implanted by directly connecting clone brains to computer systems. During the final years of the Republic, the Arkanian method cut production time of a mature clone to as little as a year. But there was a price to pay: Many more Spaarti clones exhibited mental instabilities, and they had trouble thinking creatively or adapting to situations that hadn’t been flash-pumped into their brains. “Clone madness” exhibited by Spaarti specimens took many forms, but among the most harrowing examples were flashbacks to “tank time” suspended in nutrient gelatin, and paranoid delusions that clones, non-clones or all other organics were droids, ghosts or evil spirits.

While the Republic’s initial clone orders were filled by the Kaminoans, Supreme Chancellor Palpatine authorized a secret cloning facility on Coruscant’s moon Centax-2, using Arkanian methods to create another army of Fett clones. These Spaarti-grown clones first saw extensive action during the Battle of Coruscant, and their Kaminoan brethren claimed they were poor soldiers with only a rudimentary grasp of battlefield tactics.

Late in the war, a Senate decree confined military cloning to a handful of Republic facilities; banned cloning of sentients for military purposes, with a few closely regulated medical exemptions; and forbade the purchase of sentient clones, the employment of cloning specialists and the sale of cloning equipment. But the intent of these laws wasn’t to rid the galaxy of cloning; rather, it was to establish a monopoly on the practice.

But while cloning became a clandestine science after the rise of the Empire, research into its techniques never ceased. In top-secret facilities, shadowy clonemasters conducted new experiments, including efforts to create Force-sensitive prime clones. And Grand Admiral Thrawn discovered that using ysalamiri to sever a developing clone’s connection to the Force allowed mentally stable clones to be created in just weeks -- a discovery he sought to turn to his advantage in his war against the New Republic.

MEMO FROM KAMINO

Jason Fry: If the last three sentences of this next piece’s first paragraph seem familiar, you’re not losing your mind. They’re from the opening of a chapter in Karen Traviss’ Republic Commando: Hard Contact, a novel I really like. I was intrigued by that passage and wondered what the context might be. In arriving at an answer, I also tried to address something else that had intrigued me: Why would anyone create an army of clones that could reproduce? This was one of my favorite pieces written for Warfare; cutting it really hurt and I’m very pleased to be able to share it at long last.

Internal memo penned by Hali Ke, senior research geneticist, Kamino, 27 BBY:

It is truly a pleasure to be producing humans again – and this time with a budget that allows us to linger in the twists and turns of that fascinating genome. Of all the species I have examined and augmented, humans may be my favorite. Humans offer us the greatest possibility of success side-by-side with the ever-present prospect of failure – and the difference may be the smallest snip of genetic code. This is the true art of genetic selection and manipulation. A human is naturally a learning creature, but is also violent, selfish, lustful, and undisciplined. So we must walk the knife edge between suppressing the factors that lead to disobedience and destroying the capacity for applying intelligence and aggression.

Humans are simultaneously capable of extraordinary viciousness and extraordinary acts of kindness and altruism. In attempting to understand the mental processes and constructs that have sprung from their tangled genetic code, I have interviewed and psychoanalyzed humans from both ends of this broad spectrum. I've spoken -- at a safe remove -- with a pirate from the Fair Hollis system who lacked the ability to see other organic beings as anything other than objects, and with Kardavan penitents who had spent their entire lives attempting to ameliorate the suffering of beings with whom they shared no bond of kinship or community. Any attempt to summarize the habits, attitudes and psyches of humans would either be so lengthy as to defy useful summary, or so general as to be useless.

That said, there are qualities essential to humans -- ones that emerged so far back in their history that are foundational aspects of the species. Above all else, humans are adaptable -- adaptable in terms of physiology, mentality and society. Their genome is remarkably elastic: Selection pressures need a few millennia at most to engage new genes and reshape their bodies in response to environmental changes, as the galaxy’s countless near-human populations attest. Human societies, meanwhile, are so divergent that two human populations can have more in common with neighbors of other species than they do with each other. I am aware of many theories for why humans dominate the galaxy, but in my view the answer is simple. Humans succeed because their societies and even their bodies morph quickly in response to a dizzying range of conditions.

I have now logged many sessions with our prime clone Jango Fett, and concluded that he embodies his species’ contradictions. He is a killer many times over, ending the life of others without hesitation if paid to do so, yet his anger was obvious when I suggested he lacked morality. He is one of the most able, competent humans I have ever observed, remaining calm in situations that would leave most organics helpless with terror. Yet he witnessed horrors in his childhood that he will not discuss, and around which his mind has constructed apparently impenetrable barriers.

Jango is given to solitude and affects a disdain for human relationships and connections, yet when he agreed to help train our army, he immediately summoned a band of mercenaries who shared his background. And, of course, there is the matter of his fee: Jango seemed barely to care for the considerable sum of five million credits, but was adamant that we create an unaltered clone of himself, whom he now refers to -- without a trace of self-consciousness -- as his son. I have seen him return to Kamino after killing men for credits, wash the blood out of his starship’s hold, and an hour later be gently talking and playing with young Boba.

The clones we are training will not, of course, be Jango Fett -- we have augmented their genomes to make them superior soldiers, with greater lung capacity, more fast-twitch musculature, improved stamina and better recovery times. We have eliminated physical defects such as susceptibilities to environment allergies and a mild astigmatism. Our clones will be more docile than Jango, less given to anger and more inclined to group identity. They will, unavoidably, lack some of Jango’s tactical brilliance and improvisational genius – but this should be offset by a greater ability to operate effectively as a combat unit.

But for all that, we must expect a certain number of aberrant behavioral events in units approved for deployment to the customer. Some of Jango’s independence and defiance will surface, as it is buried too deeply in the genome to extract without eliminating the qualities we value. And some of our units will display other quirks, as Factor H asserts itself. Jango insists these displays of individuality and unpredictability will make our units more effective, not less, and I agree. Factor H may be frustrating to those who track aberrance rates, but I predict our combat trainers will find a strong correlation between deviations from behavioral patterning and effectiveness on the battlefield.

I should also like to address a final point of contention, one I thought had been put to rest during our reviews of the initial Fett prototypes. This, of course, is the question of why these clone units were not engineered to be sterile as per standard procedure.

The answer goes to the heart of why Factor H cannot and should not be eliminated. Two recent human projects – the miners created for Tarshan Ring Excavations and the infiltration squads requested by the Lords of Purala IV -- began with trials of sterile clones, as requested by both customers. In both cases the clone prototypes displayed much higher rates of mental instability, poor unit cohesion, an inability to adapt and think creatively, and decreased aggressiveness in battlefield sims. A number of corrective measures were employed -- synthetic hormones, rewiring cortical pleasure centers and dietary additives -- but all cases improvement was minimal.

It is certainly irregular to recommend that we deliver an army of clone units able to reproduce. But the TRE and Puralan experiments, as well as my experience with humans, tell me that we have no choice if we also want an army that can fight effectively. I propose that we mitigate the situation through the following measures:

- channel the clone units’ normal human impulses for pair-bonding and reproduction into unit cohesion and mission preparation;

- advise the customer to minimize contact with civilians and mainstream human society in crafting the clone units’ daily routines;

- limit knowledge of the clone units’ reproductive capacity to military officials on a strictly need-to-know basis; and

- pursue bioengineered contingency planning in the event that a mass emergency reconditioning is required. (Bioengineering could also be useful if further behavioral modification is requested.) This latter option must be pursued with the utmost secrecy due to its possible exploitation by the customer’s enemies.

By following this program, I am confident that incidents of clones reproducing will remain minimal, and their impact further minimized through contrafactual public communications by the customer. And in the meantime, we on Kamino will of course continue to try to unlock this puzzle – and the others that come with our work on such a fascinating, confounding species.

THE ASSEMBLY LINE

Jason Fry: This one was really an homage to the Medstar duology by Michael Reaves and Steve Perry, of which I’m a big fan. It hurt to cut it, but the focus had to stay on the battlefield. I’m glad to see it appear here.

Erich Schoeneweiss: As with the two cut pieces above, this would have posed a real dilemma for me while editing. When facing the need to cut text because the manuscript is too long, some of the questions you might ask yourself are: Is this piece worthy of staying in the manuscript? Does it add essential information? Is that information interesting to both casual readers and hardcore fans? Does it cover new ground or is it repeating information the author already presented? Is it relevant to the book’s subject? The chapter’s subject? Jason made the choice to cut all three of the three pieces you read today before submitting the manuscript to me, which proved lucky on my part as I might still be contemplating their fate. And even luckier for all of us, you get to read them now.

For a Republic soldier seriously wounded on the battlefield, the race was on: Could he or she be stabilized, evacuated and treated in time?

For clone troopers, the initial alert was often broadcast by the trooper himself -- or, rather, by vital-signs monitors in his helmet. In other cases, a fellow soldier might call in the injured soldier’s location, automatically appending a geolocation tag to the report.

Many Republic units went into battle accompanied by medical droids, with Cybot Galactica’s IM series emerging as the standard battlefield models. IM-series droids swooped back and forth across the battlefields on their repulsorlifts, dodging enemy fire, stabilizing wounded soldiers and dragging them to safety while speaking in a calm, soothing voice. IM droids’ effectiveness, coupled with soldiers’ natural bent toward superstition, led many Republic units to consider the droids members of their units, painting them in regimental colors and tapping their bodies for luck before deployment.

Another battlefield medical droid, Medtech Industries’ FX-6, was treated less reverently: The FX-6’s plasteel armor shell allowed it to work in combat settings, but its programming was to save lives as quickly as possible and by any means necessary, without communicating with patients or considering their suffering.

After initial treatment by a medical droid, a wounded soldier would be whisked away from the battlefield by a medical speeder or a medlifter troop transport, with a number of different models seeing service. Aboard the medlifter, a medical droid or organic medic would determine the severity of the soldier’s injuries and the likelihood of survival, prepping him or her for intake at a Republic Mobile Surgical Unit, or RMSU.

RMSUs -- invariably referred to as rimsoos -- were small field hospitals for treating battlefield casualties. There, organic surgeons and medical droids worked together – often under frantic conditions – to save soldiers’ lives, a daily and even hourly task that overworked surgeons grimly called “the assembly line.” Droids or medical aides would strip incoming critical cases of armor and equipment and deliver them to the operating table. There, surgeons and a variety of medical droids -- 2-1Bs, MD-series droids, FX-series units and DD-13 “chopper” droids -- would deploy instruments and technologies in an effort to save the wounded. Handheld bio scanners diagnosed injuries, antisepsis fields prevented infection, laser scalpels opened up damaged bodies, glue stats closed them up again, and pressor fields kept damaged arteries closed. Replacement organs and body parts, either made of cloned tissue or taken from dead clones, were close at hand in nutrient tanks. (The surgical ward where dead clones “donated” usable organs for the tanks had the macabre nickname of the discard pile.)

After surgery, soldiers would be taken to a recovery ward or, for more severe cases, a bacta tank. Those who needed more than a few days to recover were transferred to a MedStar- or Pelta-class medical frigate, and often brought to one of the Republic medical stations. Aboard these spoked space stations, medics cared for tens of thousands of soldiers at a time, working diligently to repair bodies and minds so units could return to the battlefield.

The status of medical facilities and hospital ships was one of the biggest flashpoints of the Clone Wars. The Republic’s MedStars originally lacked not only weapons but also basic defensive capabilities, but some Separatist commanders -- most notably General Grievous -- deliberately targeted MedStars, RMSUs and medical stations, giving no quarter to the wounded or those trying to save lives. Such strikes served to stiffen Republic resolve that soldiers, not negotiators, would be the ones to end the war.

Star Wars: The Essential Guide to Warfare is the definitive guide to the ultimate intergalactic battlefield. Packed with original full-color artwork, it includes facts, figures, and fascinating backstories of major clashes and combatants in the vast Star Wars universe.