Welcome to the fourth of 12 articles revealing -- for the first time ever -- material cut from The Essential Guide to Warfare before its April 2012 publication. Each section will be preceded by brief comments discussing why the material wound up on the cutting-room floor.

THE WATCHMAN’S TALE

Jason Fry: This next piece is one of my favorite bits of writing that wound up on the cutting-room floor -- I think (or at least hope) it’s poignant without being overdone. That said, we were still in the deep past of the Star Wars galaxy, an era known only to hardcore fans and one that’s missing the more-familiar references that appeal to mainstream fans. I love the esoteric stuff, but too much of it is a risk in a book, and this piece felt like too much of that.

Erich Schoeneweiss: Once again Jason and I were dealing with an overabundance of material. My focus was on keeping the book moving forward and maintaining a fair balance between what a casual reader would want to read and what a more knowledgeable reader would want from the book. As Jason said, this is a nice poignant piece, but it doesn’t feel Star Wars and aside from the mention of Jedi at the end there isn’t anything that a casual reader would recognize as Star Wars.

Until its destruction in 19 BBY, the Caamasi Palace of Memnii was renowned among historians for its millions of first-person accounts by beings who had confronted violence during their lives. Among the oldest records preserved in the Palace was a Baragwin sense lattice imprinted by an anonymous Republic soldier assigned to Falang Minor shortly after the end of the Tionese War (circa 24,000 BBY). The lattice’s visual record is irretrievable due to the loss of the original algorithm used to encode it, but the audio remains audible. The following translation is derived from a copy in the possession of a traveling memnii exhibit at the time of Caamas’s devastation.

I grew up on Little Atullus, but my parents brought me to Okator VIII when I was a boy. They sunk their life savings into land promised by some hotshot traders out of Brentaal. There was a lot of that on Little Atullus then – talk that a better life awaited you on the unspoiled worlds beyond the Rim.

And it was kind of true. Okator VIII wasn’t lush -- it was chilly and the soil was poor. But land was cheap, the soil could be improved with effort, and the native whellays were gentle beasts that took easily to domestication. That was my first job, while my parents built the cabin and cleared the fields: go into the woods and put out whellay bait. I caught six the first day and thought I was the god of the forest. Then I named them all. My parents hadn’t told me that whellays were destined for the dinner table. There’d been so much to do, I guess it hadn’t occurred to them.

I was lonely at first, but eventually I forgot about Little Atullus, except in dreams. And I got used to farm life. Let the whellays out at dawn with a shakwulf to tend them, weed the saria, wait until the charsby pitchers sensed the midmorning sun and then stick siphons in them, always approaching from the shadow side so you wouldn’t get a quill in the hand. Harvest the nectar, then spend the rest of the morning loam-tapping for ripe galt-gourds. After lunch I’d whistle the shakwulf to bring the whellays home. Then I’d spend the afternoon currying their coats and checking their hooves, see if any were coming into estrus and consult the lineage-books for the best pairings. Unless it was shearing season, in which case we’d be in the barn into the night. Then dinner, repairs and lessons if I couldn’t get out of them. At first I only tolerated it. Then I realized I was happy. That I knew each of our whellays by the smell of his coat and the way he’d whicker. That I’d known Brun, my favorite shakwulf, from his first moment as a blind pink pup, and he loved me more than anything in the galaxy. I knew every tree in our woods, every outcropping in the hills, every dip and ridge we hadn’t leveled out in the charsby orchards.

We knew about the war, of course. We’d hear the latest when we went into town or got a good signal on the subspace vox. I knew about the Tionese, that they’d done awful things to us and maybe we’d done awful things to them. I’d heard of Xim. He’d been eaten by the devil-slugs so they could gain his powers, but the Tionese claimed he would return from death to lead them.

But he’d been dead forever with no signs of coming back, and all of it was such a long way from Okator that I didn’t see how it mattered to us. We weren’t even on the Perlemian; sometimes the beacon at Uthtara would break down and you wouldn’t see a tradeship for weeks until it got fixed.

I heard that’s why they chose us. I heard they were tired of killing a few blocks worth of people on some city-world so big that the deaths were just a statistic. I heard they looked for a place where they could kill everybody. I don’t know how they picked Okator VIII. It doesn’t really matter, I suppose. It could have been a lot of places in the Divide. They could have picked Matabre, or Ilamna or Cortilium Major. But they didn’t. They picked Okator.

I was out in the forests with Brun tracking a lost whellay when I heard the first ship. I knew it wasn’t one of the tradeships or a courier on business from Hleua. The drive sounded different -- it had this weird, deep grumble to it. I didn’t see that one, but I saw the next one, and the third. They were copper-colored, with red sigils on the conning towers, and I knew they were Tionjacks.

The next thing I knew I was on my back and I couldn’t hear. I got up and saw the trees on the Pinson ridge had been flattened, pointing away from Derway Township. There was a pillar of black smoke beyond the ridge, and then the smoke washed over the ridgeline and hid everything. Brun was racing around me, and I could see him showing his teeth and howling, even though I could barely hear it.

Then Brun stopped and the spines on his back raised up. He stood stock still for a moment and then went streaking off through the trees, toward home. And I saw the glint of the Tionese ships above Duny Gap and Shillagh Hollow. Moving slowly, like they were looking for something.

I saw the flashes of the incendiaries and the dioxis flares, beneath the jacks’ bright bellies. I saw the gas billow up above Duny and knew that everybody there was dead. Then the flames came shooting up from Shillagh. And then I started to run, because now there was another glint above the ridge, above our valley.

The worst thing, I think, is that I saw the farm before the jack began its attack run. Brun had rounded up the whellays and brought them home. He’d been taught that danger was out in the woods, from nightscowls and things like that, and the farm meant safety. He didn’t know that now the opposite was true.

The jack ignited its plasma torch, and I saw Brun and the whellays running in circles. They were on fire. All I wanted was for them to be still, for it to be over. It took so long. And then the house was burning, and the fields. I saw each of the pitchers pop as its nectar boiled. And then the jacks were gone, their work done. It was three weeks before the courier came and found Derway destroyed by the pressure bomb. Another two before I was able to hail a scoutship. That was the last time I saw Okator.

As far as I know it was the last time anyone saw Okator.

They wanted me to go to Coruscant, to tell my story. But I refused. Instead I went to Abhean to enlist, and eventually they let me. Four months later, before I could get into the fight, Desevro surrendered. The war was over.

And now I’ve been here for 12 years. A Republic Guardsman, serving the Jedi watchmen. I monitor ship traffic, intelligence, transmissions -- everything that comes out of the Tion.

I don’t like Falang Minor. It’s cold and it rains all the time. There isn’t anything that will grow or any beasts to tend. And I don’t like what I do. It gives me too much time to think.

But somebody has to do it, and I’m that somebody. I didn’t choose it -- it was chosen for me, when the jacks came to Okator. I don’t hate the Tionese anymore. I used to. It made me feel sick all the time, so I made myself stop. But I don’t trust them. No one in the Republic should ever trust them. They need to be watched, and my job is to watch them. All of us here on Falang watch them. And we always will.

THE WAYMANCY STORM

Jason Fry: My friend and Essential Atlas co-author Dan Wallace invented the Waymancy Storm for a brief reference in Galaxy at War. I was intrigued by the name, and so for Warfare I used that long-ago war as an example of a paradigm shift in Republic technology. (It wound up in the section on Capital Ships.) I asked Dan to craft an in-universe document as a sidebar, eager to spotlight his uncanny knack for strange, evocative names and language. I loved the piece he wrote, but -- as with “The Watchman’s Tale” – looking at the manuscript it was clear that the early chapters were both too long and too heavy on relatively esoteric Star Wars lore. So, sadly, it got cut.

Erich Schoeneweiss: My thought on this -- and at the time I did not know Dan had written it -- was that the entire piece was written with the assumption that the reader was already familiar with the Waymancy Storm instead of educating the reader about the event. I told Jason that we either had to better explain what the Waymancy Storm was or find a compelling reason to keep it, otherwise it was a sidebar I felt we could cut. After reading it again I’m confident in the decision we made.

Oh, and I did suggest at the time that we save it and use it as an online exclusive. So I feel good about my Force-sense abilities and happy that Dan’s work is now available for you to read.

<10.30.7786 BBY>

Transcript of Chancellor Nagratha’s remarks on the occasion of the 25th anniversary of Victory in the Waymancy Storm:

Greetings, and my thanks to Chief Sergeant Sukko for his presence at today’s service. Thank you to all the veterans present and to all those watching on your homeworlds. It was your sweat and courage that won the victory we now commemorate.

Victory in the Waymancy Storm has been celebrated every year since that solemn, glorious day 25 years removed. It will be remembered long after I have left office and long after all of our lives have passed into history.

Victory brought liberation to the brave settlers of the Rim, and those settlers have since brought new generations into the galaxy. Fresh-faced, hopeful faces that live lives untouched by war. They are our legacy. They are the legacy of every Republic soldier who fought, every Republic settler who resisted, and every life that was left behind on the battlefields. Those sacrifices will never be forgotten.

What did the Waymancy Storm mean to the Republic? More than any conflict before or since, the Waymancy Storm found us outmatched in the technology of war. Though we outnumbered our enemies a hundred to one, the frightful killing machines wielded by tyrants absent of conscience inflicted terrible losses in our ranks.

The mercenary army of Whirl-Point-Six carried cannons that spat out hailstorms of energy so thick they appeared as constant beams of fire. The armadas of the Wives of Tingrippa sailed arrogantly between the Rim’s beacons, boasting that their weapons could puncture any Republic hull and that their shields could soak up any Republic counterattack.

As their onslaught continued, their bloodlust deepened. At Upper Brightday, 10 million settlers saw their lives extinguished as the land was put to the torch. The Republic defense of Barenth allowed a near-complete civilian evacuation at the cost of an entire battle group and its personnel, who never flinched in the face of their duty. At Sooncanoo Beacon, the enemy massacred every crewmember of the Fortieth Flotilla when a bold gambit to boost their shields failed and left them dead in space.

War is never welcomed. Our Republic wasn’t founded on blood, but on the principle of peace through cooperation. Yet this war was necessary. The Signatories of Waymancy had to be stopped. Some of their number believed in fanaticism, some believed in territorial cleansing, some believed in nothing at all beyond the cold logic of machinery. But the wholesale murder of settlers and their families? That could only be practiced by those who believed in evil.

Liberating the northern Rim was never in question. All Republic residents are equally valued, whether they make their homes on Coruscant or on Caursito. After mourning our losses, we citizens rose up as one to deliver our response.

Our uniformed ranks swelled with determined volunteers. The factories of the Expansion Region churned out armored galleons and crawler mechs. Spies and codebreakers worked day and night to interpret an ocean of intercepted data – my mother was one of the Squill Sifters. And deep behind a security barrier in an Axum shipyard, technologists struggled to reverse-engineer the weapons and starship generators the Navy had captured at Sif-Alula.

For while we in the Republic possessed an unquenchable fighting spirit, our enemy had a cold, automated edge. After studying our technology for a thousand years inside the Waymancy Hollow, the Sisters of the Machinesmith had improved on our designs in nearly every way. Their ships could fly farther and faster. Their energy shields could withstand anything fired by our battleships. Their pulse-wave weapons packed a rapid-fire, armor-piercing punch whether mounted on a cruiser’s hull or carried in the clawed fist of a Muzaran thug. No, we would never have given up. But without the scientific breakthroughs made on Axum, the cost in Republic lives would have been far greater.

And you did it. We -- the Republic -- did it. Armed with boosted pulse-wave carbines, the Republic rocket-jumpers routed the Neshtabine nest on Tantara. Bearing an experimental shield generator and a shimmering new energy skin, the cannonship Squintpipe threaded the enemy formation at Immalia, halting the orbital bombardment and sending the surviving ships scurrying for the jump beacon. Chief Sergeant Sukko was among those who scaled Mittoblade’s magnetic cliff, where he helped trigger the collapse of the Clowse Glowstack despite losing both legs to a Doshan raider.

In the end, we all know the story of the final Republic push and the atrocities unleashed by our enemies. But what we choose to remember is the story of the war as told through the soldiers who refused to desert their fortifications at Paig, or the fleet element that held the line at the Second Battle of Brightday. We remember the veterans who have gathered today, and whose brothers and sisters in arms have accompanied them in spirit.

We remember the ravaged worlds of the northern Rim that now thrive. Our shouts of triumph then echo in the cries of every baby born into a Rim family now. A hyperspace sinkhole is all that remains of the Waymancy bridal seat, and on a thousand Rim worlds the flag of the Republic flies high. A thousand more will join them, with a thousand more right on their heels. This is our reward, bought with service and sacrifice, with blood and hardship.

Today we salute those who earned that reward, and we honor the memories of those who have gone to their rest. In the name of the Republic, may peace reign eternal.

ROCKET-JUMPERS

Jason Fry: A relatively straightforward section, following the lead of Dan’s work for Galaxy at War. As written here, it was very connected to the relatively esoteric lore the book was already too heavy on, and so a relatively easy cut – one I think I made before sending the manuscript on to Erich. In hindsight, a slight rewrite would have made this work well in the book – we could have cut the history back and refocused the piece on tactics and the connections with clone-trooper and stormtrooper units. But hey, that’s why they call it hindsight.

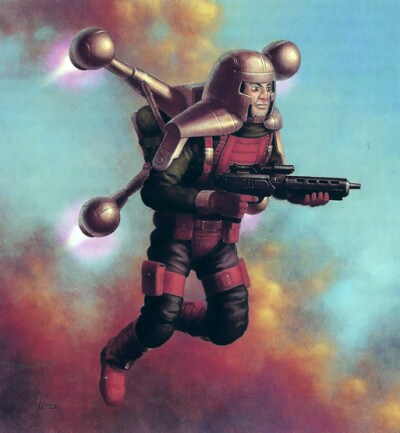

Erich Schoeneweiss: I don’t recall reading this – it’s cool stuff I would have found a way to keep. And I definitely would have commissioned art for it. I can just imagine a cool piece showing the Rocket-jumpers facing off against Juggernaut war droids over Monument Plaza.

Officially known as the Rocket-Jumper Elite Advance Unit, rocket-jumpers were the among the best-known and most-loved units of the Republic Army for millennia, winning accolades for their astonishing bravery in battles “from the sands of Socorro to the seas of Seffi,” as their famous motto puts it.

Rocket-jumpers used jet packs to penetrate deep into enemy territory and set up airheads – staging areas where troops and heavy equipment could be shuttled in. The unit had its origins in earlier forces that saw action during the Pius Dea Crusades, using powered paragliders to reach their goals. Around 11,000 BBY, advances in jet-pack technology led to the unit’s reinvention. Rocket-jumpers played a key role in the Jedi victory over Pius Dea troops at Ord Carida, and fought bravely in such conflicts as the Second Herglic Feud (9757 BBY), the Waymancy Storm (7811 BBY), the Gank Massacres (4800-4775 BBY), and The Quesaya Border Conflict (4007 BBY).

One of their best-remembered actions was actually a defeat, however: In 4015 BBY, during the Great Droid Revolt, squads of rocket-jumpers defending Coruscant were intercepted and wiped out by rogue Juggernaut war droids in the skies above Monument Plaza as heartbroken citizens watched. (Ironically, it was a much-decorated veteran of the rocket-jumpers -- Supreme Chancellor Vocatara -- who commissioned the first Juggernauts to help turn the tide during the Gank Massacres.)

In 1000 BBY, the Ruusan Reformation led to the abolition of the rocket-jumpers, but their tactics lived on within special units of sector and planetary defense forces, as well as Mandalorian raiders. The Republic clone army studied rocket-jumper techniques and used its jet troopers in many conflicts of the Clone Wars, with the jet troopers evolving into the Stormtrooper Corps’ air-trooper divisions.

A typical mission might see rocket-jumpers drop at high altitude from Republic troop carriers, freefall until less than 100 meters from the ground, then ignite their jet packs and glide down to a gentle landing. When bypassing enemy units, rocket-jumpers would perform low-altitude hops by squad, maintaining tight formations and coordinating fire to clear landing sites. They proved so effective at such missions that the Republic called upon them for any task that required a quick strike at a difficult target: reconnaissance, targeted assaults on enemy emplacements, VIP extraction, combat and rescues in the atmosphere or zero-gravity. Rocket-jumper units were also assigned to the Republic Navy, performing zero-G jumps to reach enemy warships, penetrating their hulls with explosives and taking over the ships or destroying them. During the units’ heyday, it’s said that less than 8 percent of applicants passed the grueling initiation required to become a rocket-jumper.

Rocket-jumpers knew that their assignments were inevitably dangerous and would often prove deadly, and few expected to live long enough to retire and live the good life on some quiet world. Therefore, rocket-jumpers were famous for living life to the fullest – brawling in seedy cantinas, risking their lives on foolhardy dares, and striking up doomed romances. Even most of those who caught a rocket-jumper on a rowdy evening continued to idolize them for their bravery and dashing ways, however. Countless children of the Republic grew up watching holos about their exploits and recreating them with super-articulated toys, dreaming that one day they too might plummet from the belly of a troop carrier while the Republic’s enemies waited below.

Star Wars: The Essential Guide to Warfare is the definitive guide to the ultimate intergalactic battlefield. Packed with original full-color artwork, it includes facts, figures, and fascinating backstories of major clashes and combatants in the vast Star Wars universe.