On his 27th birthday in 1971, George Lucas flew to London. It had been a tumultuous period. His debut feature film THX 1138 had been released by American Zoetrope and Warner Brothers, and was even selected for the Director’s Circle at the Cannes Film Festival (his reason for going to Europe on a shoestring budget). But the film’s lackluster performance at the box office had combined with existing issues between Zoetrope and Warner’s. On the way to London, Lucas and his then-wife, Marcia, stopped in New York to see Francis Ford Coppola who was directing an adaptation of a popular gangster novel for Paramount, The Godfather (1972). Coppola was directing the film in part to help rescue Zoetrope from its dire financial straits.

Arriving in London on May 14, his first time in the city, Lucas phoned movie executive David Picker from United Artists, and managed to convince him to provide seed money for the project that became American Graffiti (1973). Newly unaffiliated, Lucas was in the process of starting up a company to be named Lucasfilm as a means of shepherding his own projects. Traveling south from London, the young filmmaker arrived in Cannes to meet with Picker, who asked him about any other projects he might have in mind.

“I said, ‘Well, I’ve been toying with this idea of a space-opera fantasy film in the vein of Flash Gordon,’” Lucas would be quoted in J.W. Rinzler’s The Making of Star Wars. “And he said, ‘Great, we’ll make a deal for that, too.’ And that was really the birth of Star Wars. It was only a notion up to then — at that point, it became an obligation [laughs]!”

Though the ancient city on the River Thames is only a backdrop in this episode, it’s fitting in hindsight to see how London and its surroundings are wrapped up in the story even at such an early stage. Though Lucas was still very much the kid from California’s Central Valley, the “obligation” to make Star Wars would take him overseas for long stretches of time, and most of all to the United Kingdom.

A national industry

The principal photography of Star Wars: A New Hope (1977) would be centered in England as a “solution to a multi-faceted problem,” as producer Gary Kurtz would explain. 20th Century Fox restricted A New Hope’s budget as much as it could, forcing Lucas and Kurtz to ensure that each dollar (or pound) went the longest way. Not only was England more affordable, it was closer to North Africa, where Lucasfilm planned to shoot on location in the deserts of Tunisia.

But it wasn’t only that English crews and soundstages were less expensive. The United Kingdom had one of the most experienced national film industries in the world, with a strong tradition of masterpieces from The Red Shoes (1948) and The Third Man (1949) to Bridge on the River Kwai (1957) and Lawrence of Arabia (1962). So called “genre pictures” were big business, as well, from the Gothic horror movies made by Hammer Film Productions and the stylish, action-oriented James Bond series. The American director Stanley Kubrick (16 years Lucas’ senior) had emigrated to make his films there, including 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) and A Clockwork Orange (1971).

A New Hope would benefit from the experienced artisans, craftspeople, and technicians who’d contributed to scores of celebrated British films. In particular, Lucas was keen to find the right cinematographer. After interviewing a number of his favorites, he landed on Gilbert Taylor (usually known as Gil), who had shot dozens of films since the late 1940s, including two of Lucas’ favorites: Kubrick’s Dr. Strangelove and Richard Lester’s A Hard Day’s Night (both 1964).

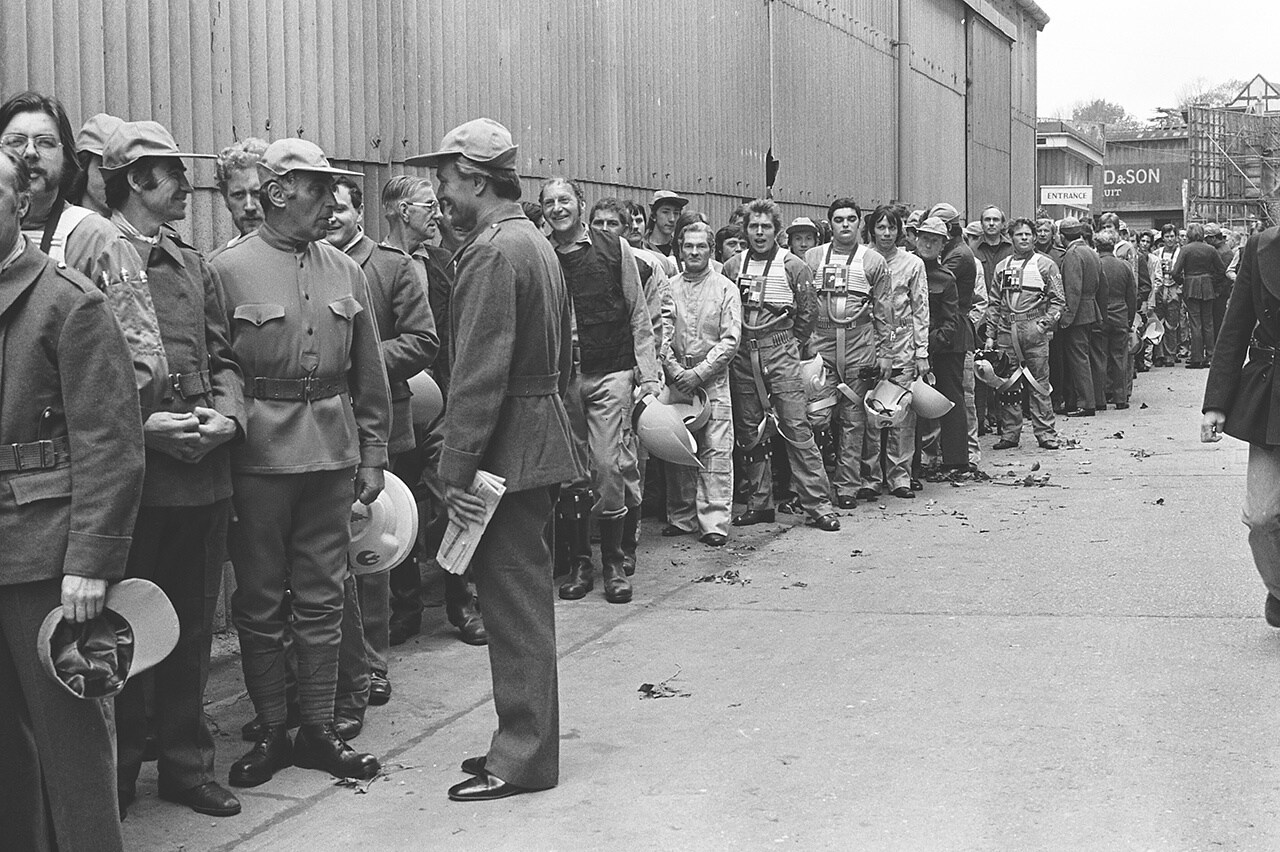

There were other veterans of Kubrick films like production designer John Barry and makeup artist Stuart Freeborn, the latter of whom had created the ape costumes in 2001 and would subsequently make Chewbacca’s costume (along with the help of his wife, Kay, and son, Graham). Younger contributors included costume designer John Mollo and art director Norman Reynolds, who brought with them dozens of local craftspeople to physically make the countless sets, props, and costumes. These tangible elements of the Star Wars galaxy were the product of the United Kingdom’s experienced studio shops.

Home away from home

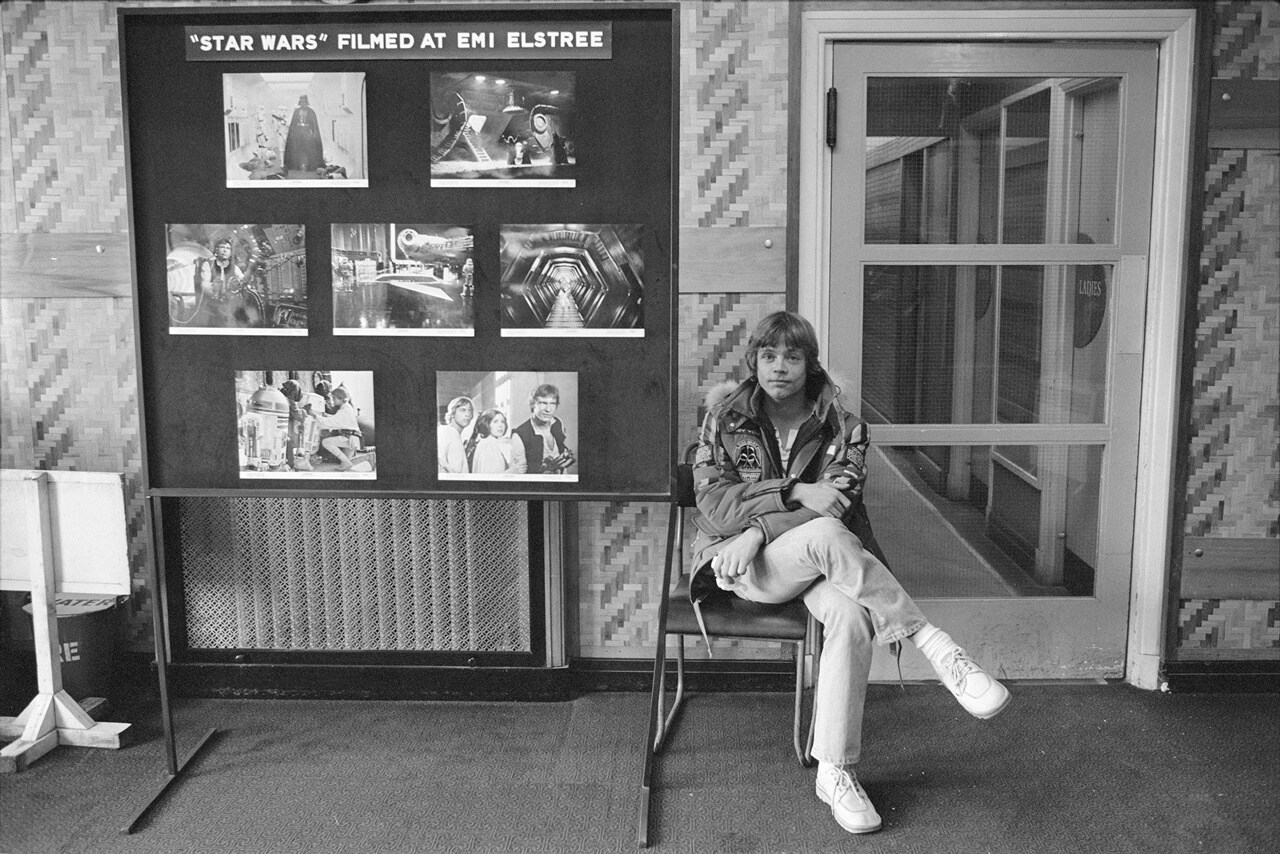

Over the years, a number of movie studios had been constructed between the English neighborhoods of Elstree and Borehamwood. Just north of London, they formed an elaborate complex of separate operations. One of the oldest studios dated back to the silent filmmaking period of the 1920s, and by the time of the Star Wars production in 1976, it was operated by the media conglomerate EMI. Under the supervision of producer Robert Watts, EMI Elstree became Lucasfilm’s home away from home for the next 12 years, from A New Hope through 1989’s Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade (that includes the 1986 Lucasfilm co-production, Labyrinth, directed by Jim Henson, who’d previously led his crew on The Muppet Show at the nearby Elstree BBC studios).

EMI Elstree even expanded thanks to Star Wars. A new stage — named for the series and pre-financed by Lucasfilm — was constructed especially for Star Wars: The Empire Strikes Back (1980). At 250 feet long and 45 feet high, it housed the full-size Millennium Falcon which had been made in pieces and trucked in from the Welsh coast. Back on A New Hope, Elstree couldn’t provide such a large space, and so the production used Shepperton Studios (south of London’s Heathrow Airport) for the sequences at the Rebel hangar and throne room.

In the mid-1980s, not long after Lucasfilm had completed all three original Star Wars productions at EMI Elstree, George Lucas was back at the studio visiting his friend Walter Murch, then directing Return to Oz (1985). On a neighboring Elstree stage, a small crew was busy making a feature drama called Dreamchild (1985). There Lucas met Rick McCallum, the film’s American-born producer who’d found success in the United Kingdom. They would form a partnership on the television series, The Young Indiana Jones Chronicles (much of its first season was made in the U. K.), and later agreed to make the Star Wars prequel trilogy together.

For Star Wars: The Phantom Menace (1999), McCallum settled on Leavesden Studios, a former aerodrome built to construct military aircraft during World War II. Further removed from London, its large hangars had been converted into a movie studio for the James Bond entry, GoldenEye (1995). The Phantom Menace centered its principal photography and pick-ups there between 1997 and ’98, once again pulling on the local industry of craftspeople and technicians to fill out the crew. And even after Lucasfilm relocated to Sydney, Australia for Star Wars: Attack of the Clones (2002) and Star Wars: Revenge of the Sith (2005), the Star Wars crew returned to England for pick-ups at Shepperton, Ealing Studios (where Obi-Wan Kenobi actor Alec Guinness had once made a number of comedies in the 1940s and ‘50s), and even Elstree itself.

Although the various Star Wars crews had spent years working at familiar English studios like Elstree, the production team for Star Wars: The Force Awakens (2015) settled into a location brand new to the saga. Younger than Elstree by nearly ten years, Pinewood Studios in Buckinghamshire had arguably become the most iconic of England’s movie-making facilities. It was home to the James Bond series among countless others like David Lean’s Oliver Twist (1948) and the musical adventure Chitty Chitty Bang Bang (1968). As of this writing, it’s now hosted more Star Wars productions than any other studio location in the world. In addition to all of the new Star Wars feature films, Andor (2022) and The Acolyte have also been made there (along with Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny).

Back in 2014, Lucasfilm finally established a permanent home in the United Kingdom with the opening of Industrial Light & Magic’s London studio. England has not only been home to iconic movie studios, but also a fair number of stalwart visual effects houses. Joining this existing community in London, the ILM studio is now one of the company’s largest offices, and among its earliest major projects was Star Wars: The Last Jedi (2017).

Local spots

Star Wars productions in the United Kingdom haven’t been limited to soundstages and visual effects facilities, however. England’s ancient forests have stood in for locations in the galaxy far, far away, including Whippendell Woods not far from London, where Qui-Gon Jinn and Obi-Wan Kenobi meet Jar Jar Binks, and Gloucestershire’s Puzzlewood where Kylo Ren and Rey had their first violent confrontation.

Further afield was Scotland’s Cruachan Dam, a hydroelectric power station built on Loch Awe in the southwestern Highlands. This industrial marvel became a sprawling Imperial facility in Andor, wherein Cassian and his rebel coconspirators attempt a dangerous heist. Another Imperial base was the high-security vaults on Scarif, seen in Rogue One: A Star Wars Story (2016). The Canary Wharf Station of the London Underground was transformed by the production art department to become an extended corridor within the facility.

Not far from ILM London’s offices is a different sort of locale with Star Wars heritage. Abbey Road Studios (another former EMI operation) has become iconic in the history of music recording for many reasons, not the least of which is the collaboration between composer John Williams and the London Symphony Orchestra on multiple Star Wars scores. During work on The Empire Strikes Back, Williams explained that London had become “the front rank” in orchestral recording. “[You] have the combination of a wonderful pool of players and tremendous technical expertise — plus, a closeness to the film community. The British film industry is based in and around London, so it is the hub of all activity.”

The Star Wars community

As in all endeavors at Lucasfilm, it’s the people who make the difference. From the beginning, the people of the United Kingdom have played an integral role not only in the creation of Star Wars, but in its reception. British audiences had to wait until December 27, 1977, before they had the chance to see A New Hope (more than seven months after their American counterparts). A passionate fan community grew quickly, and by the release of Empire, the energy was palpable. The day before the sequel’s release in May of 1980, stormtroopers roamed London passing out “Happy Empire Day” buttons. The movie itself would play in the city for over six months.

In 2007, the U. K. became the first country after the United States to host Star Wars Celebration. Two years removed from Revenge of the Sith (2005) and the presumed “ending” of the saga, thousands gathered along the River Thames at ExCel London, demonstrating that Star Wars fandom wasn’t slowing down, but in fact, growing. Celebration came back to London in 2016, and a third gathering in April 2023 will soon make it a trilogy of British conventions over the past 16 years.

Check out StarWarsCelebration.com for more information. Star Wars Celebration Europe 2023 will be held April 7-10, 2023, at ExCeL London in England.