Star Wars: Episode I The Phantom Menace arrived on May 19, 1999, to a degree of anticipation and hype rarely seen before, or since, for a movie. There was good cause. It was the first new film in the Star Wars saga since 1983’s Return of the Jedi, and the kickoff of the prequel trilogy, which promised to tell the story of how Anakin Skywalker turned to the dark side and became Darth Vader, while the Emperor rose to power. George Lucas himself wrote the script and was back directing for the first time since 1977’s Star Wars, and the movie became a giant leap forward in digital effects -- including a record number of effects shots and a major CG character in Jar Jar Binks. “All of the Star Wars movies, in one way or another, are about me and my take on the world,” Lucas tells StarWars.com. That might be especially true for The Phantom Menace, a colorful mashup of Kurosawa, political intrigue and history, racing, and family. As The Phantom Menace celebrates its 20th anniversary this month, StarWars.com spoke with several of its greatest architects to tell the story of how it came to be, and to reflect on it today.

Every Saga Has a Beginning

Following the release of Return of the Jedi in 1983, George Lucas’s commitments to Star Wars, at least in film, were complete. In the intervening years -- dubbed “The Dark Times” by fans -- Star Wars was largely absent from the public consciousness. Lucas, for his part, spent the time raising his family and somewhat quietly shepherding the evolution of digital effects with Industrial Light & Magic, resulting in innovations like the liquid-metal T-1000 of Terminator 2 (1991) and the mind-blowingly lifelike dinosaurs of Jurassic Park (1993).

Finally, on November 1, 1994, Lucas sat down to write Episode I.

George Lucas, The Phantom Menace writer and director, Star Wars creator: Well, my decision to make Episode I was more or less driven by technology. The first three Star Wars films were designed very, very carefully to be done cheaply. We didn’t go to any big cities, we didn’t have a lot of costumes, we didn’t have a lot of extras. We didn’t have a lot of the things that cost money on a movie like that. So it was really driven by what I could afford. You have to remember, the first film was made for 13 million dollars. Today, that same film costs 300 million dollars. Even in those days, 2001 cost like 25 million dollars. And I think we had more special effects than that did.

With Episode I, I didn’t want to tell a limited story. I had to go into the politics and the bigger issues of the Republic and that sort of thing. I had to go into bigger issues. And in order to do that, I had to come up with a way of doing it, and that’s what digital technology brought me. I had Yoda but he couldn’t fight. I had cities, but I couldn’t build models that big. I had lots and lots of costumes, but I couldn’t afford to make them. So there were a lot of issues that were just practical -- Episode I wasn’t doable for a long time, so I waited until we had the technology to do it.

John Knoll, The Phantom Menace visual effects supervisor: George had mentioned it in one of the company meetings. Back in the mid-‘90s, annually, we’d have a big company meeting, and George would usually address us and sort of tell us what he was thinking. From the time I started there, every year somebody would ask, “Are you ever going to go back and make more Star Wars movies?”

I remember around ’94 or so, in one of the company meetings he said, “Yeah, actually, I think I am. I’m looking at writing stories now.” There was a lot of excitement about that.

Jean Bolte, The Phantom Menace Viewpaint supervisor: We all just sort of clutched our seats. We knew that this was going to be one of the most important projects that we would ever be involved in. Ever. It was the most highly-anticipated thing I can think of. So that was an incredible day.

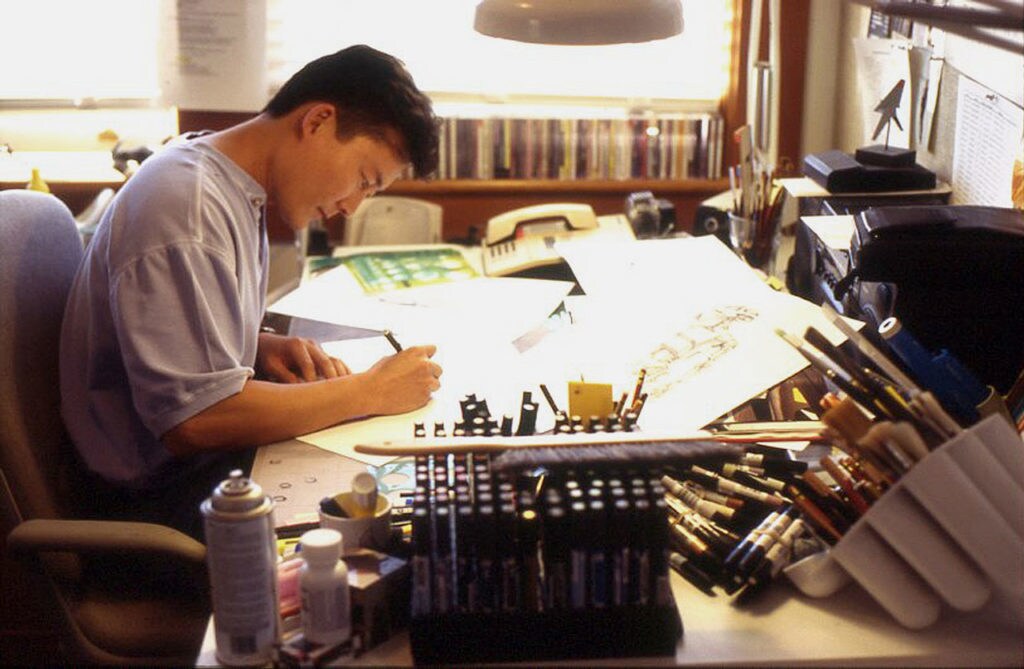

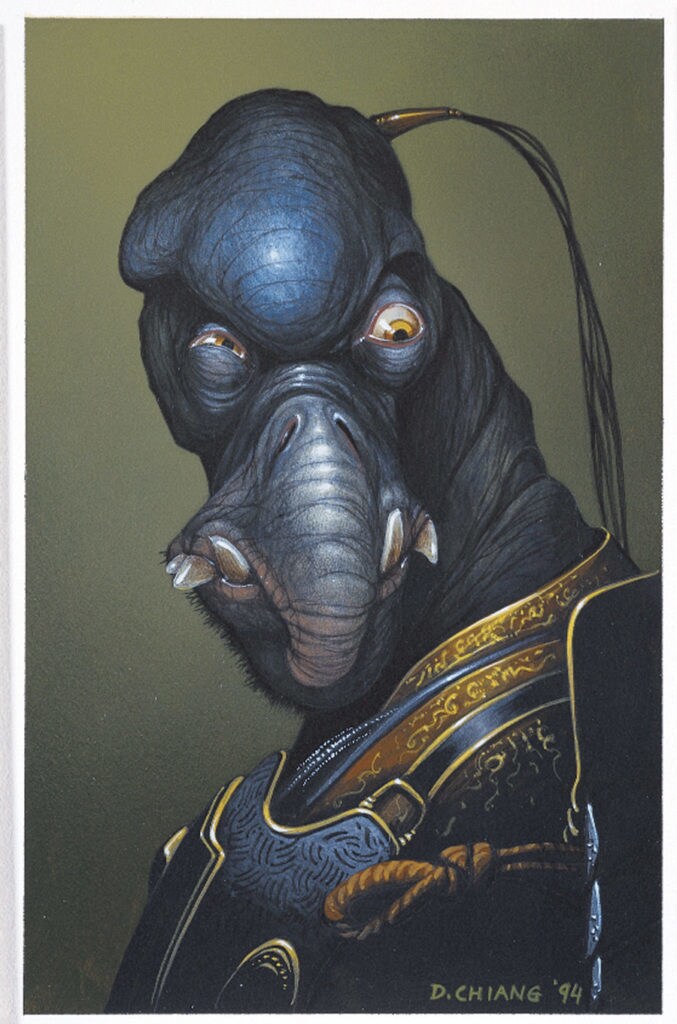

Doug Chiang, The Phantom Menace design director: I came to ILM in February 1989. That’s when I realized that, because I didn’t go to art school, it was really starting to hurt me. That’s when I decided to set a goal: every day for one year I was going to do a piece, work at home every night, with the target that by the end of the week I’ll finish either a hero production painting or a hero concept. I was going to do that for a full year to end up with at least 52 hero pieces to revamp my portfolio.

It worked out really well; the homework I was doing at that time, I was just experimenting with different styles, learning different techniques, pushing the boundaries of my skills. In some ways it was my own art school. I put together my own program. I deliberately gave myself assignments that were uncomfortable to me, and that’s where I learned the most.

My style evolved out of that. Coincidentally, that style was very similar to what Ralph [McQuarrie, legendary concept artist] was doing when he was working with George. What I mean by that is, during that year I was combining old and new, doing different things, adding different cultures, just mixing things up, changing scales. I also loved nature and technology, so I starting to combine those to create something fresh.

So by the end of that year I had a new portfolio, and around that time was when George announced that he was going to make the new films. By that time, I was promoted to creative director at ILM after two years. I thought I would be first in line. I was head of the art department at ILM, this is George’s company, George just announced he was going to make the new movies. Here’s my chance. The irony was that George actually wanted to get fresh talent. He deliberately wanted to look outside the company first. He wanted to cast the talent net worldwide.

So we all submitted our portfolios, and just waited and got in line.

After I submitted, there was a period where I just waited, and then I got a call from [The Phantom Menace producer] Rick McCallum saying, “George really liked your portfolio and would like to meet you.” It blew my mind, because at that time I was just thinking, “I just want to be an artist. I just want to be part of the team.” When I realized that George was actually going to hire me to head up the [Episode I] art department, after the initial shock of that, I was like, “Wow! Can I really do this?”

And the reason he did that was, he saw in my portfolio similarities to his approach to designing Star Wars. And that was mixing genres, combining old and new, all the things that I was doing kind of instinctively on my own. That was the really fortuitous nature of what I was doing. That year of homework really paid off for me because George recognized that, and that’s why I got the job to head up the art department.

Ben Burtt, The Phantom Menace sound designer and co-editor: George called me up to his office and he said he had a sequence that he wanted to try to develop as a videomatic, and this was a year or so before filming. It was the podrace. One of the things that I had specialized in as I was editing for him on The Adventures of Young Indiana Jones was fashioning up action sequences out of stock footage or animation or little models that we would work with ourselves on sticks or planes, and cutting together an action sequence such that it was like a living storyboard. It’s common practice nowadays to do it and there are people who specialize in it. But at that time, I was just left to invent something based on what he was talking about.

And I would pull shots from these various videos and sources, and then piece together a version of the podrace. I probably got a one- or two-page document which described essentially who was in the race and what the outcome was supposed to be. So that was what I started on. I cut together the stock footage. I needed shots of the racers in the pods, so I started by shooting my son Benny just sitting in a big laundry bucket, and blowing a [leaf] blower on his hair, and putting him in front of a screen, like a front-projection screen so it looks like he was zooming along. I took one or two of his friends and I put alien masks on them, just rubber masks, Halloween sort of aliens, and made them into other podracers. Therefore, I had action of them in the cockpit, looking over their shoulders, driving, and so on. I could intercut this with all this other race footage I had lifted from other sources.

I don’t remember the exact timetable, but I came up with maybe a 25-minute long race [Laughs] and it had just about every possible interesting crash and thing I could imagine in it. I would show it to [George] at different points; I’d had some sketchy sound in it so there was some kind of sound for the racers. Then he would add to it. As always, he would give feedback, he would react to the parts of it he liked, and he’d want further development of one idea or another.

We essentially wanted to try all different kinds of gags, how many different ways cars could pass each other, how many different interesting combinations of situations Anakin can get into so that he can cleverly get out of it, and that sort of thing. We just played with this for a long time, months, as an exercise. He wanted to be prepared for shooting with a version of the race that could be shown to everybody in production so he could get an idea of the speed at which things would operate, the kind of angles we wanted.

Trisha Biggar, The Phantom Menace costume designer: It was a great, fantastic thing to be involved in and to be asked to be involved in, particularly when everyone was aware that there were so many people waiting to see what would end up on the screen.

Rob Coleman, The Phantom Menace animation director: I started at ILM in October of ’93. I was the ninth animator at ILM. There were six animators on Jurassic. Then they hired Kyle Balda, who’s [now] actually been directing those Minions films for Illumination. Number eight was David Andrews, and number nine was me. The entire CG department was probably around 45, 50 people total.

My strategy was to work on the smaller films. I was afraid that I was gonna be lost on the bigger films. I wanted to make a mark there. I recognized this as an incredible opportunity. The first uncredited film I worked on, I only did one shot, was Flinstones. Then I worked on things like Star Trek: Generations, Disclosure, Maverick, I did some tests for things like Small Soldiers. I was just a regular animator on Dragonheart, and then James Strauss, who was the animation director, incredibly talented guy, got sick, and they asked me to move up and supervise the animators. So I did do that on Dragonheart, which then got me an opportunity to be the animation supervisor on the first Men in Black.

George wasn’t around in those days. He was taking care of his young kids. But unbeknownst to me, he’d seen the work that we’d done on Dragonheart and then on Men in Black. And I got a call from [then ILM general manager] Jim Morris saying, “George Lucas wants to meet you. We’re considering to put you forward to be the animation director on Episode I. And you need to fly over for a 10-day interview with George in London.” I’m like, “Oh, God.” [Laughs]

Ten days. Two weeks.

Jim Morris has just been an amazing person for me in my life. Great mentor. He’s president of Pixar nowadays, but back then he was running ILM. He coached me on how to talk to George, which was basically to listen and don’t say anything, and then when he asks you a direct question, then you answer him.

This is sort of my nature, and trying to be as well-prepared as possible. I had found a book on early interviews of George Lucas. I think it was published by the [University of Mississippi press]. They were like early Rolling Stone interviews from like, his time doing THX [1138] and American Graffiti. These were all pre-Star Wars films. And in it, I found out that George, for a while, had wanted to be an animator and he was also a big fan of the National Film Board of Canada. Well, I had worked at the NFB. So when it came time, and I’m going to say it was probably day two or day three, to be honest -- I was told to sit behind him in a folding chair and wait for an opportunity, and that he would talk to me when he had time. [Laughs] So he turned to me at one point and said, [in George Lucas voice] “So what’s your story?” I said, “Oh, I’m here from ILM, Jim Morris had asked me to come over and spend some time with you, and I’m an animation supervisor.” He’s like, “Yeah, and what did you do before?” I said, “Well, I started off working at the National Film Board of Canada.” And his eyes went wide, and he was like, “What?” I said, “Yeah, I’m from Canada, and I studied animation with the National Film Board of Canada animators,” which was totally true -- at Concordia University, Montreal. He said, “Here, move your chair up here.” So then we started talking about the NFB and the filmmakers that he admired and I admired.

I think that was just probably the perfect segue into it. I was a fan of Star Wars, but I was not a fanboy. Back then, ILM was super-strict. You were not to be a fanboy, you were not to ask him for his autograph or anything. And I didn’t. I was fine, I wasn’t freaking out to be sitting beside him. I just talked to him, and over the days we chatted more about my approach on how I’d do the work.

It was Rick McCallum who took me aside at the end of the two weeks, walked me outside one of the sound stages, and said, “Okay, you got the job.” [Laughs] I was like, “Oh, my God.” Then… Then I started to freak out. Because it’s whatever that proverb is, “Be careful what you wish for because you just might get it.” Well, suddenly, I had this thing, and then the pressure of it started to really hit me.

Ahmed Best, Jar Jar Binks actor: I was doing a show called Stomp in San Francisco when Robin Gurland, who cast Phantom Menace, came to the show. After the show, I got a phone call that said Robin wanted me to come to the Ranch and audition for Star Wars. At the time I was just like, “Huh?” I didn’t know if there was any Star Wars going on. Everybody kept it really hush-hush, nobody was really talking about it. It was just like a rumor at the time. It was like, “I heard there’s going to be another one.” And there was no way I thought I would ever have a shot at being in it. It just kind of came to me. So I was like, “All right. [Laughs] I’ll audition.”

So I went up to Skywalker [Ranch] one afternoon when I was supposed to be rehearsing. I was in Robin’s little office in the basement of the main house, and she didn’t tell me what I was auditioning for. She just gave me a bunch of different scenarios to go through, improvising different scenarios. I did that, and then she said, “Thank you,” and then two weeks later I get a call to come back, this time for ILM and George. I did that. I came back for my callback, and it was like a callback/screen test. I still didn’t know who the character was or what he looked like, but that’s when the mo-cap happened. I was put in the mo-cap suit, I started moving in the suit, and that was the first time George directed me. I still didn’t know what I was doing, and I didn’t know what was going on, and I didn’t know what motion-capture was. But nobody knew what motion-capture was. This was the first kind of motion-capture-actor test ever. George wanted this to be done but nobody knew it could be. Everybody was really stepping up to the challenge at the time, and I think the one missing piece was how they were going to do it and make Jar Jar feel like a real character, and that he was in this room with all the actors. And they were just like, “Well, let’s get an actor.” That’s when I came in. I did the mo-cap test, and then George said, “Thank you,” and walked out of the room. I was just like, “Okay, that was fun. If this was all there is, at least I had some fun.”

Then, another two weeks go by. I’m getting ready to go to South America with Stomp, and I get this phone call that says, “We want you to be in this new Star Wars movie.” I was 23. I was a child. [Laughs]

George Lucas: You know, all films are personal. Unless you get hired to do something and you just do it. But anything you write, and direct, and have control over is personal. So everything I’ve done has been very personal. You don’t just do movies out of boredom; you do them because you want to do them.

And in that particular case, one of the main driving aspects of the film was the backstory. In doing the first three Star Wars, I had to create a backstory about where everybody came from, what they did, and everything that had happened. When I finished Return of the Jedi, there were a lot of stories that weren’t used. I was basically trying to fill in the gaps with pieces that I had to make a full story.

The original idea for Star Wars was one movie about the tragedy of Darth Vader. But as the story grew, it ended up being three movies and the backstory was never explained. I decided that it would be important to finish it off and do the backstory because things that I thought would be self-evident about the story, the audience didn’t get. Over the 10 years after Return of the Jedi, I realized people misunderstood a lot -- such as where Anakin came from. So it was a way of finishing the whole thing off.

Episode I marked George Lucas’s return to directing -- his first such effort since the original Star Wars in 1977.

George Lucas: Actually, I was looking forward to it because, finally, I was going to get to do something that a lot of the frustration had been taken out of. A lot of the frustration in making movies was technical. Once we went digital, it was so much easier. I could focus on the story and other things.

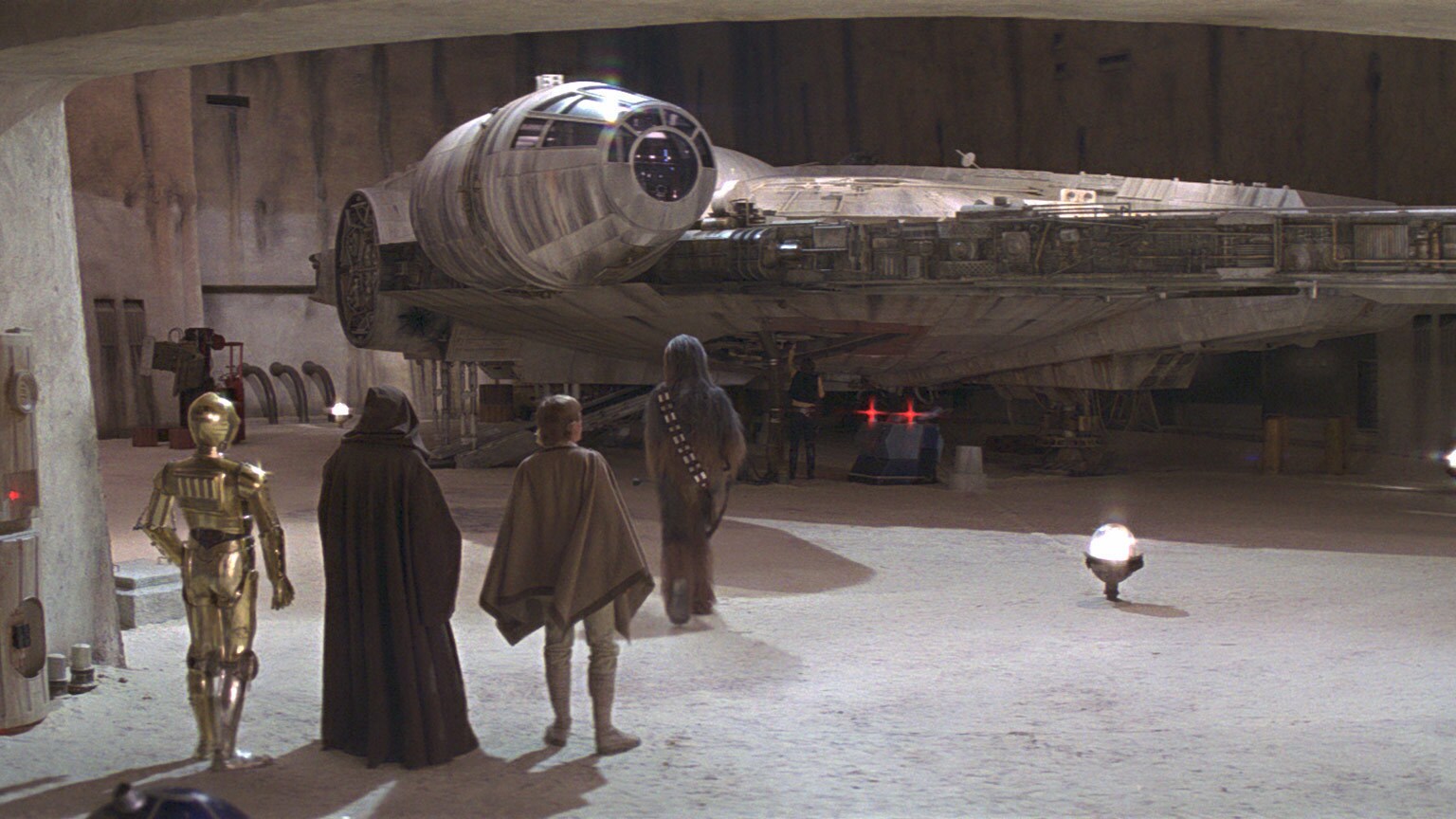

Ben Burtt: I go way back to Episode IV. Back in ’77 when that film came out, and it was a gigantic and pleasant surprise for everybody, nobody was planning for it to be a blockbuster. We just hoped it would be accepted by the niche audience that goes to see fantasy and Ray Harryhausen movies. I remember at the time George saying that we’re going to redo it someday and fix all the problems. I thought, that’s just kinda crazy! [Laughs] You just came out with this incredibly exciting, successful movie that everybody embraced, isn’t it time to move on?

Years later, of course, he kept his vow and we did the Special Editions. That led into the new sets of trilogies. It was an exciting time, actually. Really it was, for me. I looked forward to it when he, as I said, he called me up and talked about this podrace. Basically what he was saying is that we’re doing another movie and he’s inviting me to be part of it.

The story for Episode I, dubbed “The Beginning” in early drafts and through production, would center around Jedi Knights Qui-Gon Jinn and Obi-Wan Kenobi, Queen Amidala, and their accidental discovery of a young slave named Anakin Skywalker. Meanwhile, a seemingly trivial planetary blockade would be the launching point of a secret Sith Lord’s plan to gain control of the Republic.

George Lucas: It’s all based on backstories that I’d written setting up what the Jedi were, setting up what the Sith were, setting up what the Empire was, setting up what the Republic was, and how it all fit together. I spent a lot of time in developing those elements, and what each planet did, and why they did it the way they did. So I had all this material. A lot of the story elements were givens. Early on, it was that Anakin had been more or less created by the midi-chlorians, and that the midi-chlorians had a very powerful relationship to the Whills [from the first draft of Star Wars], and the power of the Whills, and all that. I never really got a chance to explain the Whills part.

So a lot of the story of the prequels, I’d done already. And now I was just having to put it into a script and fill it in, kind of sew up some of the gaps that were in there. I’d already established that all Jedi had a mentor, with Obi-Wan and Luke, and the fact that that was a bigger issue -- that’s the way the Jedi actually worked. But it was also the way that the Sith worked. There’s always the Sith Lord and then the apprentice.

Everybody said, “Oh, well, there was a war between the Jedi and the Sith.” Well, that never happened. That’s just made up by fans or somebody. What really happened is, the Sith ruled the universe for a while, 2,000 years ago. Each Sith has an apprentice, but the problem was, each Sith Lord got to be powerful. And the Sith Lords would try to kill each other because they all wanted to be the most powerful. So in the end they killed each other off, and there wasn’t anything left. So the idea is that when you have a Sith Lord, and he has an apprentice, the apprentice is always trying to recruit somebody to join him -- because he’s not strong enough, usually -- so that he can kill his master.

That’s why I call it a Rule of Two -- there’s only two Sith Lords. There can’t be any more because they kill each other. They’re not smart enough to realize that if they do that, they’re going to wipe themselves out. Which is exactly what they did.

In The Phantom Menace, Palpatine was the one Sith Lord that was left standing. And he went through a few apprentices before he was betrayed. And that really has to do with certain talent and genes that allow you to be better at what you’re doing than other people.

People have a tendency to confuse it -- everybody has the Force. Everybody. You have the good side and you have the bad side. And as Yoda says, if you choose the bad side, it’s easy because you don’t have to do anything. Maybe kill a few people, cheat, lie, steal. Lord it over everybody. But the good side is hard because you have to be compassionate. You have to give of yourself. Whereas the dark side is selfish.

But anyway, there’s a whole matrix of backstory that has never really come out. It’s really just history that I gathered up along the way. So it seemed natural that when I had the technology to actually make the film – for example, I could finally have Yoda be the warrior he was meant to be -- then I would move forward to thinking about how I could make that a movie. Because I had all the backstory, I had basically the three scripts. Or at least the material that was in the three scripts. Then it’s just a matter of doing the details.

The larger story of the prequels -- Palpatine’s ascension to Emperor -- is grounded in history.

George Lucas: The inspiration for Star Wars, one of the very first ideas, was when Richard Nixon tried to change the Constitution so that he could run for a third term. We all knew he was a crook, he was a bad guy, he did terrible things and we sort of chugged along with it. It wasn’t until the impeachment, and really even later than that, that we understood how completely corrupt he was.

But that was the idea, which was, “How does a democracy crumble? How does it die?” When it doesn’t die with a revolution -- it does in some cases -- but not in the world of the ideal democracy, which we thought we had at that time, how does that happen? Would the people vote for it? And yes, they do vote for it, that’s the whole point. There’s an outside threat, and that threat allows the tyrant to take over. And the populace gives up the democratic powers and this guy is suddenly running the show. You end up with the Empire.

That’s what happened with Palpatine, ultimately. Everybody thought he was a nice guy. But he wasn’t. He was a politician and he was ambitious, and he was a Sith Lord, but he didn’t talk about it. And he was plotting to take over the Republic. He wasn’t just a bad guy that ran around killing people.

The thing about Anakin is, Anakin started out as a nice kid. He was kind, and sweet, and lovely, and he was then trained as a Jedi. But the Jedi can’t be selfish. They can love but they can’t love people to the point of possession. You can’t really possess somebody, because people are free. It’s possession that causes a lot of trouble, and that causes people to kill people, and causes people to be bad. Ultimately it has to do with being unwilling to give things up.

The whole basis here is if you’re selfish, if you’re a Sith Lord, you’re greedy. You’re constantly trying to get something. And you’re constantly in fear of not getting it, or, when you get it, you’re in constant fear of losing it. And it’s that fear that takes you to the dark side. It’s that fear of losing what you have or want.

Sometimes it’s ambition, but sometimes, like in the case of Anakin, it was fear of losing his wife. He knew she was going to die. He didn’t quite know how, so he was able to make a pact with a devil that if he could learn how to keep people from dying, he would help the Emperor. And he became a Sith Lord. Once he started saying, “Well, we could take over the galaxy, I could take over from the Emperor, I could have ultimate power,” Padmé saw right through him immediately. She said, “You’re not the person I married. You’re a greedy person.” So that’s ultimately how he fell and he went to the dark side.

And then Luke had the chance to do the same thing. He didn’t do it.

Galactic Design

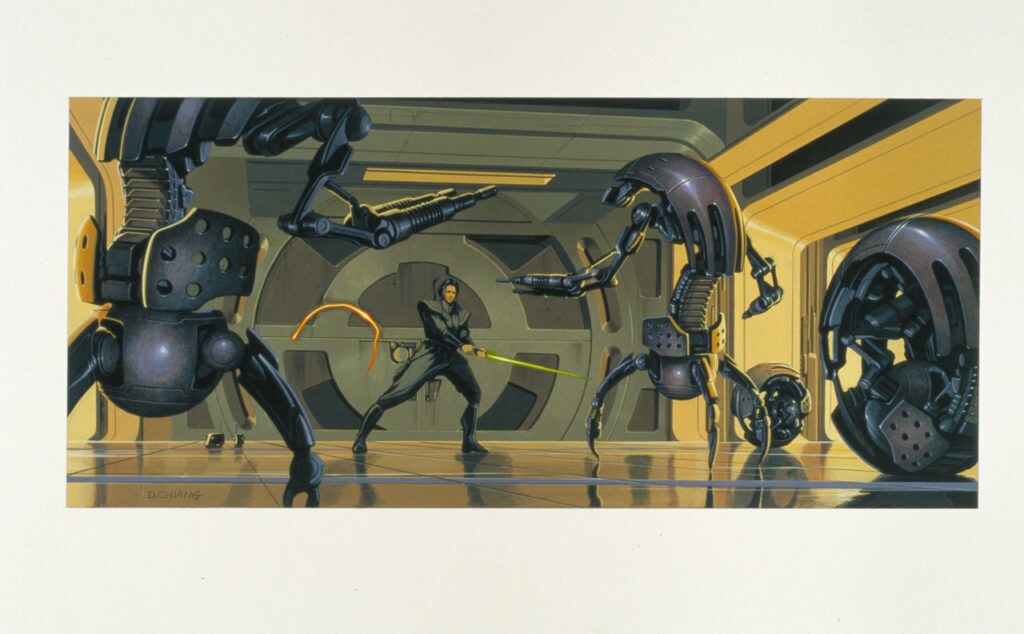

Officially head of the art department, Doug Chiang was in for a surprise when George Lucas briefed him on his ideas regarding the overall look of the prequels.

Doug Chiang: It was terrifying because I’d assumed when I was hired that I was going to do more of the classic designs. I had no idea where George was going to go in terms of design aesthetics. And so that’s why it horrified me, because I’d been doing homework, studying [original Star Wars concept artists] Joe Johnston and Ralph McQuarrie, so that I could do original trilogy designs. And during one of the first meetings, George said, “You know, forget about what you think Star Wars design is. We’re going to start over. We’re basically going back 30 years to lay the foundation for all of that to explain why designs in the original trilogy look the way they do.” And that completely floored me because I wasn’t sure what George meant. I didn’t know stylistically what he wanted to do. It scared me because literally I felt like I’d prepared for the wrong test.

George Lucas: World building is the hard part. There’s so much of it and you have to go down to the smallest detail, the smallest knife and fork and spoon and cup. Besides the people and technology, it’s always the biggest problem, and it’s mostly a problem because it’s time consuming. Even on those original three movies, I had quite a number of designers: Ralph [McQuarrie] and Joe [Johnston], and later on we had probably seven or eight designers. Even then, working full time for two and a half years, you still can’t cover all the territory.

But I did it on the first three Star Wars movies. Each Star Wars movie had three different societies. Three different cultures, three different worlds. And those three worlds were the basis of everything. And then at the same time, those three worlds and those three movies couldn’t be outrageous in terms of the environment because we didn’t have digital technology. We used deserts, and then we used forests. It was hard to find that many different environments to be able to build around. That was one of the problems of going on to the next three, which was I had to come up with worlds, fashion, and craft that were very different. That’s part of the “Where am I, what’s going on, what is this,” part of making a story, which is it’s unique, it’s weird, it’s different. And it’s interesting, it holds your interest.

If you do what a lot of people do, it just becomes generic. It’s just the same old thing. One person I can point to who is great at world building is Jim Cameron. Avatar was brilliant. It’s hard to design worlds and come up with stories and have them operate around it. You have to know the rules on everything. If you don’t play by the rules, then it becomes just a mishmash. If you come up with something new, you have to say what all the rules are about it.

Doug Chiang: The good thing is, that during the whole process, I realized that part of why Star Wars design is so timeless is because George anchors it in a real historical timeline. And when I realized what he was doing with that, we established the timeline for all designs with our design history in the US. It made complete sense then, so that we were going to design the prequels from 1920s and ‘30s aesthetics, where it’s more handcrafted. And then as you segue more toward the original trilogy, design would become more like the manufactured era of the 1970s.

George Lucas: You know, I was in school in ’62, and we had Ford Edsels. So in ’72, there weren’t any left. It was all different. Everything was different. Well, not everything, but all of the design in terms of technology improves.

When you jump 20 years later, to [Episodes] IV, V, and VI, the Empire has taken over, so the technology goes downhill. The Empire has good technology, but what some are forgetting, or don’t know, is that the X-wings and most of the Rebellion’s ships were all sort of junkers. They picked those up at various garage sales from armies that didn’t want them anymore. Rebels, in IV, V, and VI, didn’t have the money. They just had to pick up whatever junkers they could get anywhere because they were rebels. That kind of detail gets lost.

There’s movement in their evolution. You are where you are, and it’s not the same place. You’re not going back to the same movie.

Trisha Biggar: George always said it wasn’t a futuristic film. It was sort of almost like a historical film. So we did a lot of research into all sorts of cultures, peoples, sculptures, woodcrafts, paintings, textiles, anything. Influences could come from anywhere and they did.

Doug Chiang: George surprised me on many levels. One, I didn’t realize how much of an artist he is as far as in artistic vision. His tastes are exquisite in terms of fine art. And the main thing that I really appreciate is, I admired him as a filmmaker and storyteller for sure, but I didn’t know he could get in there and be very critical with design. I thought that was my job, that I was going to present a design and I was going to sell it to George, and he would approve it. That’s basically why I was hired. And it was the other way around! I actually learned so much about design from George because he could critique a design, and he could tell me why it doesn’t work.

It was a fascinating thing for me because sometimes I can get very obsessive about tiny details, things that don’t really matter. And George cut through all of that. One of the most impressive things is that he could do that very quickly at many levels. He had a way of looking at a whole bunch of different images and then really pulling out, very quickly, the handful that he liked. I was always impressed at how he could do that.

I remember asking him once, finally, why and how. His answer was very simple. It was because he could understand those designs very quickly. From a sort of graphic logo silhouette point of view, he could read what that is and he could understand it. And his whole point was, when these designs show up in a movie -- and this is where my three-second rule came about -- the audience is not going to have you there to explain it. They have to understand it quickly. If they don’t, it kind of completely removes you from the moviegoing experience.

That transformed how I approached design because it applies not only to film, it applies to all kinds of other designs as well. Now, when I design, I think of it like, “How do you distill it down to the bare essence?” Because that’s what George wants. He wants to understand it clearly. He wants to make it so that it’s almost like a logo of what the design is, and that’s why if you look at a lot of the original trilogy designs, they’re very simple graphics. A kid could draw them. And that’s the main point, that they have to be that simple so that, even with a little doodle, you’ll understand what it is.

Now with a solid grip on the design approach for The Phantom Menace, Doug Chiang and his team got to work.

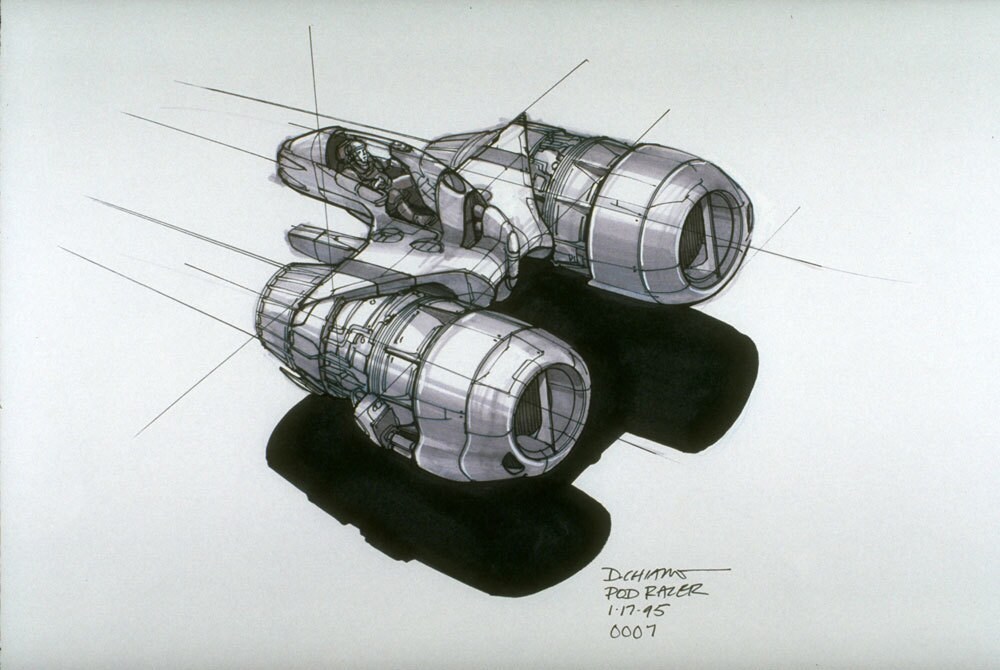

Doug Chiang: There were no scripts when I started work. It was basically just ideas, and he would just throw out things. For instance, the podracer, he said, “I want a new kind of race, and basically take two engines, tether it together, and add a cockpit.” I had no idea what the context was, I didn’t know at that time whether it was going to play a big part in the movie or not.

So a lot of it was just fragments of ideas. I love the process of working with George. As he was writing, we were in there drawing and designing. Sometimes what I drew would inform what he would write, and vice versa. Every week it would change. Sometimes I could spark something with an idea for him, and he would suggest, “Okay, let’s pursue this.” The next week I would show him something new, and I could tell that he thought about it and modified it a little bit in terms of how it fit. And he would push me in a new direction.

It grew very organically that way. I didn’t get the script until, wow, about a year afterwards. At that time, George, I think, deliberately wanted myself and [principal creature designer] Terryl Whitlatch during that first year to just kind of explore. Because he just wanted food for thought. A lot of times I didn’t know exactly what the planets were going to be, how much of a role. I just went in and just designed it.

Jean Bolte: I went up to the Ranch, and I saw Doug Chiang’s artwork -- his storyboards and artwork, there were just rooms with it all on the walls, one wall after another going through and every piece of it was so beautiful.

We take it for granted now, but when you look at something where you see a character who is not possibly going to be a human character, riding an animal that you can’t create in a model shop, in a world that you’ve never imagined before… Seeing that repeatedly, on every single piece of art, and going from such extremes, just so many different worlds that had to be created from nothing -- we had never, ever experienced anything like that. I remember thinking, “I just have to go lie down.” Not only from the sense of how big this thing was, but also, there’s something about when you see that much of Doug Chiang’s work in one place -- it’s an overused word, but it’s awe-inspiring. You really feel that you want to do justice to something that looked that beautiful.

Iain McCaig, The Phantom Menace concept artist: I remember going up to see Doug and Terryl [Whitlatch], and when I walked in, you know, they had been working on it for about a year. So the walls were wallpapered in beautiful creatures and spaceships and machines and environments, and I just thought, “Well, shoot. What am I going to do?” And then I noticed nobody was drawing people. So I said, “Oh, can I do those? Do you mind?” So just because that’s what I draw, and wasn’t what they drew, I got all the main characters. And because I don’t draw them naked all the time, I got all the costumes, too.

Here, Doug Chiang, Iain McCaig, and costume designer Trisha Biggar discuss some of the film’s most iconic designs.

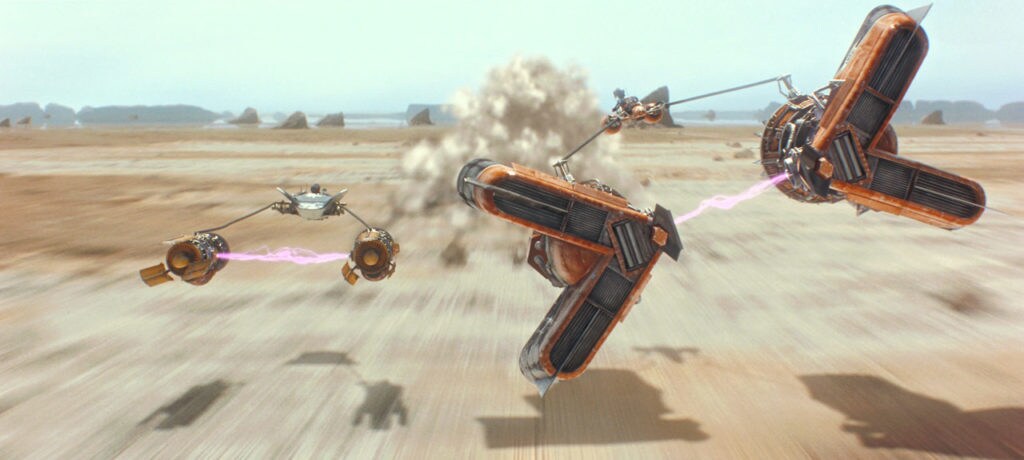

Anakin’s Podracer

Doug Chiang: Anakin’s podracer was really fun. The podracer was one of the first things that I really jumped onto as a design. I liked car racing, I liked the idea of technology, I liked the idea of where he was going with this mess of engines. Initially when I started, I thought way too logically, because I thought, “There’s no way anybody could fly two untethered engines. That’s impossible.” Then I realized that was the whole point and why George wanted that. When he equated it to a horse and chariot, then it made complete sense. The horses are the engines.

And in designing Anakin’s, that was really fun because I chased that for so long. I was trying to put too much logic into it at that time. I wanted it to make sense. “If these are engines, how would they really mechanically work? How would they tie to the cockpit? Where would the fuel tank be?” George just kept saying, “No, no, no.” None of the designs that I was presenting to him worked.

I finally decided to do research and went to the maintenance bay at the San Francisco [International] Airport. Seeing these giant engines stripped of their cowling, hanging in these spaces, I was just awestruck. It was just amazing. That’s when I realized you don’t have to do much; you just take these raw engines and put it out in the desert. It completely worked because it was exactly George’s design philosophy. We were taking something very ordinary and putting it into a new context and creating something new from that.

Once that idea stuck, it was a matter of coming up with different configurations of these engines. That became a real challenge because it was going to be a very kinetic race. George was very keen on making sure that each of the podracers were easy to distinguish and identify.

So for Anakin’s, we wanted to come with an identity that made him stand out. Originally, George wanted Anakin’s to be very generic. He had the cheapest version. He just found an engine, he had a very simple cockpit. It would be the most plain and the most ordinary so he would be distinctly an underdog. Later on George decided that maybe Anakin should have an even smaller engine. That was really nice because then, definitely, it made Anakin an underdog.

I thought, okay, George had described that Anakin was an amazing pilot and that’s how he wins the race. I thought, “How can I visually show that he’s an amazing pilot in a small engine package?” That’s when I decided to give engine flaps so you could actually see Anakin flying and maneuvering around things. That all started to tie together really well in a package of what ended up to be Anakin’s podracer.

The final piece that kind of sealed the deal for the design was that, originally, Anakin’s cockpit was very simple. George decided he wanted it to have a little bit more personality. He asked us to reference the Birdcage Maserati, the 1963 Birdcage. That’s a beautiful car. It looked really great. The idea then was to take the essence, the spirit of that design with the big fairings, and just lop off the underside of it and turn that into a cockpit.

It worked out really well, because that, in combination with the two engines and the flaps, makes for a very iconic design.

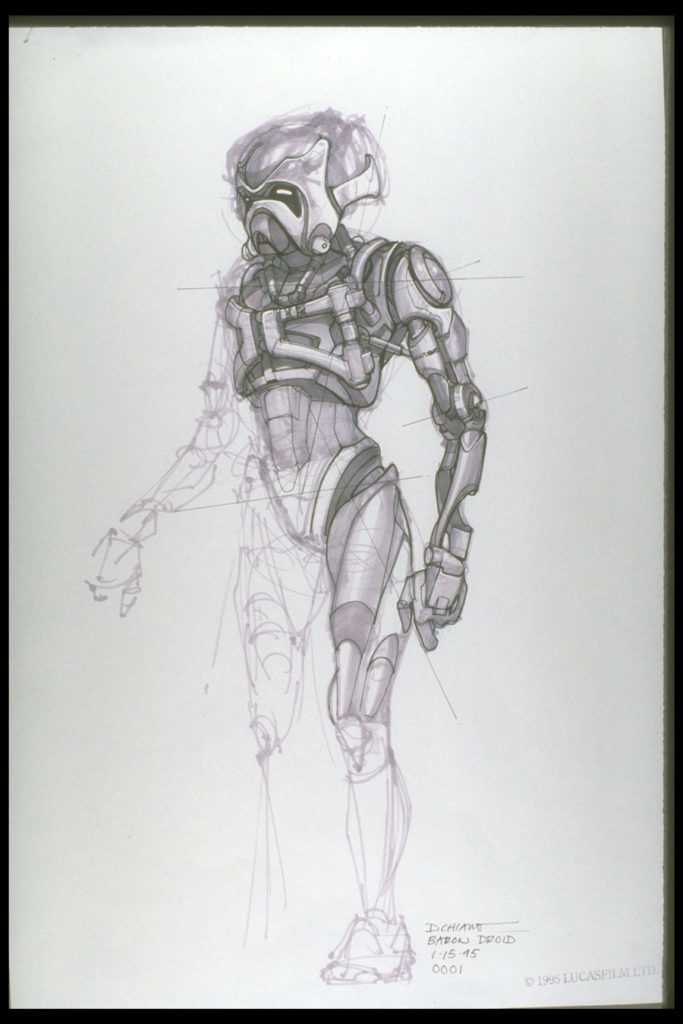

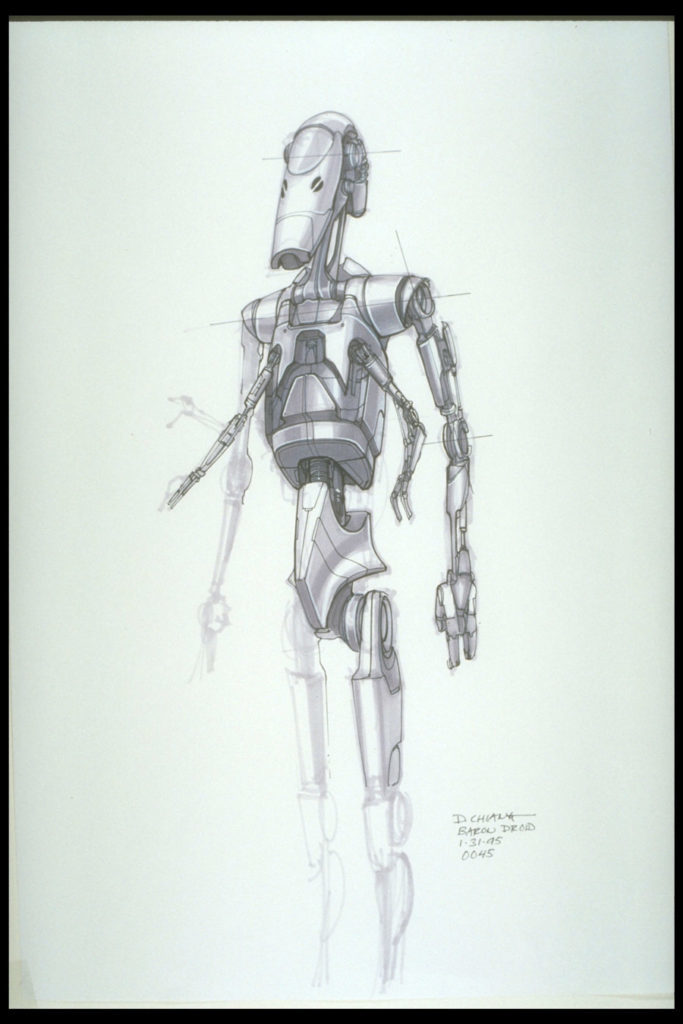

Battle Droid

Doug Chiang: The battle droid was actually the very first drawing that I drew. I think that was my first failure because I took what I heard from George too literally when he described that he wanted a robotic stormtrooper. I drew that -- a guy in a costume, but made it look robotic. It was my first big lesson where I was designing something completely out of thin air, just making it up trying to fit the design brief.

That’s when I realized I should really use research, one of George’s lessons. I found this one photo book on African sculptures and that inspired me to lean toward them, because those sculptures have this wonderful way of stylizing the human form. It was very elegant and almost looked mechanical. I loved the proportions, and that’s where the elongated head came from. When I started to lean toward that, using African sculptures as a foundation for the droid designs, it started to come together.

Slowly, over time, I started to think -- the droids, I wanted them to be distinctly scary. I wanted them to be almost like living skeletons. Originally, they were very thin. Some of my first initial instincts were, I thought, maybe they shouldn’t even make any noise. They should be completely mute. They’re just walking skeletons. That was my first idea; I was taking it too seriously. But that helped inform how I designed. All those things can kind of make for something, because there’s a logic behind the shape language that’s in there.

Naboo N-1 Starfighter

Doug Chiang: The N-1 is one of my favorites. That was a big risk for me because I knew that Naboo had a lot of water and, for some crazy reason, I thought, “Okay, maybe their ships should have an aquatic feel.” That’s why there is a boat-like hull bottom. I was originally thinking that the N-1 would actually land on water, and that’s why it has that. That’s why it doesn’t have landing gear.

But I loved the idea of a really sleek boat form. At that time, I knew George was a racing fan, and he loved F1 cars, and he also liked F1 boats. And the F1 boats were really striking in the sense that they had those lines already. I thought, “Okay, what if we took the look of F1 boats and turned it into a spaceship?” And that’s where the design of the N-1 started to evolve.

So I felt very strongly that I had to make it have the flavor of elegance that George wanted, but also make it functionally practical as well. I took the two pontoons of the F1 boats and turned them into jet engines. I deliberately gave the engines a really long spike, to mirror the tail spike, to give it that real streamlined, fishlike quality. It was a matter of massaging all those details to come up with something.

And that one, I honestly wasn’t sure that it would work, because it was kind of a risky design to begin with. But at the end, it fit all the requirements. It was iconic, it was simple to read, you could tell what it was, and it was fresh. I was very happy that George actually liked it and actually wanted to push it even further by making it a bold color.

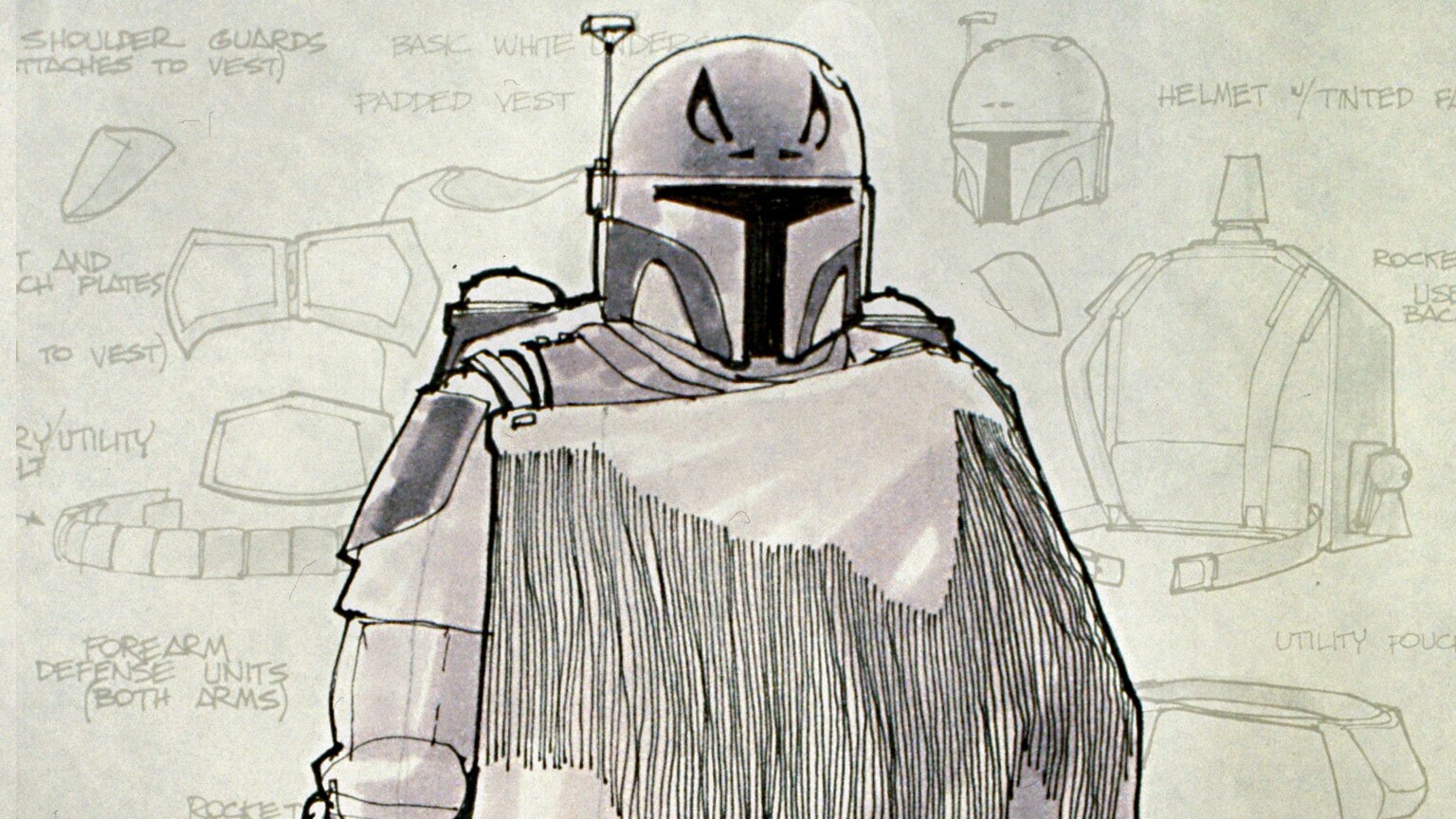

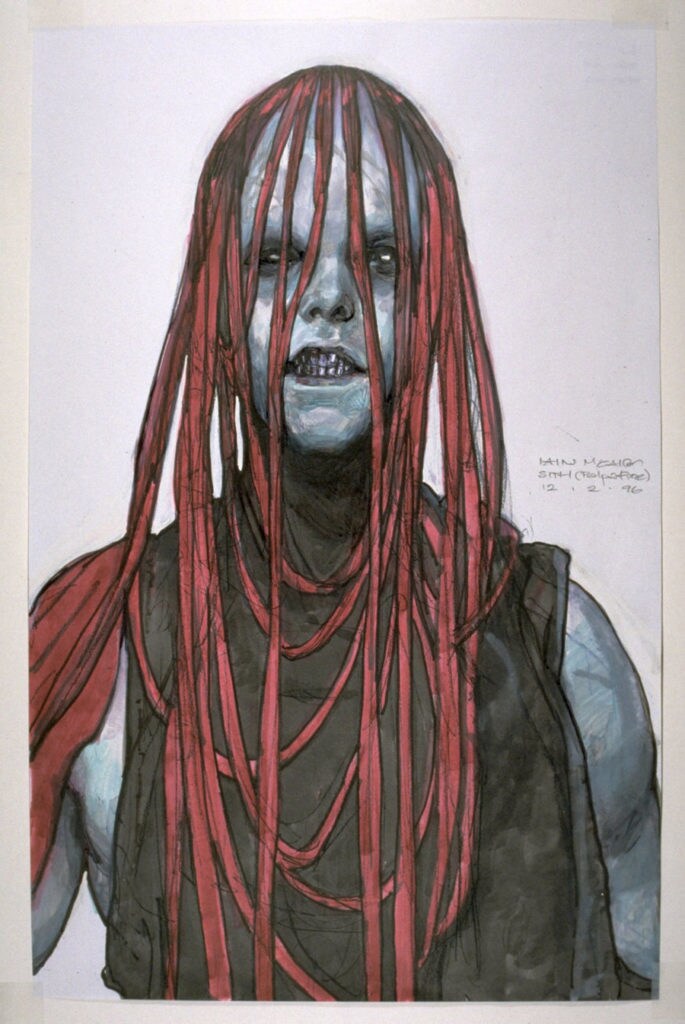

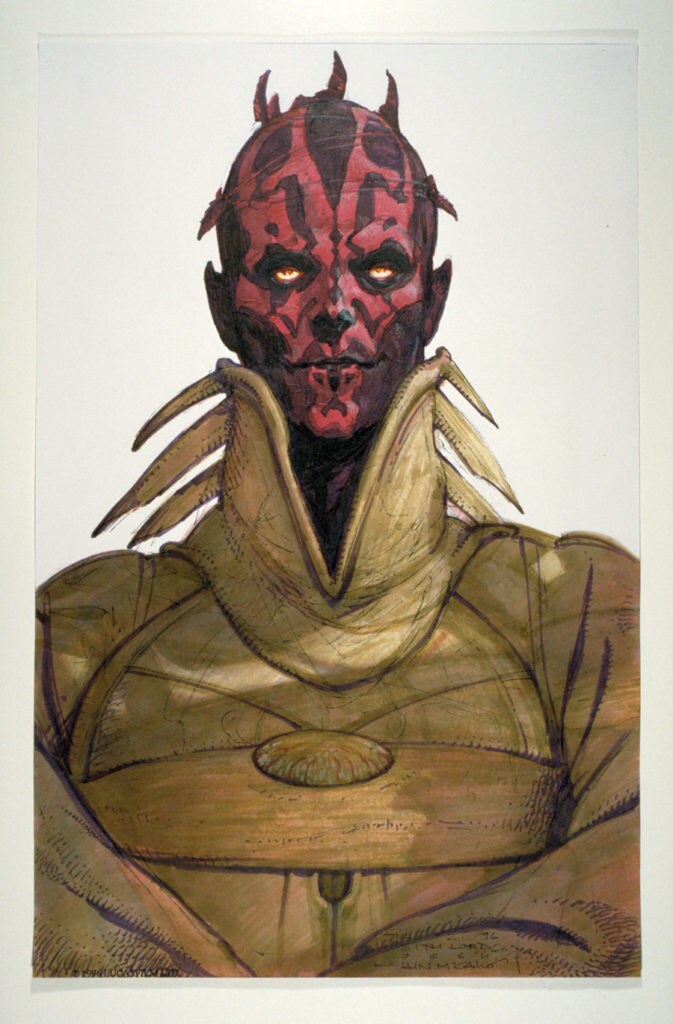

Darth Maul

Iain McCaig: I had a Darth Maul and a Queen Amidala. Darth Maul was the beast and she was the beauty. It was not a love story, so they didn’t get together in this one, but they were both very strong characters, they were both innocent and young, in some ways. So I really couldn’t have designed one without the other. The scarier and gnarlier that Maul got, the more exotic and powerful she got. So they went hand-in-hand for all four years that I was there.

Darth Maul was really, really hard, because all I had as a precedent was Darth Vader. I think, maybe for two years, I was trying to out-helmet Darth Vader, and I almost had a nervous breakdown doing that because you can’t. You absolutely cannot! It’s a perfect design -- you know, skull and a Nazi helmet, it does not get better than that. So finally I decided, “All right, well, heck, take that darn helmet off. Let’s see what’s underneath.”

That’s when I started playing around with the face. I thought there should be some sort of connection with the face underneath and the machinery of the helmet, so I started putting things on the face. Patterns and things, which I intended originally to be circuit boards, or I would carve the face up and let it be light from inside the head that would connect with whatever it was. Just crazy stuff.

For my designs, I never just generically design a person and try to impose a design on it. The design comes from the personality. So I would get everyone in the art department to pose for me, and you just stare at them and say, “What kind of Sith Lord would you be?”

Gavin [Bocquet], the production designer, said, “Don’t make me look fat.” [Laughs] So I put a headdress that covered his chin and then I put a Rorschach pattern on his face, and George seemed to respond to that really well.

And then, and this is several years into it, the script shows up. And Darth Maul is described as “a vision from your worst nightmare.” That was all I needed, because that’s a very clear direction, and I know my worst nightmares.

I drew my worst nightmare, which was that face that’s peering in the window at you late at night, and it’s barely alive. Like a cross between a ghost and a serial killer staring in at you, and it’s raining, and the rain is distorting the face. So I drew that, a stylized version of it, red ribbons instead of rain, and put it in a folder, and at the meeting passed it over to George. George opened it up and went, “Oh, my God,” slammed it shut, handed it back, and said, “Give me your second worst nightmare.”

I tried to figure out what I’d done wrong in my thinking, because you don’t want less, ever. I started thinking, “Star Wars is not real life. It’s mythology.” So I looked for my first best mythological nightmare, and that’s easy, because that’s clowns. I was scared to death of Bozo the Clown as a kid. So I made my big scary clown, and I’d run out of faces to draw, so I used mine. I drew myself into a clown. The patterns became very stylized patterns of the muscles underneath the skin that give expression to the face.

I think that wonderful performance from Ray [Park], put into that makeup, with Nick Dudman’s awesome misunderstanding of my drawing -- because I had given him black feathers, and he thought they were horns -- is what created Darth Maul.

Queen Amidala’s Throne Room Gown

Iain McCaig: First of all, we were only going to have one costume, and I just kept drawing all these costumes. George finally came up and said, “Well, why don’t we do this. We’ll have her change costumes every time we see her.” And then later, “Oh, my God, I’m making a costume drama!” He was shocked himself to realize that.

I remember the only through line I had from the previous films for Padmé was that her mom had that wacky cinnamon-roll hairstyle, which ended up not being so wacky, now that I know it’s from the Hopi Indians, and with a bamboo figure of eight it’s made in a very specific way that they didn’t know when they made the Princess Leia ones, and that’s why it came out looking like cinnamon rolls.

I thought, “Okay, well, if this is her mom, maybe her mom’s hair was even crazier.” Right? And that just made a mark on Princess Leia. Of course, I didn’t know that she wouldn’t have remembered her mom. But that was my through line.

Every time I would start with Natalie Portman, because I had seen her in The Professional. I counted the years from that to this and realized she was exactly the right age for the queen, and I just kept drawing and drawing and drawing her because I loved her face. George came up to me at one point and said, “Do you know this girl?” And I said, “No, sir, but she’s your queen.” And lo and behold, she was cast shortly after! The one and only time I actually got a casting choice put through. But that face is so strong and so beautiful and so innocent and so powerful, it can support any amount of crazy stuff going on around it. So I would dig through history and different cultures, and I would look for crazy hairstyles that I could jump off of. I think there was a fan one that comes from ancient Egypt, there were all kinds of crazy things.

This one, I do remember there was a very powerful upside-down heart shape, and I needed something powerful at the bottom. This design happened right as the idea of “Space Nouveau” took hold. I remember we were searching for that through line for an earlier Star Wars, and I thought, “Well, yeah, it’s handmade, it’s artist-made, so it must be a kind of Space Nouveau.” [Art] Nouveau, as we all know, is inspired by nature and plant forms, and stuff. I used to lie down on the grass at Skywalker Ranch, and draw all the vegetation and come back and turn it into Star Wars costumes. So fresh off of that epiphany, I was doing this costume, and I thought, “Oh, my God, she should have plant forms!” So I put all these seed pods down at the bottom of her costume and colored them up, left them bright for some reason. When George was looking at it, he goes, “Iain, what are those?” You think on your feet, and I went, “Oh, they’re lights, George!” He said, “Oh. Won’t that be kind of heavy, down there at the bottom of the dress?” “Oh, no, they’re very light lights, George!” I quickly called ILM and went, “Help! There are these lights down at the bottom and they’ve gotta be really light and I don’t know how to do this!” Bless their heart, they made one.

Trisha Biggar: The throne room [gown] was probably the most complex of the Episode I costumes for the queen. It looks quite simple in terms of shape; in terms of construction it was quite a complex dress to make. It started off being built onto a frame with sort of a canvas undergarment. The whole thing was almost like an upside-down ice cream cone in shape, with lots of panels being reinforced with a thing called crinoline steel, which kept the shape quite rigid. Originally, I was making the dress in velvet. I changed from that and used a red silk. I think it was between 20 and 30 panels, and it took about two months to make. It was quite a long process, because it had to be really precise. There were hanging panels, and the collar -- there was a Chinese Imperial feel. The other big influence was Art Nouveau, and you can mix influences. It was a favorite of mine.

Now there would be lots of different ways to light it, but then there were less. So it had a great big battery, but you can’t see that, so that was good. [Laughs]

"Well, This is the Future"

Once in production, The Phantom Menace would lean heavily on digital effects and technology, with more visual effects shots than any film in ILM's history.

John Knoll: I think the first time I really got exposed to what was ahead of us -- I suppose the first thing was we read the script. There were, I think, three or four of us: myself, [visual effects supervisor] Dennis Muren, I forget who else was there. I think there were three or four of us, went out to the Ranch. There was one copy of the script [Laughs] and so basically what it is, we sat together in a room, and somebody started and would hand off the page that they had just read to the next person in the line. I don’t know, I was third in line or something, and I would get the pages and read them and hand them on.

It was pretty overwhelming. I had a million questions because you’re reading it written on a page, you can imagine a lot of different ways that that could be executed. That could be a full set, the alien character that’s being discussed, I haven’t seen a design yet so I don’t know whether that’s just a guy in a suit or what. Initially reading through the script it seemed like it was a pretty big and ambitious thing.

Sometime later we had -- and there’s video of this, I think it’s on the making-of video -- we saw the storyboards. George had the art department draw up storyboards for the whole movie. It was 3,600 storyboards, something like that. George walked us through all the storyboards. It wasn’t just telling us what was going on and this is this and that, he was also kind of mixing in what he was thinking about [for] shooting methodology. He had a number of colored highlighters, he had a magenta, a blue, and yellow highlighters, and as he was going down, things that he was going to shoot in front of a blue screen he’d scribble blue where he’d imagine the blue screen would be, and I think yellow was for live-action, and magenta was for CG characters like Jar Jar or battle droids or whatever. He sort of went through that, he went, “Yeah, it’s going to be this,” sort of telling us what was happening in all the frames.

I was used to a situation where almost every show we did there was something that we were doing that was new, that we’d have to develop new tools or new techniques to do, but it’s like almost every storyboard was something that we hadn’t done before or didn’t have tools that could do. I was taking notes the whole time, making note of all the things we were going to have to do in R&D, or new things that would have to be developed to handle doing dense scenes with thousands of characters in them, or robust cloth simulations, or rigid body dynamics. There was a pretty long list of things.

I walked out of that meeting with my head spinning, because it was not only massive in terms of sheer shot number, but in terms of all the new tech that has to be developed to get it done.

Rob Coleman: I remember going back to California and building the team up, and doing the early animations, and as time went on, I started really suffering in terms of insomnia and stress and freaking out, and I knew the world was waiting for this film. After a couple of months, three months, I actually drove up to Skywalker Ranch to resign the job to George. So I booked the time in to see him, and I went in there and I started fumbling and saying all this stuff through three hours of sleep, or whatever I had. He’s like, “What are you talking about?” I said, “Well, just, the world is waiting for this, and the pressure of this, and I’m not sure if I can perform, and…” He goes, “Hey, hey, hey, wait. You’re working for one person. You gotta make one person happy. That’s me, and I’m happy. I think the animation you guys are doing is great.” I said, “Y-you do?” He said, “Yeah. It’s great. It’s my problem to worry about the world, and I’m not even worried about them. We’re making these films for me. You’re making me happy, so you can relax, and you can go back down to ILM and everything will be fine.” I was the happiest guy driving back down Lucas Valley Road. I was like, “Oh, my God!” From that point on, I was fine. I slept like a baby, I was able to do it, I was able to focus on it.

George Lucas: You don’t really start something unless you think you’re right, and think that you’re on the right track and what you’re doing is going to be great. It never occurs to you that it’s not going to work. Otherwise you wouldn’t do it. That’s what keeps people from doing things. So I didn’t worry about that part.

I knew that the process of making a film was very difficult, and most of it was grounded in nineteenth century technology -- or older than that, actually. And it had just reached its limits and there wasn’t anything anyone could do about it. That was especially true in visual effects. And it was through visual effects that I began to realize we had the power and the knowledge to develop something that really would make a big difference. I started that whole process. I wanted to raise my kids, so I retired, but I spent my time building up the company and at the same time developing this digital technology.

Rob Coleman: As reference, I think there were around 200 [effects] shots in Men in Black, and there were 2,000 shots in Phantom Menace.

John Knoll: I’ll give you an example of some of the things we had to develop. I think prior to Episode I, the most complicated CG animation we had ever done was on Mars Attacks!, years before. We had one or two shots that had like 16 or 18 Martians in it, and they all had the little spacesuits and the helmets and their props and all of that. But that nearly brought the whole system down to its knees because having that many rigged characters in a scene at once just was more than the systems could handle at the time.

I was regularly seeing shots where there were 50 battle droids, or a big battle scene where there are two characters fighting in the foreground, but the background had hundreds or thousands of characters back there. This is a whole order of magnitude of higher complexity than we dealt with, so we’re going to need to have systems for managing that level of complexity.

And then a few years before, I think it was maybe ’95, we had done Spawn. There was a number of shots where Spawn’s cape does something magical, and we’d done cloth simulations for that that didn’t look super realistic, and it was fine for the movie because it was kind of stylized. The cape was almost a character in itself. We didn’t have a particularly good or usable cloth simulation system. But looking at the designs of the characters, they’re all wearing clothing. Jar Jar has clothing, and Boss Nass has clothing, and Watto has clothing, and we’re going to have to do digital doubles of the Jedi to do some of stunty things that we can’t shoot for real, and they need to have their cloaks and all of that. We’re going to need to have a good cloth simulation package in there. And we said, all right, we’re going to have to develop that.

And then we had -- there were lots of shots of Jedi cutting through battle droids, so the pieces of the battle droid clatter down onto the ground and that’s hard to animate completely from scratch, and there were so many shots, that, all right, we can’t fake it through that. We need to have a rigid body dynamic system.

These were the things I’d been seeing at SIGGRAPH and technical papers about how to do those believable physical collisions, and we’re going to need a robust rigid body simulation system that’s integrated into our pipeline.

It was just a lot of that kind of stuff. All these things that I knew were technically possible; we didn’t have any tools that did that.

Rob Coleman: Part of my problem was, for months, there was no crowd system, which meant there was no Gungan battle. No ability for my team to animate hundreds of characters back then. It just didn’t exist. I remember there was one line in the script that said something along the lines of “The Gungan army walks out to battle.” That was six months of work -- that one sentence. You were like, “Holy [expletive], how do we do that?” And that was one sentence out of a 100-page script.

Ultimately, it was a matter of acquiring the right tools to accomplish what George Lucas was asking, using the latest versions of software already available, or developing new techniques.

Rob Coleman: We had a database with all the different Gungan walks, runs, throws, falls, fights. We had little vignettes. We’d have Gungans and battle droids, upwards of five of them together in a little cluster, and we’d animate that. And then we could put that cluster into any shot, and we could rotate it, and it wouldn’t look the same to the camera. So we could create a finite number of those and then we could place them, and we’d actually get a fair amount of movement into the shot. We’d just be able to use it over and over again, and we’d put some hero work in the foreground, and the audience would never know.

Jean Bolte: Back then they called it Viewpaint, it was the first software that was developed to paint onto computer graphic models. I was the Viewpaint supervisor. Most people know this, but Viewpaint was a huge leap forward in Jurassic Park. Dennis [Muren] has always acknowledged that. As I have stated publicly, I don’t want to make it sound like I think my job was the most important contribution to computer graphics, but it was a very important one.

The work that we were able to do, because we could paint onto the models, transformed the look of everything. Up until then we’d had The Abyss water tentacle, we had the mercury man in T2, very simple, very rudimentary, you know, the shading on things didn’t allow for very much believability, really. What we were able to do with the paint software, even in the very early, early stages there on Jurassic -- I didn’t work on Jurassic, but I was having a good look at it. They were able to contribute a bump surface and a paint surface to give things the scale pattern, the aging, obviously the color, the different qualities of specularity. And in addition to that, for anything that was hard surface, there’s the aging that comes into making something rusty or dented or scratched.

And when you have that, suddenly a thing has a story. It has a history. In addition to it having the believability, you can introduce the backstory as to, why did it get dented here? Why are the scales roughed up in this area? What kind of creature is this thing? Is it dry? Does it hunt? Is it an apex predator? Is it moist? All of that stuff is the story. So even if you’re making a creature that has never been seen before, you can kind of establish what its niche is in nature, and then contribute all of that to the look of it. The dinosaurs in Jurassic, that was a huge breakthrough to be able to see that.

So the software being very rudimentary still functioned and continued to update. Every project there were things that were written into the software and in our technique and approach that allowed us to get more and more realism.

The Phantom Menace featured several completely digital characters. Jar Jar Binks, played through motion-capture by Ahmed Best, would be the most high-profile, a supporting character that shared screen time with our heroes. Initially, the idea was for Best to perform in a suit and have Jar Jar’s neck and head created digitally, but this proved more costly and labor-intensive than just using a full CG model. Watto, the junk dealer, and Sebulba, Anakin’s rival podracer, were two other completely CG characters that played prominent roles.

Ahmed Best: George wanted a character that was part-Goofy, but very physically aware. He really moved me toward what eventually became the walk. He wanted me to move slower, longer. Jar Jar was taller than I am, so he really wanted Jar Jar’s head to move in a specific way, so that forced me to try to come up with a physicality so that Jar Jar could move in a way that would work once animated. But a lot of it was just a collaboration of movement, me giving George options, and him saying, “Yeah, more like that.” The voice was the same thing. It was just me giving George options, and he was like, “Yeah, do that one. Do that voice.”

George Lucas: I was tired of putting masks on people. I was much more interested in having them be all-digital so you could do more things with them. More freedom.

Ahmed Best: Jar Jar’s character, the movement and the motivation, was really based off of Buster Keaton. George really honed into that aesthetic when it came to me.

Jean Bolte: Casper had a speaking character, Dragonheart, that was a speaking character, but there was something about Jar Jar being a character in this film that was a huge step further. I mean, he had to work in so much of the film in so many different environments. He had to sit there and interact as if he was somebody George had cast and put into a suit.

Ahmed Best: It was great. I loved it. It never really felt like I was this other thing. It felt like we were all actors in the movie working together. This whole idea of me being in the movie or not being in the movie never occurred to all of us while we were shooting. It was never a separate thing and, subsequently, that’s what mo-cap has become now. It’s become actors in the movie, doing the motion, and then animation later building the realized, fantastical look of the character. But the actors are an integral part of the filmmaking and an integral part of the collaboration. And that kind of started with Phantom Menace.

Rob Coleman: I believed in my crew, and I believed that I’d understood what George was looking for from a performance point of view.

Ahmed Best: After principal [photography], I spent probably another year and a half, maybe two years, going back and forth between ILM and New York working out some of the kinks.

That final battle scene with all the Gungans and the droids and the battle tanks, that was me, George, Rob [Coleman], John [Knoll], everybody at ILM, up in San Francisco figuring it out. It was just us in a room, there was nobody else there. I was doing all the motion that Jar Jar did in the final battle scene. George really wanted that to feel like not only just a live-action battle, but he wanted it to have the same physical comedy as a Buster Keaton movie. We worked really hard on that final battle scene.

Jean Bolte: One of the things about this film is that this is what George wanted. He wanted them to have a similar kind of quality to the animatronic characters who also were not necessarily always 100 percent believable. But they had a charm to them, they had a life in them. That was more important than anything. I think Jar Jar has this quality.

Ahmed Best: For me, it was just such a joy to be as creative as I wanted to be because I knew I had so much room. And George was really generous with the amount of room he gave me to bring Jar Jar to life.

Doug Chiang: Watto was completely out of nowhere, and that scared me, because the genesis of Watto was that I did an early trader baron portrait that George really liked. The story of that character changed eventually, but he liked that. One day he came in and said, “Remember that portrait of the trader baron? Take that portrait, let’s put on a body, and add the feet, and add bat wings.” And that was the brief!

It scared me because it didn’t make any sense, and I thought it was going to be a complete cartoony character that people are going to laugh at. I remember we spent weeks and weeks designing it, trying to make it very real, and George kept saying the same thing. And then literally one day I said, “Okay, I’m going to take George exactly at his word, and draw exactly that.” And it worked.

One of my big appreciations for George is that he can push us quite a bit. I learned to trust him that he knows what he wants, and he will then stop us if we’ve gone too far. And right now Watto is one of my favorite characters.

Rob Coleman: The amazing thing about The Phantom Menace, I think, certainly for the ILM animators, is we were moving from putting creatures in scenes to actually being actors in the movie. This is what I was trying to get across to them. The notion of getting up and acting things out. Talking about what’s happening internally inside a character’s head. Do they believe in what they’re saying? What do they want from the scene? Everything you would talk to an actor about I was trying to teach these animators.

Jean Bolte: The main characters, Sebulba, Watto, and Jar Jar, were things that I had painted. Those were great. I mean, Jar Jar, obviously, was an important character. I remember that Doug Chiang [paid] very, very close attention to him. After there was artwork from Doug, and the model, then I would do the texture paint on it, and then Doug Chiang would take a frame render and paint on it. The next morning I’d come in, I’d see what he had done, have a meeting with him, I would incorporate those changes into Jar Jar. That process went on every day for weeks and weeks and weeks.

Rob Coleman: I remember showing [a test of Watto] to George, and he was so excited that he showed him to Frank [Oz], who was doing the actual rubber puppet of Yoda on that first one. And then Frank said to George, “Well, this is the future.” And George was just beaming.

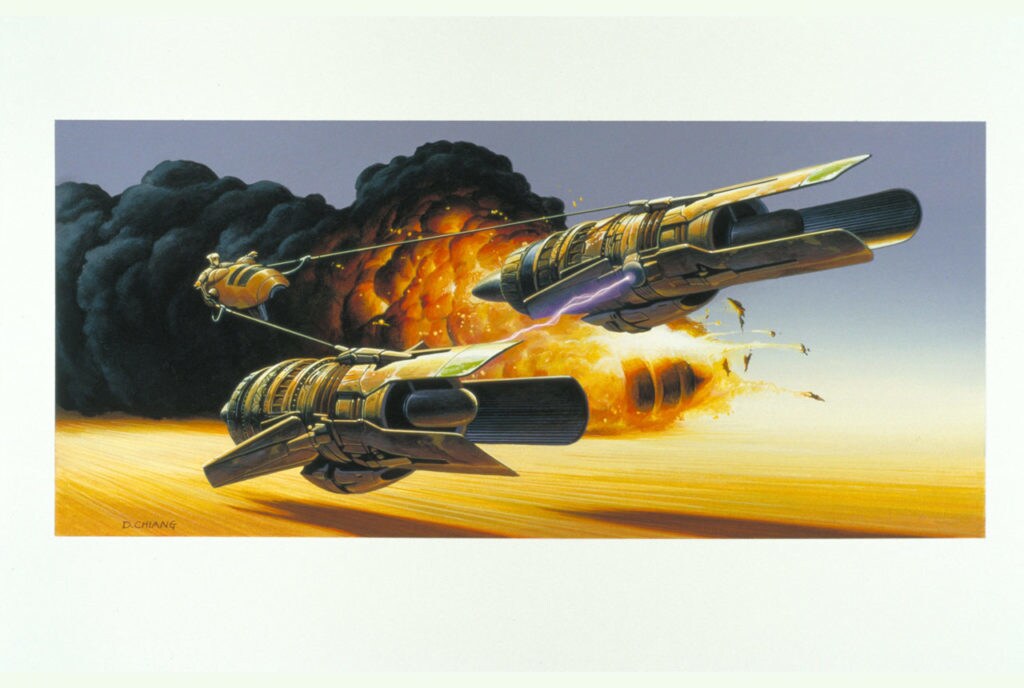

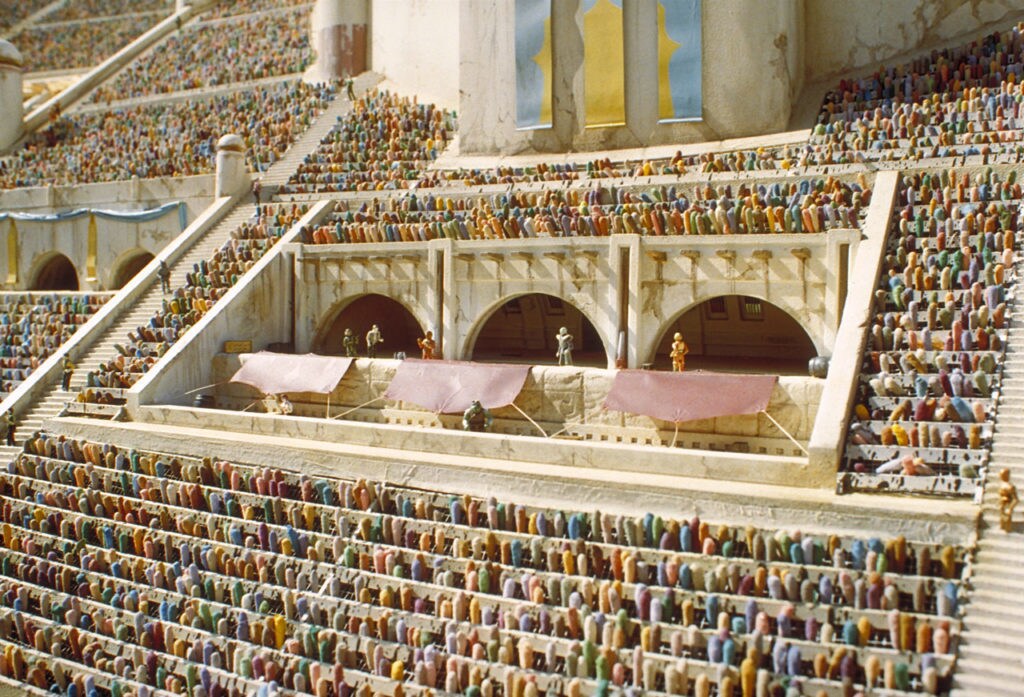

The centerpiece action sequence of the film is the podrace, a fast, furious race between Anakin Skywalker and a smattering of strange aliens, through a course that includes a stadium, caves, rocky terrain, and the occasional Tusken Raider sniper.

John Knoll: I had been playing around with a desktop tool that did two-dimensional physics simulations. It was called Interactive Physics. You could draw 2D shapes and you could have gravity and drag, and you could attach springs or chains to them and let them collide, and kind of do what they do.

Seeing the designs for the podracers, they’re supposed to be suspended on repulsors, like Luke’s speeder, where they just sort of hover, and if you disturb them they have a kind of springy action to them. So they’re supposed to be just kind of hovering there, and then the cables go back to the cockpit. I just kept thinking that they should be, as they’re driving along, bouncing and springing and kind of look like they’re being held up by springs.

I used this Interactive Physics program to build a top down version of a podracer in 2D, where I had two engines and chains that went back to a cockpit. Then I attached thrusts to the engines, and I hooked them together by a spring network. I would jostle them a little bit and they would have this nice secondary springy motion that you would never have the time and patience to animate believably. I just really liked the look of it.

I talked to Habib Zargarpour, my friend that was doing all that [computer animation software] Maya beta testing, and I said I want to try setting something up like this in 3D where we make up a frame and we suspend the pods from springs that attach to the frame. Basically, what we’re going to animate is, we’re going to animate the frame, we’re going to jostle it around, and when we animate the pods we’re basically just animating this frame. The pods are just going to hang from that, and when we move the frame, they’ll kind of bounce around and we’ll get all this really nice secondary motion.

So that’s how the animation system worked, we weren’t actually animating the pods directly. We’re animating this frame that was holding them up.

That was, I think, the first time that we’d done vehicle animation that was all being driven by rigid bodies and dynamic simulation system.

Jean Bolte: I remember the first time I saw the podrace come together on the screen, and I was like, “This is it. This is amazing and it’s a beautiful collaboration.” The model makers and the computer graphics department come before me in the [process]. It’s first artwork, then the model makers get busy, the CG model department gets busy modeling, then it’s passed off to paint. Often it goes back to model and back to paint and back to model.

John Knoll: Yeah, it’s a mixture. Doug and the group had designed this racecourse that had all these very distinctly different-looking regions. It was all pretty deliberate because George wanted you -- if you saw two racers in one particular terrain -- to immediately understand where you were in the racetrack. “Oh, that’s the area right past the stadium,” or “There’s the arches,” or “That’s the area where they get into this narrow canyon.” So if you kind of understood what that racetrack is like, then you cut to this character and you kind of know, “Oh, he’s like 10 seconds behind Anakin because he’s still in the crater field,” and that kind of thing.

We had all these different terrains we had to create, and some of them were more closed in than others. A couple of them, like Beggar’s Canyon, and there was another sort of cave, this stalactite cave, I figured were closed in enough that we could do in miniature.

The podrace stadium was another one where I really felt like we’d get a lot of benefit out of building a miniature of that. Partly I was kinda looking back at how people had done things in the past, and the Ben-Hur stadium from the chariot race, that always really impressed me. Those were done in miniature and they just looked amazing. We’ll build a miniature of that arena, and we’ll shoot all the elements outdoors, and we’ll get that really nice, realistic daytime look.

And then there were other terrains where it was just wide open and we were going at 600 miles an hour, and it seemed like the only way to do it was this CG projection technique. It was a whole mixture of whatever technique would work.

Ben Burtt: I followed through with the podrace from day one to however we ended it. [Laughs] Even in the earliest stages of temporary assemblies of the race I showed George, I always was starting to put sound in. I, of course, had a library to start with of aircraft, and some automobile, cars, and things that had high-speed racing-type sounds that I could manipulate. I would sketch those in a temporary way.

As we went along and the podrace developed, I would go out and record new vehicles, as would [sound designer] Matt Wood and a few others. We’d send them out to races to get drag strips, cars, we did some -- everything from antique biplanes with wires humming on them to running an electric toothbrush up and down a harp string. It wasn’t just restricted to aircraft or anything. We did a lot of cars, a lot of aircraft of different types, and then manipulated other sound effects.

George Lucas: The podrace was the direct result of my lifelong fascination with racing. I thought it would be fun to build really intense race vehicles that were as much sort of chariots as they were anything else, like two horses and a chariot. I took that idea, and plot-wise, it was necessary to get them off the planet. Obviously, you could come up with a million different ways, but I have a tendency to always go toward the racetrack. It was very dynamic. And it’s fun. I love it.

The digital revolution of which The Phantom Menace was part did not stop with effects; it played a big part in the editing of the film and the entire delivery method. Still, the movie was ultimately made utilizing techniques both new and traditional.

George Lucas: I’m not sure where my embrace of technology comes from. All art is technology. Film, or the movies, were the highest point of technology in the art world. You just had to learn a lot, and there’s a lot of technical things to deal with. So that wasn’t the issue as much as it was the fact that I didn’t mind change. And I didn’t mind change because I actually physically worked in it. I worked as an editor, I worked as a cameraman, and I know how difficult it was just working in the medium where you have little splices of film, you can’t find them, when you go to look for something you have to go through reels and reels of film. It takes a long time and it’s very frustrating on lots of levels. Just the whole idea that back in the Kodak days, you’d shoot the film, and then you have to send it in to the drugstore to get it processed, and then bring it back to see what you have, is slow and frustrating. And the whole thing was built on that, whereas if you do it electronically, digitally, you can see what you’re doing as you’re doing it. So you know exactly what you’re doing.

Ben Burtt: Phantom Menace was shot on film. It was the last of the ones shot on film, but it gets transferred to a digital form, then we’re cutting on Avid editing machines. Once you’ve got the image in the digital realm, rather than a physical piece of film, of course then it opens up the door to the amenities of working digitally. You can cut and paste images, and you can duplicate them, and you can flip flop and enlarge them and shrink them, doing all kinds of stuff with a lot of fluidity that you would never have if you were working on a physical film.

George loved that world of manipulation after the fact. You learned working for George that no shot as the camera saw it was final. [Laughs] It could be thought of as just an element for further development.

Jean Bolte: When Jurassic came out, the company offered to train those of us who were interested in making the switch -- they referred to it as “making a switch to computer graphics.” I had no intention whatsoever of making a switch [from the model shop]. What I always wanted to do was to train on this, in the new technology, learn as much as I could about it, but also keep the door open in the model shop. I had to fight kind of hard to make that work. But I think I was fairly successful because during Episode I, I was still able to go back to the model shop and paint maquettes, sort of keep both doors open. I loved that.

John Knoll: To be perfectly frank, I was getting a lot of pressure from George and Rick to do less with miniatures and more with digital techniques. And what George told me, this was, I think, during Episode II or III, he was pushing back on me wanting to do so much with miniatures. He said, “Listen, the future is in computer graphics with these digital techniques, and you’re using miniatures as a crutch. You’re going to have to get better at doing this computer graphics work and expand the palette of things you’re going to be able to do that way. And the way you’re going to get good at it is doing it, so I’m going to kick the crutch out from under you and it’s for your own good. Don’t build so many miniatures. Do this stuff more with digital techniques because you need to be doing that.”

Even though my preference would have been to keep doing what I was doing on Episode I. I look back on a lot of the miniature work we did on Episode I and I think it still looks amazing.

Like Theed city, I think a lot of those shots are completely convincing. You’d never know. And I think the podrace stadium looks pretty good, and the podrace hangar looks really good. And there’s a lot of extensions that I don’t think people even know are extensions that are in the Nemoidian ship, of the corridors and the bridge and all of that. You’d never know.

George Lucas looks back on some of the film’s key scenes.

The opening sequence, in which Obi-Wan Kenobi and Qui-Gon Jinn take on battle droids aboard the Trade Federation ship.

George Lucas: The thing is, in IV, V, and VI, you didn’t really get to see real Jedi in action. To me, that was something that a lot of people would want to see. And of course, the other part is, where are the Jedi at this point? What are they? We’ve never seen one, really, except for Obi-Wan.

The idea was to establish Jedi as what they were, which is sort of peacekeepers who moved through the galaxy to settle disputes. They aren’t policemen, they aren’t soldiers; they’re mafia dons. They come in and sit down with the two different sides and say, “Okay, now we’re going to settle this.”

A lot of people say, “What good is a lightsaber against a tank?” The Jedi weren’t meant to fight wars. That’s the big issue in the prequels. They got drafted into service, which is exactly what Palpatine wanted.

Qui-Gon, Padmé, and Jar Jar come to Anakin’s home and talk around the dinner table; Anakin reveals that he had a dream in which he grows up to become a Jedi and returns to free all the slaves, while Jar Jar snags some fruit with his tongue, and Qui-Gon reveals the real reason they’re on Tatooine.

George Lucas: It’s interesting. It was a hard scene to shoot. Dinner scenes are always the hardest to shoot because of screen direction. It gets complicated. But it was fun, I enjoyed it. It’s a little bit of a domestic scene. There’s a lot of domestic scenes in Star Wars actually, people don’t realize, like the scene with Luke saying he’s going off to the academy, or with Obi-Wan in his home. There’s a number of those.

I liked the idea of having a scene that is not driven by "the phantom menace." It’s driven by family issues and things that they want to do, and about their character. I don’t get to include too many of those because of everything else required in a film like this.

Jar Jar flicking his tongue came into being because he’s a salamander. He does eat flies with his tongue. So the idea of putting that in the scene just seemed like a humorous moment. It’s similar to moments we had for Threepio and the Ewoks, and some of the other more humorous characters.

The final duel between Qui-Gon Jinn, Obi-Wan Kenobi, and Darth Maul.

George Lucas: I wanted to come up with an apprentice for the Emperor who was striking and tough. We hadn’t seen a Sith Lord before, except for Vader, of course. I wanted to convey the idea that Jedi are all very powerful, but they’re also vulnerable -- which is why I wanted to kill Qui-Gon. That is to say, “Hey, these guys aren’t Superman.” These guys are people who are vulnerable, just like every other person.