In composing the score for Solo: A Star Wars Story, John Powell brought together an eclectic mix, blending classic elements from the saga’s original music with his own unique accents.

There’s a professional symphony, complete with orchestral callbacks to John Williams’ legendary compositions and even a new piece contributed by Williams himself.

Powell has also brought in a Bulgarian women’s choir and had the brass section play plastic vuvuzelas. For one piece, he composed a cantina-like tune in the style of post-modern funk complete with lyrics that are all about eating a chicken and sung in (what else?) Huttese.

Powell, an Oscar-nominated composer who has scored over 60 films in his career, recently sat down with StarWars.com to talk about tackling the daunting task of creating the sound of Han Solo’s youth, finding the right theme for the Kessel Run creature, and working alongside the father of Star Wars scores. (Spoiler warning: This story contains some details and plot points from Solo: A Star Wars Story.)

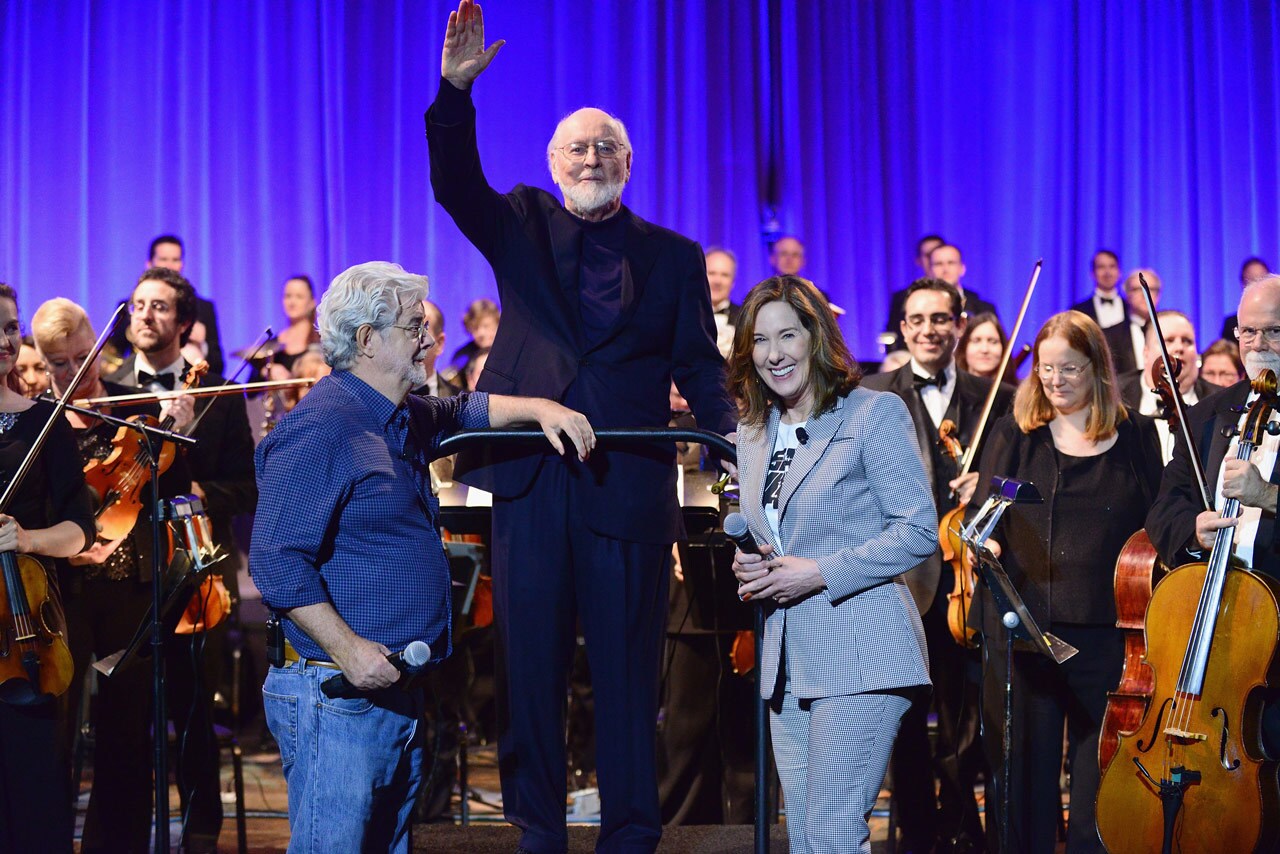

The great John Williams

While Powell was the lead composer for the score, early on he learned that Williams would be contributing a piece, “The Adventures of Han.” Working alongside the man who created the unique sound of the original trilogies and has composed the score of every Star Wars saga film was daunting in itself.

“A mixture of humbling and frightening. He’s annoyingly human,” Powell says with a laugh, “but he’s slightly super-humanly talented. He was very kind. It was like getting your Master’s, going back to college and, you know, realizing there was so much stuff I didn’t know….There’s a level of hero worship that you have to get over.”

Williams made the work look effortless, Powell says, a testament to his legendary status. “I mean his compositional abilities…they have a level of mastery that just doesn’t exist really anymore,” Powell says. “I’d have to start looking at people who come from the 19th century to find the same kind of level. I grew up loving Brahms and Sibelius and Tchaikovsky, and when I look at his compositional abilities, it’s closer to that than anybody else I’ve ever met before.”

Early on in the scoring process, the pair collaborated with the film’s director, editors, and producers to incorporate Williams’ new theme into the score. “He invited me over to his house and at the piano, he played me a theme with two parts; a hero tune being the A section plus a searching B section. I loved them both, obviously,” Powell says. “And then when he felt confident that everyone was happy, we gave him a bit of time and he took that theme and he came up with some more complete versions for the orchestra.” Williams’ contributions of about half a dozen short pieces for the film helped set the tone and create the foundation for the overall score. “Once John had written his stuff, it all made a lot more sense and I really felt like we’d figured out the puzzle,” Powell says. “The searching theme, which I ended up using in the opening titles, was just a one and a half or two-minute suite that he did. So with all of this done, I programmed all of this material into the sequencer, because that’s how I write and we not only used that where it worked but I also took the themes and I developed them in different ways for other sections that he hadn’t scored….They’re woven in and out of the fabric of the whole score.”

Callbacks and new notes

Powell borrowed other elements of Williams’ earlier work in key moments and scenes, harking back to the original title theme as a nod to Han’s destiny, in moments where it was clear his choices in Solo were leading him on the path to that fateful trip to Tatooine.

“One of the themes that I think Ron [Howard] really wanted to get was youth,” Powell says. “You know, try and really make an impression of a youthful, rough, reluctant hero. We know him as the grumpy, old, reluctant hero. He’s still got the bloom of youth, he’s got more optimism than perhaps he had in the movies we know. In those 10 years, those very incredibly important 10 years that we’ve all gone through when we all grow up, what is going to happen to him that makes him more cynical? Basically, I’m always trying to create music that sounded, in a way, less formed and less serious than the music we know for A New Hope and that had this slightly younger, more unrefined feeling to it.”

And although Solo is a dynamic part of the greater Star Wars universe, “the film is different. It’s very different from the other Star Wars,” Powell says. “It doesn’t have the Force in it. It’s not so much about the Rebellion, albeit there’s a proto-Rebellion kind of starting up, so it was a question of just finding, you know, a way to integrate the material that the film needed.” As the Falcon artfully dodges carbonbergs in the Kessel Run, Powell dropped in scoring from another daring escape from the Empire through an asteroid field. “It was based on the visuals in it all,” Powell says. “The way the Falcon’s flying through the carbonbergs in this film, it really did remind me of how they’d been moving in the asteroid field scene in Empire Strikes Back.”

It was also important to make the score his own. Powell grew up listening to orchestral classics before discovering rock icons like Queen, Thin Lizzy, and Bruce Springsteen. As he matured, his tastes expanded to include an eclectic blend of Björk, Massive Attack, Sweet Honey and the Rock, and more recently the Punch Brothers, and Parno Graszt. “I think they’re Romanian, like crazy punk gypsy stuff,” Powell says of the latter. And, somewhat serendipitously, “an awful lot of Childish Gambino’s last album,” Lando actor Donald Glover’s musical alter ego, Powell says. “That wasn’t deliberate at all. It was just an accident. He’s just an incredible musician.”

His personal tastes and professional history all come together to inform the sound he brings to the Solo film. “I can’t help but it be a bit different,” Powell says. “Even though I’ve been forever influenced by John Williams and that original music, I’m not really quite equipped to sound exactly like John. I have my own strange ways of doing things and they make everything sound like me, perhaps. So it was a trick of trying to transition carefully to…try and honor the style. When I’m going for big action scenes, I wouldn’t quite put them together the way that John would, but hopefully you can definitely hear the influence there.”

‘A ferocity of femininity’

The haunting sound of the Savareen stand-off is at once new and exciting yet somehow familiar. Powell heralds the arrival of Enfys Nest with the forceful sound of a Bulgarian women’s choir.

“You first hear them when Enfys arrives on the train,” Powell says. “I was trying to find something that was both exotic and unusual, that sounded like something else: another world had arrived, another style had arrived. I’d always loved John’s choral writing in The Phantom Menace. This was my way of thinking, this could be the solution to this particular scene where I can establish this very different sounding choral sound, but it harkens back to John’s style….I was trying to basically get a ferocity of femininity. I was trying to find a very powerful female sound. It was a little dangerous because, obviously, we didn’t want to give away Enfys’s true nature.”

Powell knew early on that no standard women’s choir would quite do to embody the fierce warrior’s theme. “Everything else in the orchestration was incredibly aggressive. I think if I just used a normal women’s choir, it wouldn’t have worked. It’s this particular sound that they have in Bulgaria where they don’t sing vibrato and it’s a real aggression.”

Some early listeners actually mistook the singers for a group of children. “Well, I’d be very frightened if there were children that sounded like that,” Powell says with a laugh. “That style of music, it’s normally used very beautifully. But there’s an aggressive sound to it, so it gave me a very useful kind of tool to change the movement and…at the beginning, to frighten you, and at the end when they take over. It seemed to work.”

The voice of a space monster

While scoring the Kessel Run sequence, Powell had to craft just the right accompaniment to match the fevered pace of the action on-screen. The composition is one of many that folds in callbacks to the cinematic history of Star Wars with nods including the familiar strains of the “Imperial March.”

“That whole first half of it [“Reminiscence Therapy”], before the monster turns up, is lots of references to the other movies,” Powell says. “As the Falcon does amazing tricks, and, you know, using old material, new material from John, and original material from me.” As the escape got more desperate, and the ticking time-bomb inside the Falcon threatened to make for a very short ride, the score gets more frenetic. “I needed more craziness. How do you build crazy on top of crazy?” Powell asks, adding with a laugh. “It was hard to top, hard to keep getting madder. It just got faster and higher and more difficult for the orchestra until it was virtually unplayable by the end of it, really. I don’t know how they played it. It was a fun sequence to do, it was one of the last ones we did because it wasn’t completed because there were so many visual effects in the process.”

One of the challenges came in the form of the fearsome summa-verminoth, the massive tentacled creature that chomps on the Falcon’s escape pod before getting torn apart in the gravity well. Ron Howard and the producers had one specific request: “[They] kept asking for us to try to feel a little bit sorry for the space monster,” Powell says. He tried to find a voice to represent the beast in the score, but no traditional instrument would quite do. “I was in London with the brass section -- literally, probably the finest players in the world, they were incredible.” While recording in the famed Abbey Road Studios, Powell gifted them with new instruments. “I bought them all vuvuzelas, which are those kind of cheap plastic horns that people used famously at the South African World Cup. It’s a raucous noise, a very unpleasant raucous noise. And I just thought, I need to see what all these incredibly fine players who have hundreds of thousands of dollars-worth of instruments normally would sound like on a $3 big tube.”

The sound is akin to a “really horrible honking noise,” Powell says. “That’s kind of a little bit of a signature sound for the space monster. It’s a mixture of a cry that is supposed to represent some kind of loneliness, fear and desperation.”

‘Chicken’ for dinner

Powell didn’t take inspiration from‘70s and ‘80s pop culture and musical influences that helped inspire the costume design and other elements, opting instead for the timelessness of a symphony, but there was one number where he channeled galactic post-modern lounge funk.

For the song “Chicken in the Pot,” Powell wrote what is essentially Solo’s cantina number: a funky party song to be performed aboard Dryden's yacht. The name, Powell explains, was inspired by the early concept art he reviewed for the scene. “It came from the original drawings that I was given over a year ago, before they shot that scene,” Powell says. “I had to try to come up with something to film to and all I saw was this kind of little drawing. It really looked like a chicken to me. In a pot. So I just wrote some words in English, which was basically about how the singer was going to eat the chicken and then we translated that into Huttese….It’s a very strange piece, but it’s a strange galaxy and, you know, it’s an odd group of people at that party.

“You try to make it as unusual as the rest of the design: the alien designs and the production designs, the makeup. You try and match the strangeness of that but with a recognizable sort of sense of what it is. In this case, it’s basically lounge singers doing their act.”

Now that Solo is in theaters, Powell can appreciate his part and the film overall from the perspective of fan and viewer. At the world premiere in Los Angeles “there were so many fans. They were taking gasps here and there and really laughing at things and having fun. Generally, I’ve found that everybody has really loved the movie, which is always nice because everybody’s trying to make the best movie we possibly can and I loved the script when I first read it.”

But despite playing such an integral role in the final product, the film still retained moments of surprise and discovery, Powell says. “I visited the set a year ago when Ron was in London shooting [on] this giant rig that they had for doing the train scene. It’s a giant moving rig, so they’re stumbling, there’s lots of green screen around it. It just looks crazily not like anything in particular. And then as I worked on the film and the shots came in and that scene would change, it still looked incredibly rough. You’d see these images of just a rig, a just about roughly recognizable bit of train, possibly, but not much else.

“And then we turned up to the premiere and I’d spent weeks and weeks and weeks on that scene and I looked at it and the first thing I thought was, ‘I wonder where they shot this.’ Now, that’s madness, I knew that they shot it at Pinewood [Studios], I knew there was no place that this was shot, but it looked so absolutely perfect. Even I was completely transfixed. It looked absolutely real….So that’s a wonderful moment, when you realize that you’ve been part of creating a completely absorbing and believable world. That’s a great feeling.”

Solo: A Star Wars Story arrives on Digital and Movies Anywhere on September 14 and on Blu-ray 4K Ultra HD, Blu-ray, DVD, and On-Demand on September 25.

Associate Editor Kristin Baver is a writer and all-around sci-fi nerd who always has just one more question in an inexhaustible list of curiosities. Sometimes she blurts out “It’s a trap!” even when it’s not. Do you know a fan who’s most impressive? Hop on Twitter and tell @KristinBaver all about them!