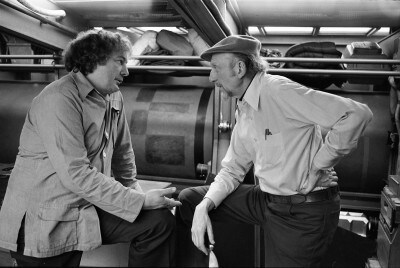

He was a bear of a man. Big men -- gaffers and grips -- worked for him and did so with the greatest of affection. Broad and full were his shoulders, carried high, pushed tight against the neck. With his barrel-chest, he squeezed his words through the back of his throat and nostrils, as is the manner of those suburban London lads that communicates controlled authority, experienced professionalism. In tributes after he died in 2005 at the age of 74, he was lauded as the finest and most respected first assistant director in the world. Around the time he AD’d Return of the Jedi, he reckoned he had done 478 films. In a previous post, I characterized him as a great who orchestrated symphonies out of chaos. This time, I’m going as far as to say that David Tomblin was the greatest first assistant ever.

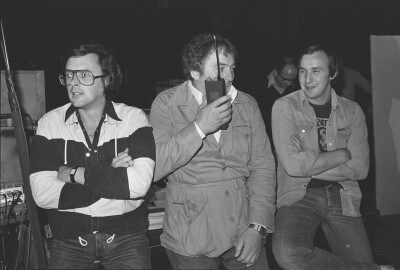

I first met him in September 1976, when I reported for duty in The Netherlands to play Robert Redford’s chaplain in A Bridge Too Far. Big Dave was Richard Attenborough’s first assistant for this epic war film. Most of it was shot on location with AD responsibilities at times involving coordination of thousands of extras, scores of actors, vehicles, planes, boats, and camera crews. Not to mention liaison with local Dutch authorities, e.g., to arrange for stopping the incessant commercial barge traffic on the Waal River to shoot (many times from all angles) Redford’s amphibious assault on Nijmegen Bridge. The day I arrived, Dave and his able assistants, Steve Lanning and Roy Button -- whom he later brought to Star Wars -- were choreographing with their Motorola walkie-talkies the shooting of the parachute drop. It required his coordinating 28 camera crews, a host of Lancaster and Dakota aircraft, hundreds of de-planing parachutists, and hundreds more (Dutch Army conscripts) on the ground. Monumentally spectacular, to be sure. These enormously expensive, complicated, and sometimes diplomatically tricky -- and dangerous -- shoots also had to be right the first time.

David Tomblin was a film man. He was born in 1931, just down the road from the Elstree Studios in Borehamwood. He started working in films as a teenager in the '40s before he did his National Service as a Royal Marine. Having what those in the forces call military bearing, he had especially good working relationships with his crew, union men -- stunt coordinators, special effects technicians, electrics, armorers -- in the technical areas that demand realism, attention to detail, extreme care. These fields are particularly dangerous. Lives are at stake.

Big Dave commanded respect. Notably that respect also came from his directors, like “Dickie” Attenborough, who himself had been a military man. In World War II, Lord Attenborough had proudly served as a Royal Air Force air-gunner cameraman, flying missions over Europe, shooting film from the tail turret of a Lancaster bomber. Attenborough later used Tomblin as his first AD for his crowning achievement Gandhi. Big Dave famously AD’d the funeral scene that involved hundreds of thousands of extras.

I worked with Dave -- or rather, I should say, for Dave -- on three big-budget films: A Bridge Too Far, Superman II, and The Empire Strikes Back. For two months just prior to my time on Empire, I worked on location in Spain with Steve Lanning on a fourth—Cuba, the low-budget Sean Connery film directed by Richard Lester of Beatles fame. So I arrived on the Elstree set as part of the family, so to speak, someone who was prepared and willing to do anything for Dave.

And Dave gave back. An unaffected man, he was absolutely secure in himself and who he was. Taking from his career the understanding that great filmmaking is a collaborative art, he had a bottom-up view of how one got things done. Often I witnessed how he maintained morale on the set by ensuring that all hands appreciated how everyone contributes -- right down to the tea lady. Not that he suffered fools -- far from it -- but Dave took the attitude that if you did your job without complaint, with the right attention and professionalism, he wanted you on his team. And moreover, he would look after you. Many times, I’ve heard similar sentiments from others who worked with him on Star Wars, notably Jack McKenzie (Lt. Cal Alder), Allan Harris (Bossk), and Chris Parsons (4-LOM).

But Dave was more than a technician’s technician. He was also an artist. He had the range of creative intellect and experience to bridge the technical, artistic, and business aspects of filmmaking. From his conversations on the set with me in 1979, I maintain that his proudest achievement to that time had come through his friendship and professional association with Patrick McGoohan, famed star of the TV series The Prisoner. Dave and Pat were partners of Everyman Films Ltd., the London production house that did the series for Lew Grade’s independent commercial television company. Dave was the series’ co-creator and at various times served as producer, director and writer. (He and McGoohan had worked on its predecessor, Danger Man, that Grade’s independent TV company first aired in 1960 and ran to 1968.) Ever since broadcast of its 17 episodes in 1967 and 1968, The Prisoner has inspired a cult following to this day. A fan organization called Six of One still gathers in Portmeirion, Wales, yearly and has thousands of members worldwide. Anyone familiar with the series will recognize how some interior sets are similar to those in Star Wars. Thanks to his decade of work with McGoohan, he was already well experienced in resolving technical challenges while shooting. Together with his big-budget film credits of the '70s, Dave brought considerable skills and talents honed on The Prisoner to George Lucas and Star Wars. While he did not come aboard until Empire, Dave also AD’d Return of the Jedi and The Phantom Menace and with Irvin Kershner’s recommendation also supported Steven Spielberg for all three Indiana Jones films.

I recall on the set of Empire during some rare downtime talking with him about The Prisoner and our careers. Somehow he knew I had written a screenplay about the Soho strip clubs that the London-based American producer Elliott Kastner was interested in optioning. Kastner had just agreed to fund some location research involving my going to New Orleans with another London-based American producer, Patricia Casey, to re-locate the story line in the French Quarter. I would leave as soon as I finished shooting at Elstree. On my last day on the set, I went to Dave to say goodbye and shake his hand. I found him talking to a couple of suits I didn’t recognize. In any case, I was focused on Dave, and when done I was about to turn and go, but he stopped me. Nodding to the pair of suits to his left, he counseled, “Don’t forget to shake hands with the money.” To paraphrase Paul Newman in Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, “Who were those guys?” For the life of me, I can’t remember. Point is, that was Dave, giving back, helping a mate get a hand up. I’ll never forget him.

John appeared as Dak, Luke Skywalker's back-seater in the Battle of Hoth in The Empire Strikes Back. He also appeared in the film substituting for Jeremy Bulloch as Boba Fett on Bespin, when Boba utters his famous line to Darth Vader, "He's no good to me dead." Follow him on Twitter @tapcaf.