It took 16 years to get an answer, but Manuelito Wheeler never gave up hope.

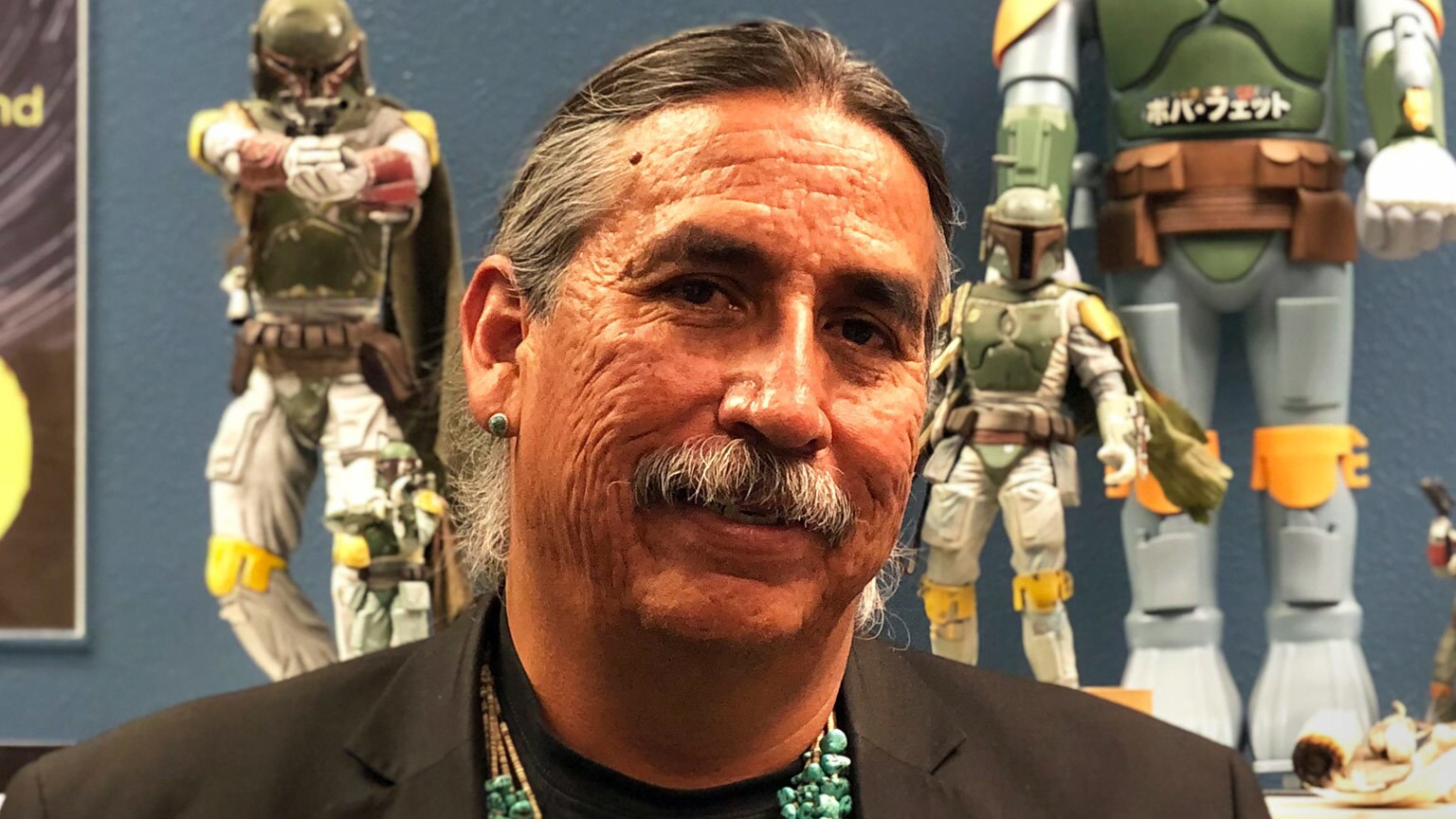

In 1996, Wheeler worked as the creative director at the Herd Museum in Phoenix, Arizona. His wife, Jennifer, had experience teaching the Navajo language from the elementary school level all the way up to university; she also held a PhD in English. Both Navajo, they made it their lives’ ambition to tell the stories of their heritage and history. “We made an awesome team,” Manny, as he’s informally known, tells StarWars.com.

The Navajo language, and keeping it alive, was a big topic of discussion at home. Navajo wasn’t spoken in pop culture or even in everyday city life within the Navajo Nation (a reservation of federally protected land including portions of New Mexico, Arizona, Utah, and now Colorado), and Wheeler and his wife both worried about the language dying out. But Manny had an idea. “'I wonder if putting a movie in Navajo would ever be a reality?’” he remembers saying. They talked about it on and off, until one day, Wheeler, a longtime Star Wars fan, bought a copy of the script for Star Wars: A New Hope. “I took it to my wife and said, ‘Can you translate this? Translate the first five pages of the script.’ I thought it was going to come the next day, or in a few days. ‘Whenever you can get to it, that would be good.’ But she came back in like, 20 minutes. ‘Here’s the script.’ That really blew me away and made me think it could be possible.”

And that’s when Wheeler wrote his first email to Lucasfilm. Though he’d have to exhibit Jedi-like patience, the house that Skywalker built would eventually respond.

The answer comes

For years, Wheeler would email and call Lucasfilm. Not every day, but sporadically, just to see if he could find someone interested in making a Navajo-language dub of A New Hope happen. “I wasn’t kidding myself. This was like, Lucasfilm,” he says. “You guys probably get hundreds of requests a day for projects.” Wheeler eventually became director of the Navajo Nation Museum in Window Rock, Arizona, and he continued to reach out to Lucasfilm -- never the same email address twice -- until one day it finally happened.

For years, Wheeler would email and call Lucasfilm. Not every day, but sporadically, just to see if he could find someone interested in making a Navajo-language dub of A New Hope happen. “I wasn’t kidding myself. This was like, Lucasfilm,” he says. “You guys probably get hundreds of requests a day for projects.” Wheeler eventually became director of the Navajo Nation Museum in Window Rock, Arizona, and he continued to reach out to Lucasfilm -- never the same email address twice -- until one day it finally happened.

On our Zoom call, Wheeler takes a frame down from the wall. A printout of an email sits beneath its glass. “It was from Michael Kohn at Lucasfilm. He said, ‘Your email below was sent to me today. I’m reaching out to discuss your proposal.’ That was January 30, 2012," Wheeler says. "I don’t know if I yelled, but I definitely called my wife, first thing. That’s how the process started.”

After a few discussions, Lucasfilm gave a handshake blessing and Wheeler got to work spearheading the project. It was a lot, but he wasn’t on his own. “Michael Kohn really put me in great hands with Shana Priesz,” Wheeler says. “Shana Priesz has been in the dubbing business for a long time, and she really knows her stuff. She came out to the Navajo Nation, and we visited the only studio that was around. It was a music recording studio. She saw that they had the capabilities to record.” Priesz sent her engineer and also brought a director, Ellyn Epcar, on board. “She put us in the right technical hands,” Wheeler says. Wheeler handled auditions, something he’d never done, and cast the entire track. By the end of 2012, the recording was complete.

“We couldn’t believe what we were seeing”

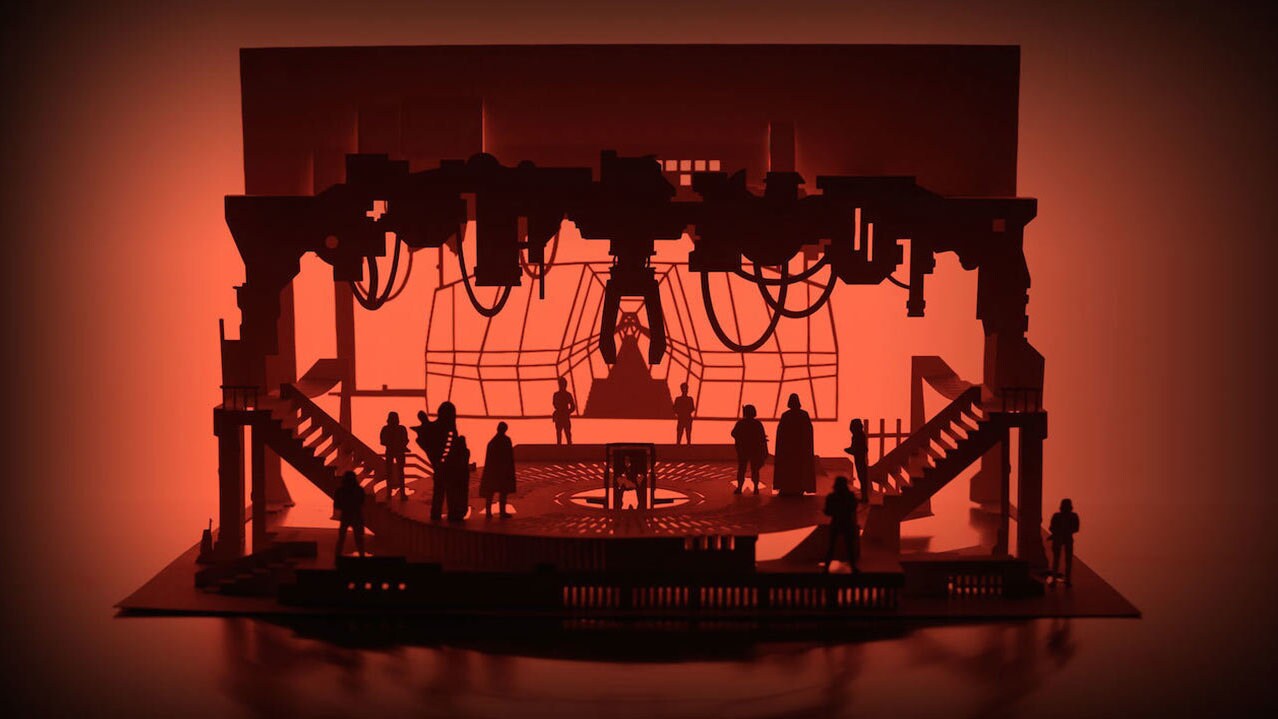

Wheeler recalls the first time he watched A New Hope with the Navajo dub. “We watched a rough edit of it at the studio in Gallup, and that was slightly emotional,” he says. “You were more elated. The crew, the engineers, the director, myself, a couple of the translators. It was just a really tiny group. We watched it and we couldn’t believe what we were seeing. It was disbelief.” It wasn’t until he saw the final version of the film with the Navajo audio track that he’d realize the full impact of what he and his collaborators had accomplished.

Disney, who had acquired Lucasfilm toward the end of the project, offered up an executive screening room at its Burbank headquarters for Wheeler and friends to watch the completed work. “The Navajo Nation president and vice president came, myself, my wife, and some other executive Navajo staff. And that’s the first time I teared up. My wife, we just looked at each other. We couldn’t believe it. Even the [opening] crawl was done in Navajo.”

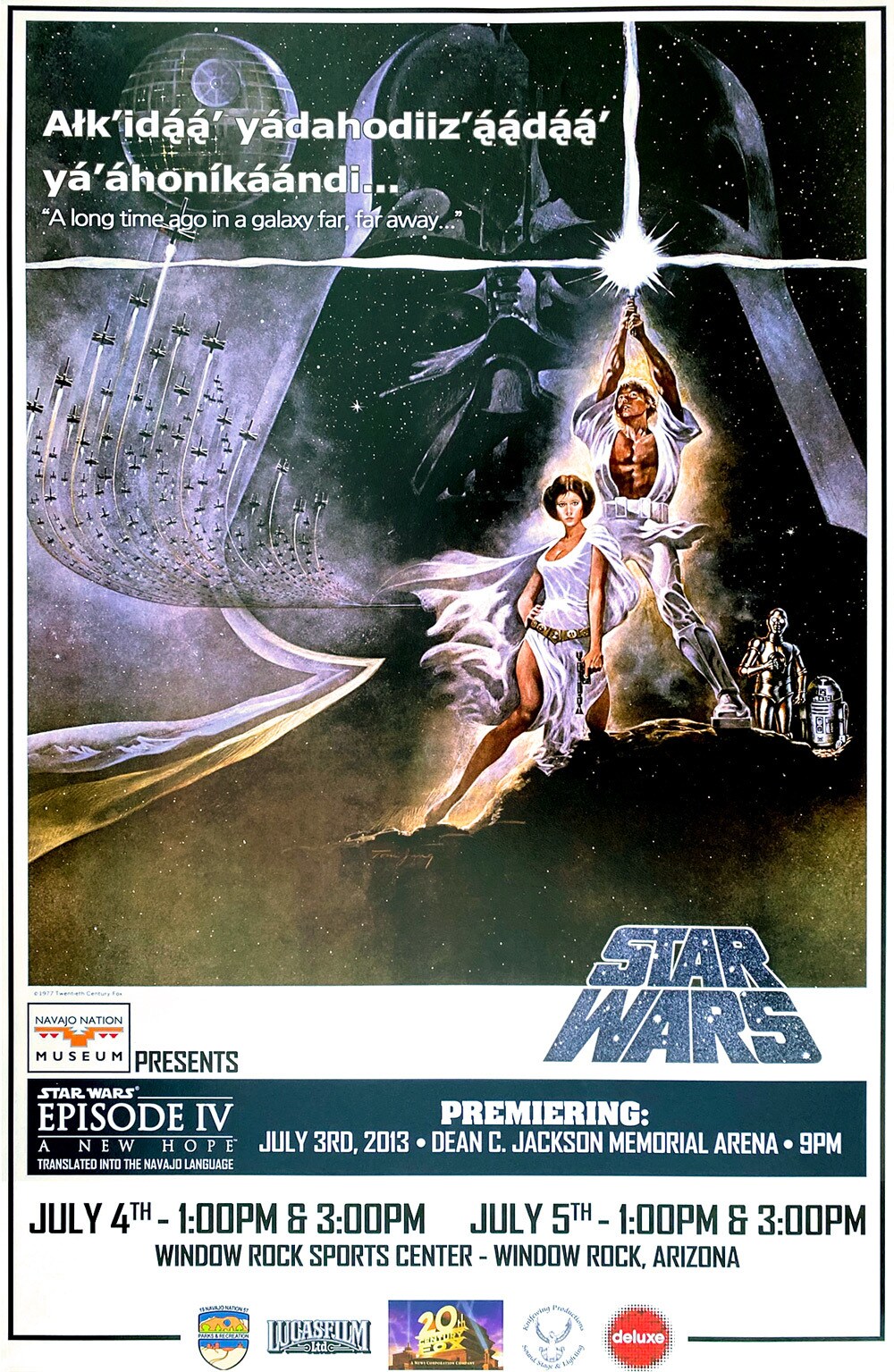

Wheeler then took the dub back home for various openings and screenings, noting that strangers would approach him after the film to tell him how much it meant to them. The Navajo dub of A New Hope would become the springboard for more translations, including, most recently, Finding Nemo.

Today, the Navajo audio track of A New Hope is even available on Disney+, taking the language and Wheeler’s labor of love to a wider audience than he could have ever imagined. “It’s worldwide. A Navajo person who lives in New York City, if they want that connection with their culture, they have the ability to turn on their smart phone and watch Navajo Star Wars on it,” he says. “That, on a basic level, is very powerful. There are a lot of points about what Navajo Star Wars is and what it has done. Even for a non-Native person to be flipping through and say, ‘What’s this? Navajo Star Wars?’ That’s bringing awareness. ‘I didn’t even know Navajos had the ability to do this.’ To me, that’s another powerful point. It shattered the world’s perception of Navajo people and Native people.”

Even with this great impact, Wheeler points to a singular achievement that made all those emails and phone calls worth it.

“This project, it welcomed Native people to be part of the Star Wars universe. That’s real important, because Native people, in my opinion, we’re always on the outside looking in,” he says. “Star Wars really helped bring us inside. Now, our Navajo young people just have this attitude of like, ‘Oh wow, cool.’ They’re excited about it. ‘Yeah! That’s what we do now. We can do it.’ Star Wars has the ability to do something like that.”