Most Impressive Fans is a feature highlighting the amazing creativity of Star Wars devotees, from cosplay to props. If there’s a fearless and inventive fan out there, we’ll highlight them here.

Han Solo's beloved ship has been called a hunk of junk. A bucket of bolts. Garbage.

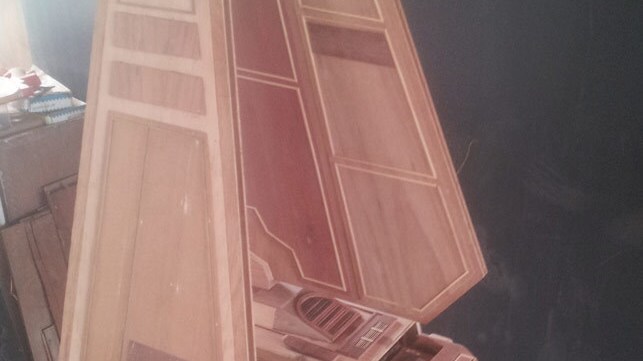

Add to the list: “a huge, bloody monstrosity.” That's Martin Creaney's description of his own massive Millennium Falcon sculpture, a 6-foot-long, 5-foot-wide wooden behemoth on display inside his home in Australia.

The former woodworker-by-trade earned the right to christen his ship after he built the hulking freighter over 15 months. He made all the special modifications himself, “though I doubt that I'll ever truly consider it finished,” he says.

With a strip of glowing backlights, a rotating laser cannon and sensor dish, and the pristine finish that gives the solid timber piece a wholly unique look, the sculpture is also a work of art. So much so, this summer it occupied the corner of a gallery near Martin's home during a special showcase.

Don't worry, she'll hold together

Martin, 44, had worked as a cabinetmaker during his early career, but after moving on to a new job he decided to take his knowledge and apply it to something besides basic furniture.

“I started building myself a workshop just so I could do different things,” he says. “One thing led to another and I found myself building the Falcon, not realizing at first just how big it was going to turn out.”

His plans were for the front third of the ship, which he intended to mount in his home, near the city of Ballarat outside Melbourne, as if it were in the middle of crash landing through his ceiling. “And as I was doing it I thought, 'You know what? I've come this far, why not do the whole thing?'”

By then, it was too late to scale down. “Once I decided to make the whole thing, I couldn't really stop,” he says. “It became this thing that I had to keep going with.”

Early designs called for a composite hardboard panel shell, but the effect would have been so plain it would have required a paint job to match the film version.

Instead, Martin opted for a more unique exterior, using bits of solid timber in a variety of shades, an arsenal of sanding tools, and plenty of wood glue to try to match the used-future feel of the original prop model.

Saving up

Because so much of the Falcon's rough exterior is due to a menagerie of smaller parts artistically cobbled together, Martin barely had to sink any money into supplies for the project.

“Admittedly, I never really looked at how much money I was putting into it,” he says. “I've been getting into doing more decorative woodworking, so over the years I've kind of collected bits of timber from here and there and everywhere.” Larger projects with more intricate designs often leave a pile of oddly shaped discarded pieces, but Martin can always find the beauty in even a chunk of raw timber no bigger than his thumb. “I might be able to use it for something else so I'll just put that aside.”

In fact, he collected so many smaller cuts of wood over time that at one point he had to build a set of cabinets just to hold all the pieces, like any voracious crafter with a massive stockpile of raw materials for projects yet to be dreamed up.

“I've almost stopped throwing out off-cuts,” he says. “So I've made a set of drawers so that I can fill it with all these little bits of timber that I may end up using for a future project. It was simply out of necessity because otherwise...at one stage I just had cardboard boxes full of these little things just shoved into corners and on bench tops.”

With the help of a cache of online photos showing every minute detail of Han's beloved Corellian light freighter, Martin scoured his collection for the best materials then set to work smoothing raw edges with sand paper, cutting with his scroll saw, and turning some of the most detailed parts on a wood lathe.

“The lathe became almost my go-to tool for doing a lot of those little things,” he says.

The project still brought plenty of challenges.

“Just the sheer number of little detail-y parts on it was a big challenge,” he says. “After a little while I realized, 'Oh good god. This is going to take forever to do.' Just the amount of detail that's actually on this thing is ridiculous.”

Ultimately, he made the executive decision not to spend an additional 15 months accurately detailing the underside of the hull. But on the top side, Martin set his sights to create an immaculate replica, as close as he could get to the real thing. “With almost any of the builds that I've done...there's not much point in doing it unless you actually commit to doing a level of detail.”

That meant making a laser cannon and satellite dish that could rotate, even though wood is an inherently fickle medium given to subtly changing shape when the weather changes.

“I enjoy that sort of thing. That little bit of problem solving that comes along with trying to make things that can move,” he says. The nature of timber, it will expand and contract. So when you're trying to make parts that can actually move, if it's too loose they're just going to flop around and if it's too tight then you're going to potentially break things when you try to move it.”

A tiny cog-and-wheel assembly with a metal arm was the fix for the dish, but only after he'd had to remake the entire thing twice because the first attempt was just too small.

“It was the same similar sort of thing with the laser cannon. When I made that it was, 'yeah OK I could just have it as a static fixed thing but making it so that it can actually move, pivot, move around like it would potentially in a real-world kind of situation was a bit of fun.”

Do. Or do not.

Still, he got frustrated while diligently working for about 18 hours per week throughout five seasons.

“There was certainly times when I was making that I just had to walk away,” he says.