On May 21, 1980, Star Wars: The Empire Strikes Back made its theatrical debut. To celebrate the classic film’s landmark 40th anniversary, StarWars.com presents “Empire at 40," a special series of interviews, editorial features, and listicles.

The farm boy from Tatooine had grown up. In February of 1979, Mark Hamill was ready to return to the role of Luke Skywalker, arriving in the unforgiving snowscape of Finse, Norway, for his first day of shooting on a frigid location shoot that would transport viewers to the planet Hoth. For four months, he had trained in karate, fencing, kendo, and bodybuilding, preparing his body for the strenuous stunts the new script called for. Hamill had always been game to do his own stunt work, like swinging over the chasm inside the Death Star, but the sequel, The Empire Strikes Back, would prove to be the most physically-demanding and isolating experience of his long career in the role.

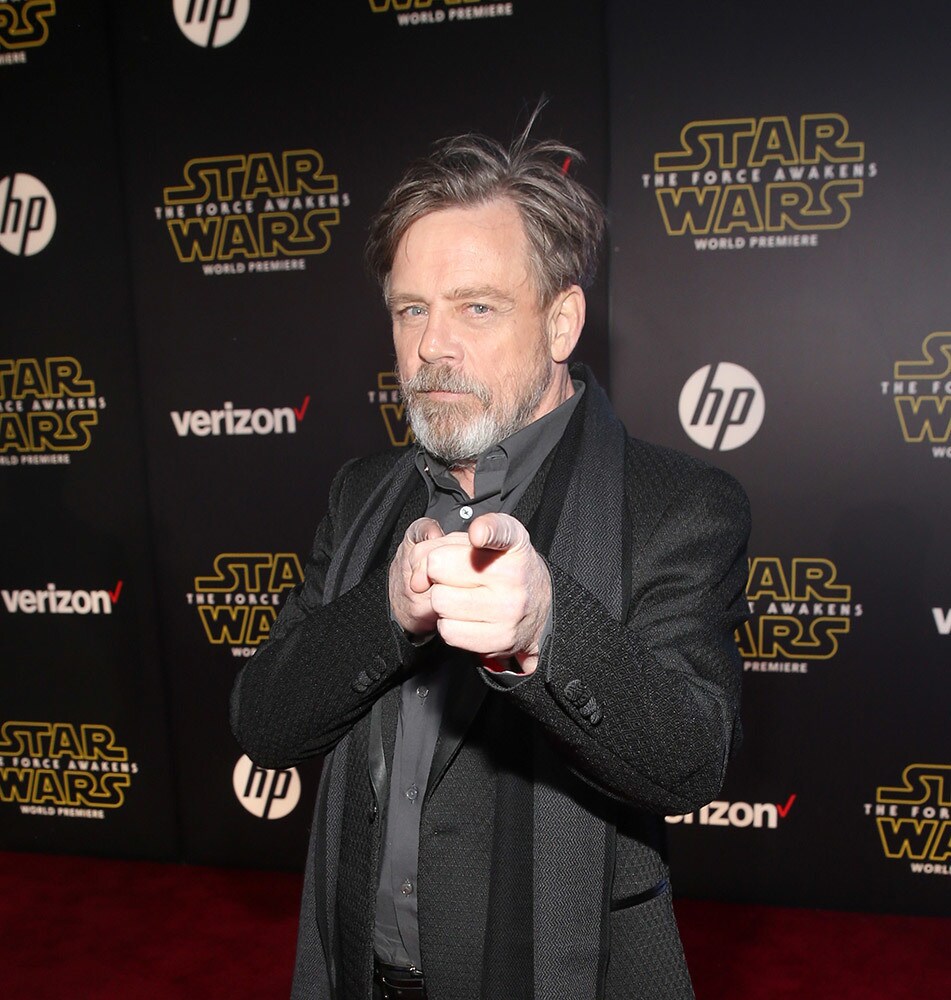

Speaking by phone from his home outside Los Angeles, Hamill exudes the affable charm and graciousness of a man who’s been embraced by Star Wars fans for decades. “I’ve been talking about this so much, you know, my kids mouth the answers I give because it’s been 40 years,” Hamill says at the outset. But he’s game to take another spin through his memories of filming The Empire Strikes Back as we celebrate the film’s 40th anniversary later this month.

Hamill knew during shooting of what would become A New Hope that the movie was the start of a trilogy, and that was “one of the reasons I tried to emphasize [Luke’s] immaturity,” he says. “You know, I get mocked a lot for, ‘But I was going to Tosche Station to pick up some power converters,’” he says, his voice going higher in an exaggerated whine. “But I did that intentionally to be able to grow and make him as much of a clueless teenager as possible, because by the end of the film he has found his purpose in life and he’s so profoundly changed,” Hamill says.

Behind the scenes, everything was different, as well. “It was a really pivotal time in my life because [my wife] Marilou and I were expecting our first child,” Hamill says. Nathan Elias would be born once the Hamills were back in England shooting in June of 1979. Among the cast and crew, “there was a marked difference in the attitudes,” he recalls, “because on the first one nobody knew about us or cared. I mean, I remember passing the script around to my friends saying, ‘Hey, you gotta read this. It’s the craziest thing I’ve ever been involved in.’ There was no social media. There was no security. There wasn’t any focus on this unknown science fantasy film, but everything changed after that. So on Empire, suddenly…we had to be really careful.”

30 feet from the hotel

From the start, arriving in Finse, Hamill and the crew were under tremendous pressure, battling the brutal elements of an extremely harsh Norwegian winter that included blizzards that shut down the train lines and essentially stranded the crew at their hotel. “They had scouted a location that was going to take us 90 minutes to get to, where there was a glacier that had blue ice that photographed blue on camera,” he says. “I was very excited to see it and then, as happens in filmmaking, it was one of the worst snowstorms in I don’t know how many years. We wound up filming right outside the lodge. I mean, if you turned the camera around you saw people on their balconies having their hot chocolate as Harrison [Ford] and I were acting next to a dead tauntaun.” About 30 feet from the door of the hotel, Hamill endured take after take, lying in the snow as the injured young rebel glimpsing the specter of his former master. “It’s funny because if you see the photos where the crew is included, they’re all in goggles and masks and you know they’re just completely bundled up. I would stay bundled up right until we had to shoot, then the protective gear would come off and obviously the wardrobe is designed to look good but not actually be practical in terms of keeping you warm in those conditions. And I remember I was supposed to be sort of groggy and semi-conscious when Obi-Wan comes to me in the vision. And they’d say, ‘Get a little more snow on his face!’ and Graham Freeborn [the chief makeup artist] would scoop up snow and pack it so it would be in my eyelashes and eyebrows,” Hamill says. “You’d go as long as you could and then you’d try to get in a tent and get warm until they needed you again. Certainly a challenging environment. I mean, North Africa could be warm, but that you can handle better than bitter cold,” he adds, comparing the blistering sun of the Tunisia location shoot for Tatooine to frigid Hoth.

“Harrison wasn’t even supposed to come to Finse,” Hamill notes, a change in the shooting schedule that reunited the core trio as the production began to experience its first hiccups and delays. “He was going to do all his scenes back at Elstree in England, but because of the weather altering our schedule, he came out. And Carrie [Fisher] even visited even though she didn’t film. She just wanted to hang out and it was fun to have her there.”

While the three friends spent some time together between takes, Hamill says the demands of the story -- pulling the core trio in opposite directions -- meant most of the shoot was quite isolating for the actor. “It was a very solitary experience in many ways because Luke was separated from Han and Leia. And I’d see [Carrie and Harrison] around the studio and I’d see them in dressing rooms now and then, but it made me sort of nostalgic for the days when we were all together running around the Death Star. When we were all three together it was really a lot of fun. And in this one, I mean…for months I was the only human being on the call sheet. ‘Actor: Mark Hamill. Role: Luke Skywalker.’ And then under props it was, ya know: ‘snakes, R2-D2 unit, Yoda,’ and so forth.”

“Every possible stunt”

Over the course of the shoot, Hamill performed so much of his own stunt work he was later made a member of the British Stunt Union, although on occasion the insurance company would step in to deter him from, say, tumbling through the fake glass window on Bespin to a sea of mattresses below.

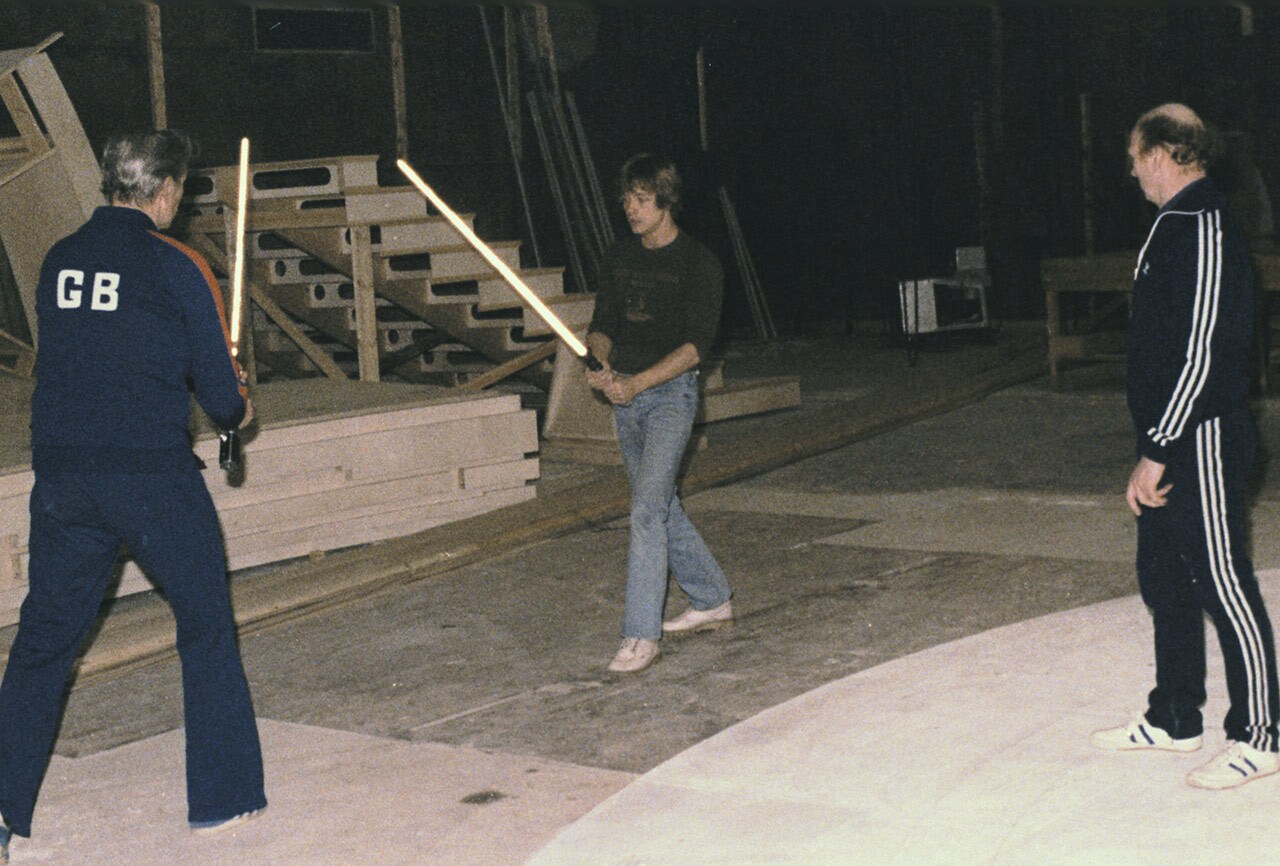

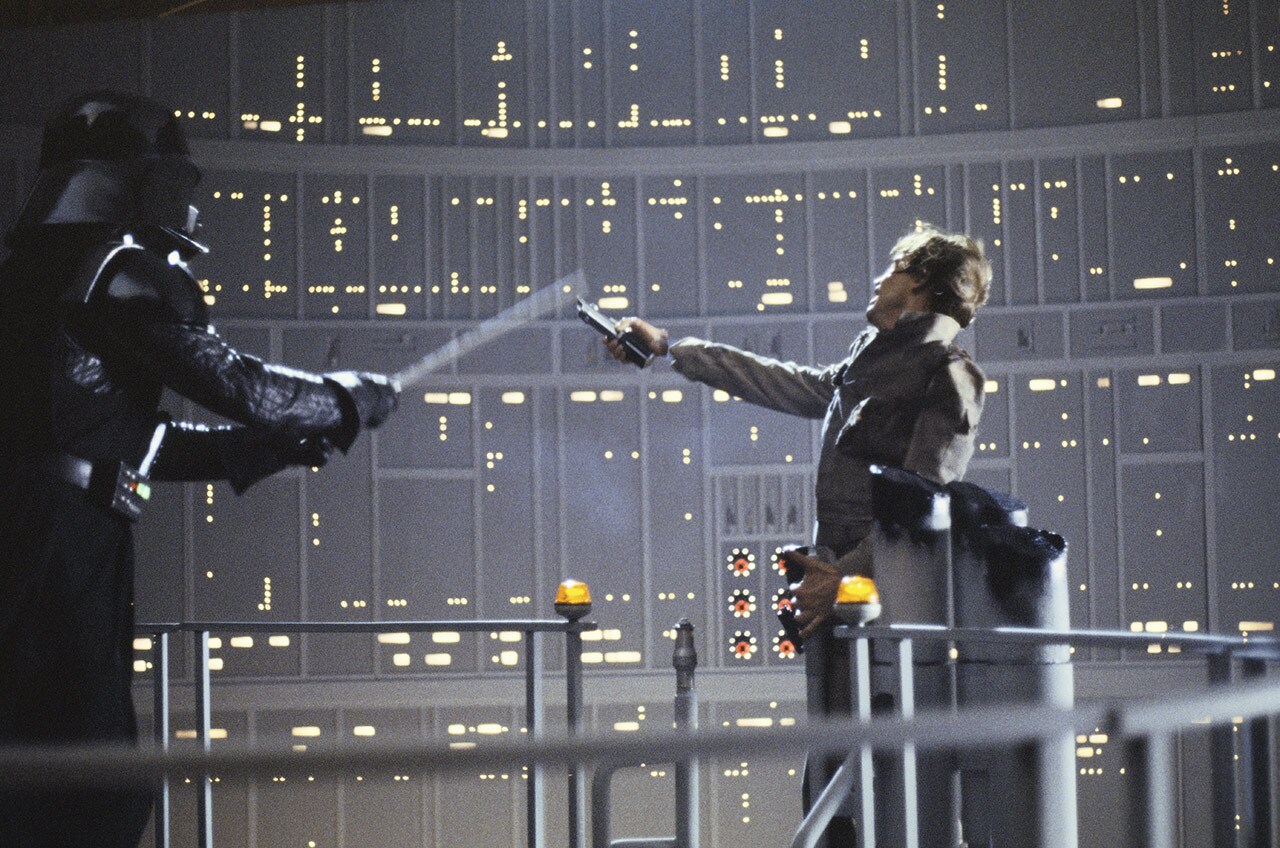

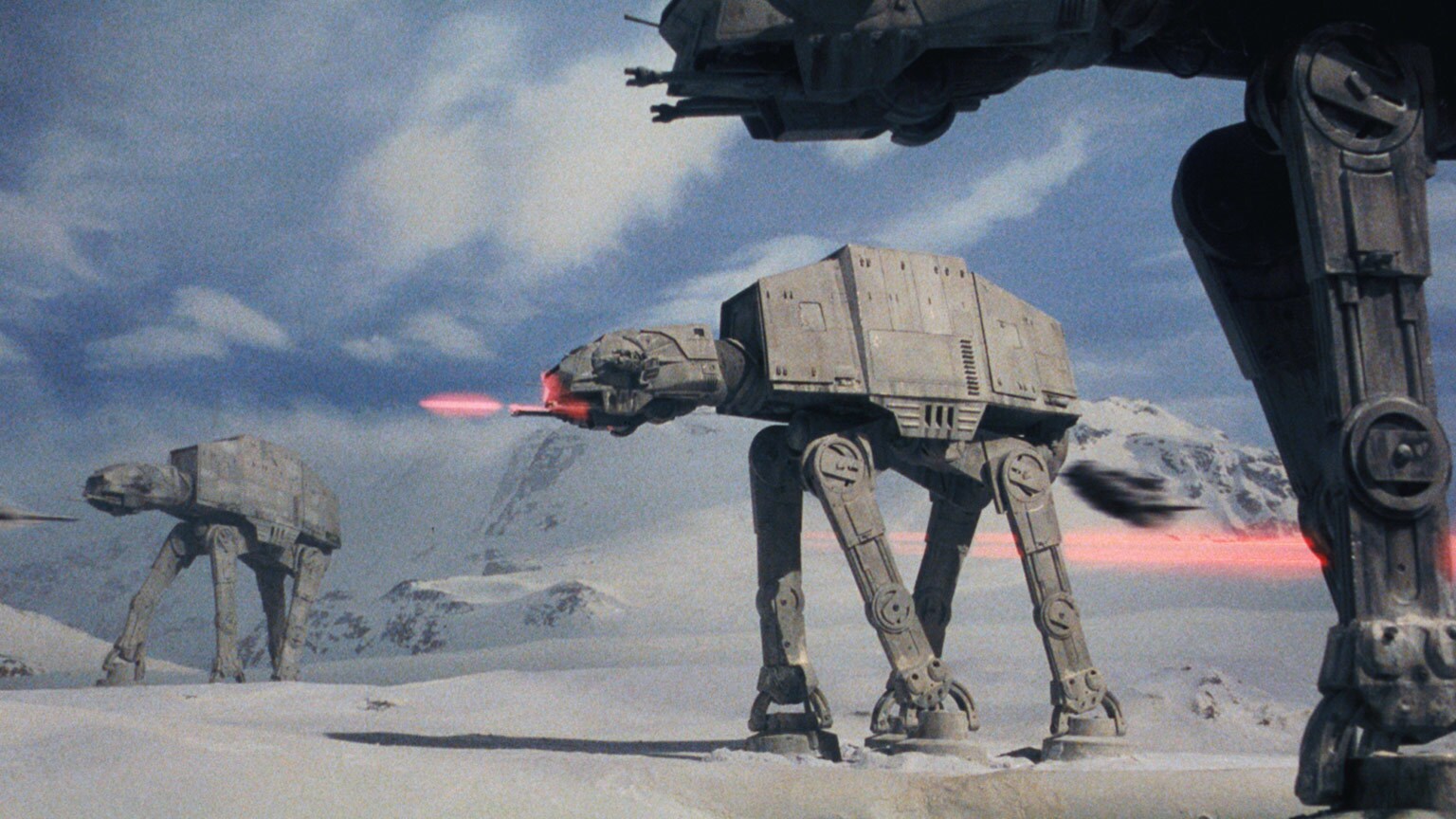

“And I’ll tell you something, in those days -- it’s changed as I’ve gotten older, -- but in those days I wanted to do every possible stunt I could,” Hamill says. “[Empire] was the most physically grueling of them all because of the lightsaber duels and all that.” The film was the first time Hamill would take up the weapon of the Jedi for a proper battle with Darth Vader, and the duel itself -- although delayed on the shooting schedule after he injured his thumb diving away from an imagined AT-AT on a salt-covered soundstage the day his son was born -- required far more acrobatics and choreographed footwork than the straightforward sparring between Vader and Kenobi in A New Hope.

“I worked with Peter Diamond who was the stunt coordinator, and Bob Anderson who doubled Vader, who was an Olympic Fencing champion, so there was intensive training. We had worked out a sequence we were all particularly proud of. And I’m talking weeks and weeks of this…and we said, ‘Let’s bring George [Lucas] in.’ We brought George in to look at what we had done and he said, ‘Um well,’” -- Hamill says, his voice shifting into his best Lucas impression for a beat. “’You can’t take your hands off a lightsaber. You can’t hold it in one hand.’ And we said, ‘What?’ We had choreographed stuff where, you know, we did spins around and we did various things….He didn’t want us to ever take both hands off the hilt. So we had to go back and re-choreograph that whole thing. It was frustrating, but I was very lucky to have Peter who was so skilled as a stunt coordinator, and Bob. He was someone who, he could counter if I made a mistake, he could counter it and incorporate it into the routine and we could keep going. It takes an expert to make a novice look good, and that was certainly the case with him.”

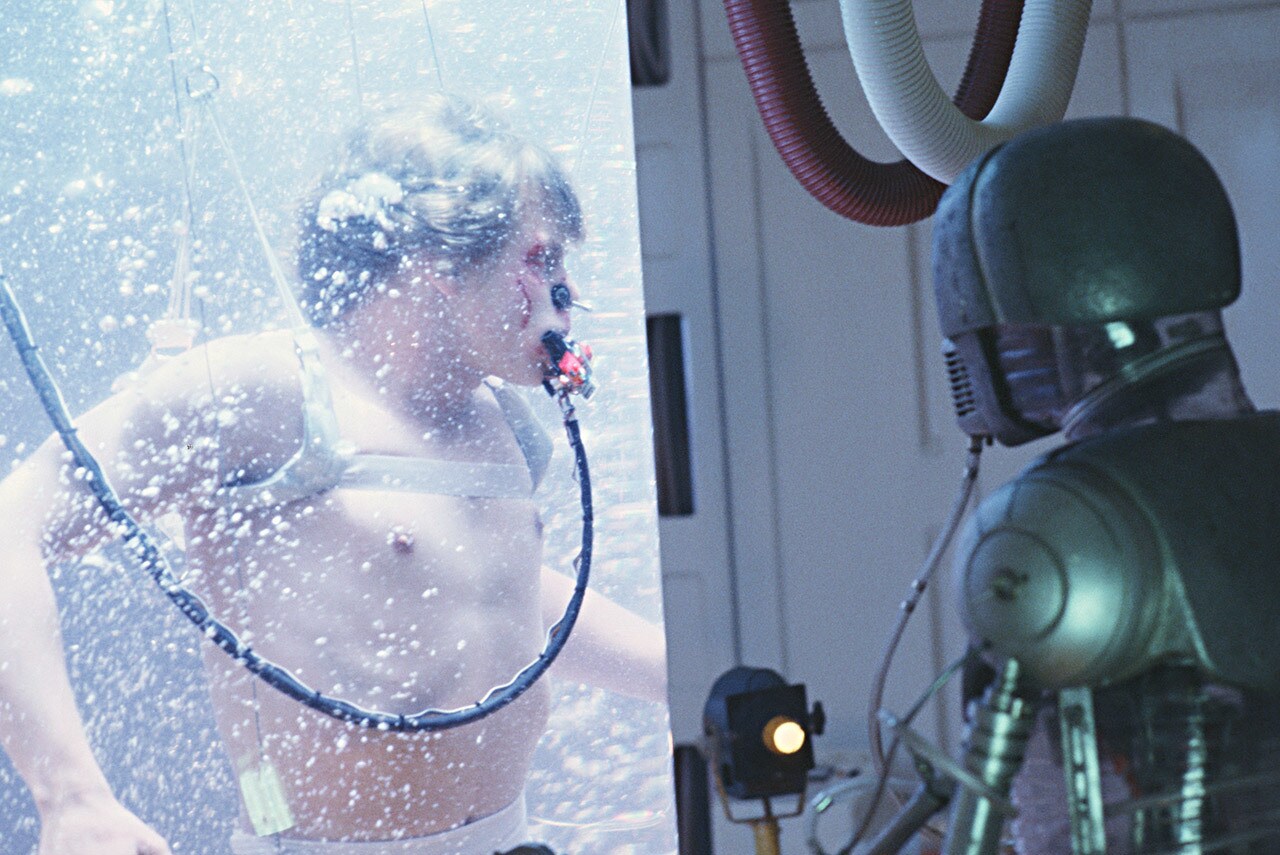

For the scenes inside the bacta tank, Hamill got a crash course in scuba diving. “They took me to a private school that had a big enough swimming pool because I had never been scuba diving before. And I said to them, ‘Well I don’t think it’s any big deal. I’ll just breathe through the tank. What’s the big whoop about that?’ And they said, ‘Well, you’d better try it.’ So, I went to an all-girls school and they had the swimming pool closed as I had my lessons, but I remember, at one point, looking up and on the second floor balcony there were, I don’t know, 50 girls all up there giggling and pointing and laughing,” he says. “So that was interesting.”

The stunt inside Elstree was a far cry from the chilling experience on location. Hamill found it quite relaxing, he says. “It was wonderful because the water was warm enough to be comforting and it was very much like being in an isolation tank. [Luke is] supposed to be unconscious so you’re just floating there….It was surreal because you could look out and see the outlines of Harrison and Carrie and [the director] Irvin Kershner and the crew. It was a unique experience to me. I don’t think I’ve ever done anything like that since.”

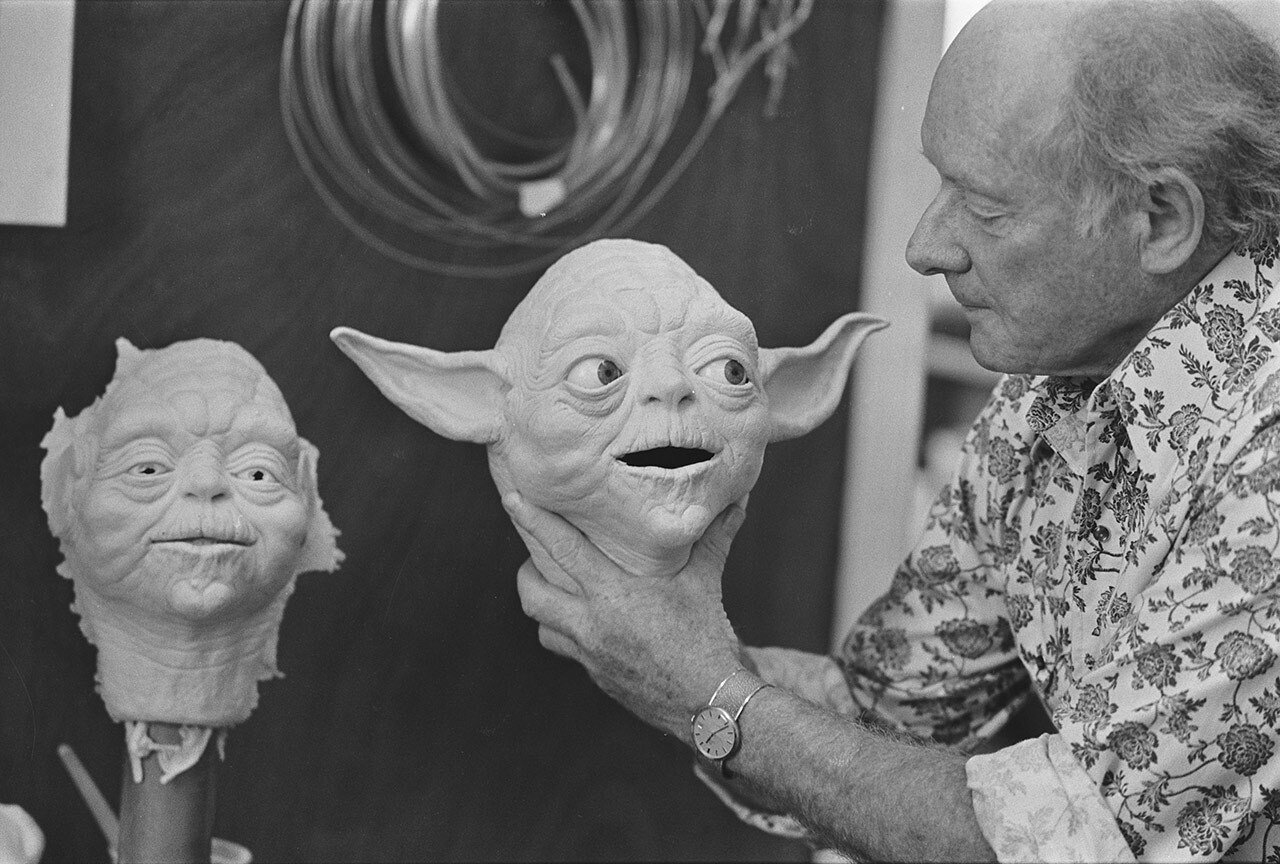

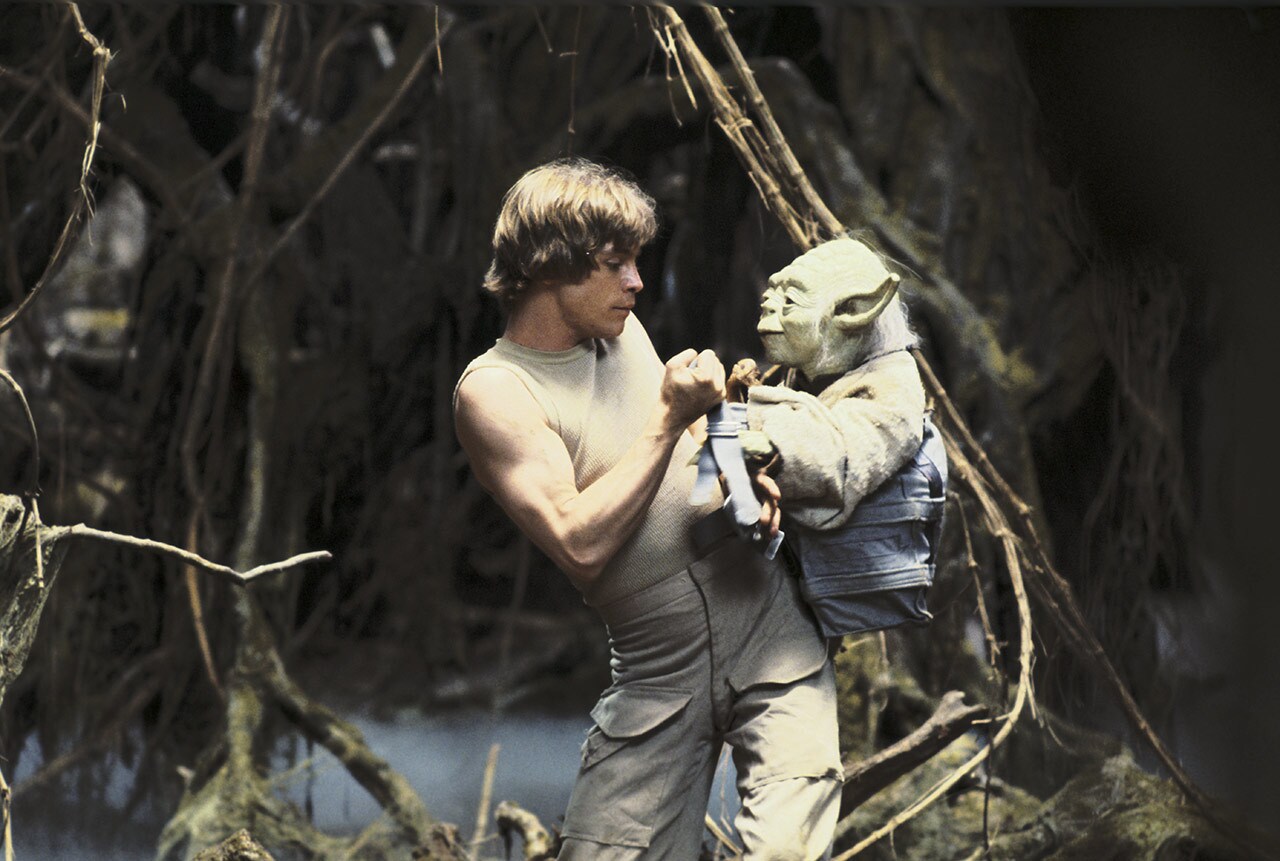

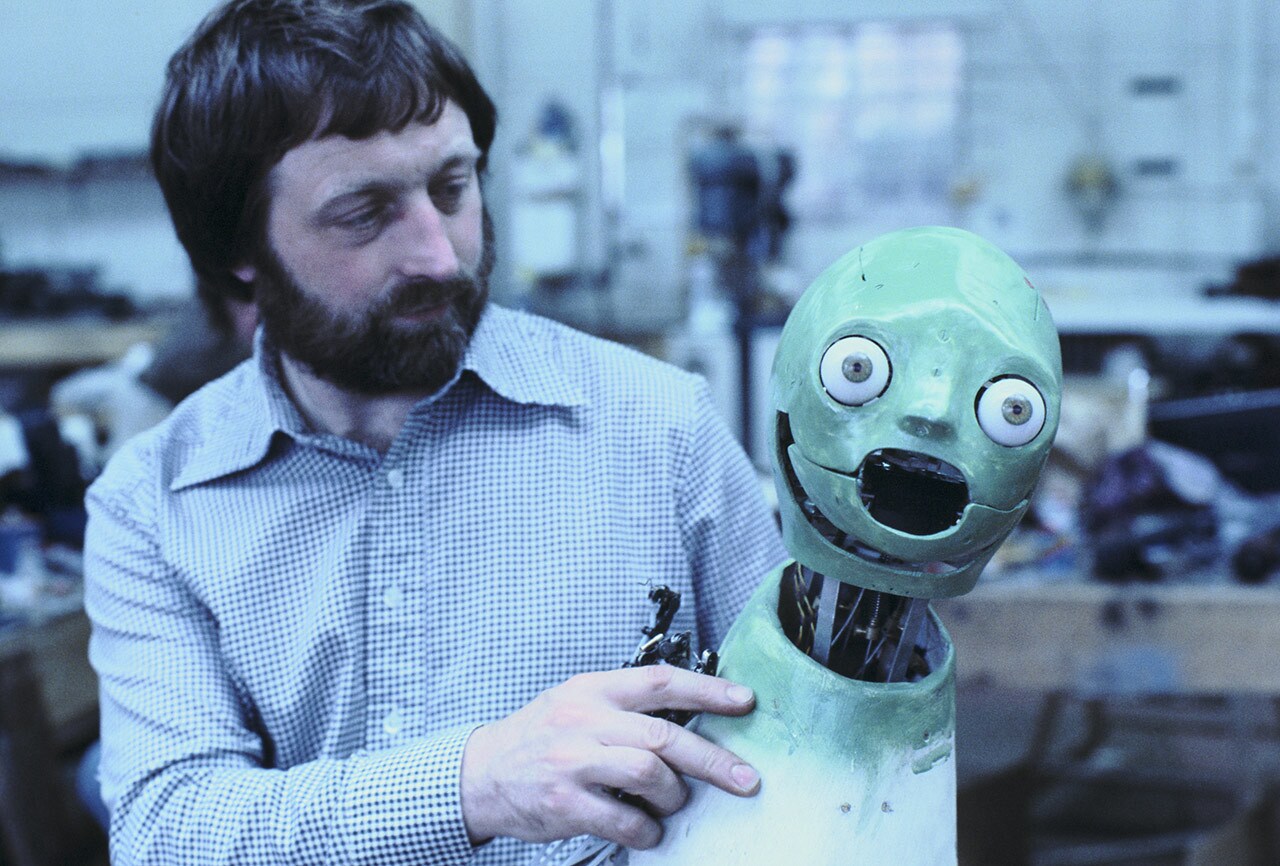

Among the final scenes to be shot were Luke’s training on Dagobah. The practical effects that brought Yoda to life were brand new at the time, a feat of skilled puppetry, but also gears, and motors that would often require tinkering on set, Hamill says. “We had rehearsals with Frank [Oz], and I had no trouble believing [Yoda] was real because he was real to me. You wanted to believe. And Frank and his crew, Wendy [Froud] and Kathy [Mullen] were so talented. But it was lonely, because they buried them in their trench when they were shooting. I didn’t see them really until in between takes when they would come out.”

To complicate matters, the earpiece that helped Hamill hear Oz’s vocals while the puppeteer was down below would accidentally tune in to the local radio station. “The earpiece worked fairly well. The trouble was, depending on what position you were in you could pick up radio waves and all of the sudden you’d be hearing Top 40,” Hamill says. “The two songs I remember was ‘Fool to Cry’ by the Rolling Stones and ‘More, More, More,’ that disco song.” Hamill briefly breaks out into song. “’More, more, more! How do you like it? How do you like it?’ The first time it happened I sort of giggled and broke and Kershner said, ‘Look, it’s really important that you don’t do that,’ because Yoda, I mean, we keep calling him a puppet but at the time he was a really sort of elaborate electronic prop that had never been tried before. He was in constant need of upkeep. He would break down. He would blink, his ears would move, and then, of course, Frank brought him to life. But if the electronics failed, he would have to go back up to Stuart Freeborn’s lab and be tinkered with.

“You’d hear ‘Many years have I….Ooh, daddy you’re a fool to cry,’” Hamill says, his voice blending from an impression of Oz as Yoda to Mick Jagger singing. “[Kershner] said if that happens again, which it did, just keep a straight face so we can get usable footage.” Hamill learned to watch Yoda’s mouth, unspooling his next line when the puppet paused. “It could be extensive. Sometimes you’d hear the radio for 30 seconds. And you know, from then on it was a real challenge, but we got it done.”

And when the hero prop was in the shop, Hamill could continue filming his own lines with the help of a pair of simplified decoys. “There was a stunt dummy Yoda that they would use. Any time you see me in a single [shot] without him in it at all, I’m usually looking at a stick with a piece of tape on it for an eye line. And a lot of times they used the dummy one if it was over Yoda’s shoulder onto me because it was inarticulate, but the back of it looked the same as the proper one.”

Big reveal

Of course, even when shooting wrapped and Hamill was able to rest up, his work on Empire included shouldering the secret of Luke Skywalker’s parentage for more than a year. Not even David Prowse, the man inside Vader’s suit for the scene, knew the truth until the film’s premiere.

“Here’s the part where my kids can mouth the words because I’ve told the story,” Hamill says. One day before shooting the pivotal scene, Kershner pulled the young actor aside for a routine script change. “In the script that everyone got, the line was, ‘You don’t know the truth. Obi-Wan killed your father,’” Hamill says. “I thought, ‘That’s a major twist!’ If Alec Guinness is the ultimate bad guy, I didn’t see that coming.”

But just before filming, Kershner revealed an alternate twist, left off the page to preserve the secrecy. In the moment on screen, Darth Vader would tell Luke, “No, I am your father.” “Kershner said, ‘I’m going to tell you something. I know it. George knows it. And when I tell you, you’ll know it. But that means, that’s only three people. So if it leaks, we’ll know it’s you.’ So the burden of keeping that a secret for over a year, maybe a year and a half, it was enormous. It was immense. Like I say, there was no social media and I wouldn’t leak it anyway, but I talk in my sleep. I was terrified having that knowledge.” At the first cast screening, Ford was miffed by being left out. “Harrison turned to me when that happens and said ‘You didn’t effing tell me that.’” Hamill says, growling his best Ford impression. “I said, ‘I was afraid! I was too afraid!’” And during the shoot, no one on set was the wiser. “Other than that the scene played exactly as it did. It surprised everyone!”

That willingness to alter course, creating a moody film noir-like space fantasy in the wake of the jubilant rebel victory at the end of A New Hope, is one of the reasons Hamill believes Empire was so successful and continues to rank high among fan favorites in the Skywalker saga. “One of the things about the movie that I liked is a lot of the time sequels just try to repeat the experience of the first film that it’s based on. In the case of Star Wars, it would be one of those almost amusement park rides that you just strap in and go along for the ride and have the euphoric triumphant ending, and everyone lives happily ever after and it’s thrilling and all that. But this one was so much more cerebral. There was a spirituality about the Force in the first one, but this one, with the addition of a character like Yoda, it just knocked me out reading it. It was so much deeper. It was so much more challenging to the audience and, of course, so dark and so shocking that it ended with us defeated, you know? And Harrison turned into a coffee table. It was tragic all-around. It was just terrible. But it was really exciting to me. I thought, This is sort of the make or break.’ If this one doesn’t resonate with the public, the future of the franchise -- and at that time I was only thinking the trilogy -- it’s pivotal that this movie connects….I thought if this one tanks or the audience rejects it, we’re all in big trouble.”

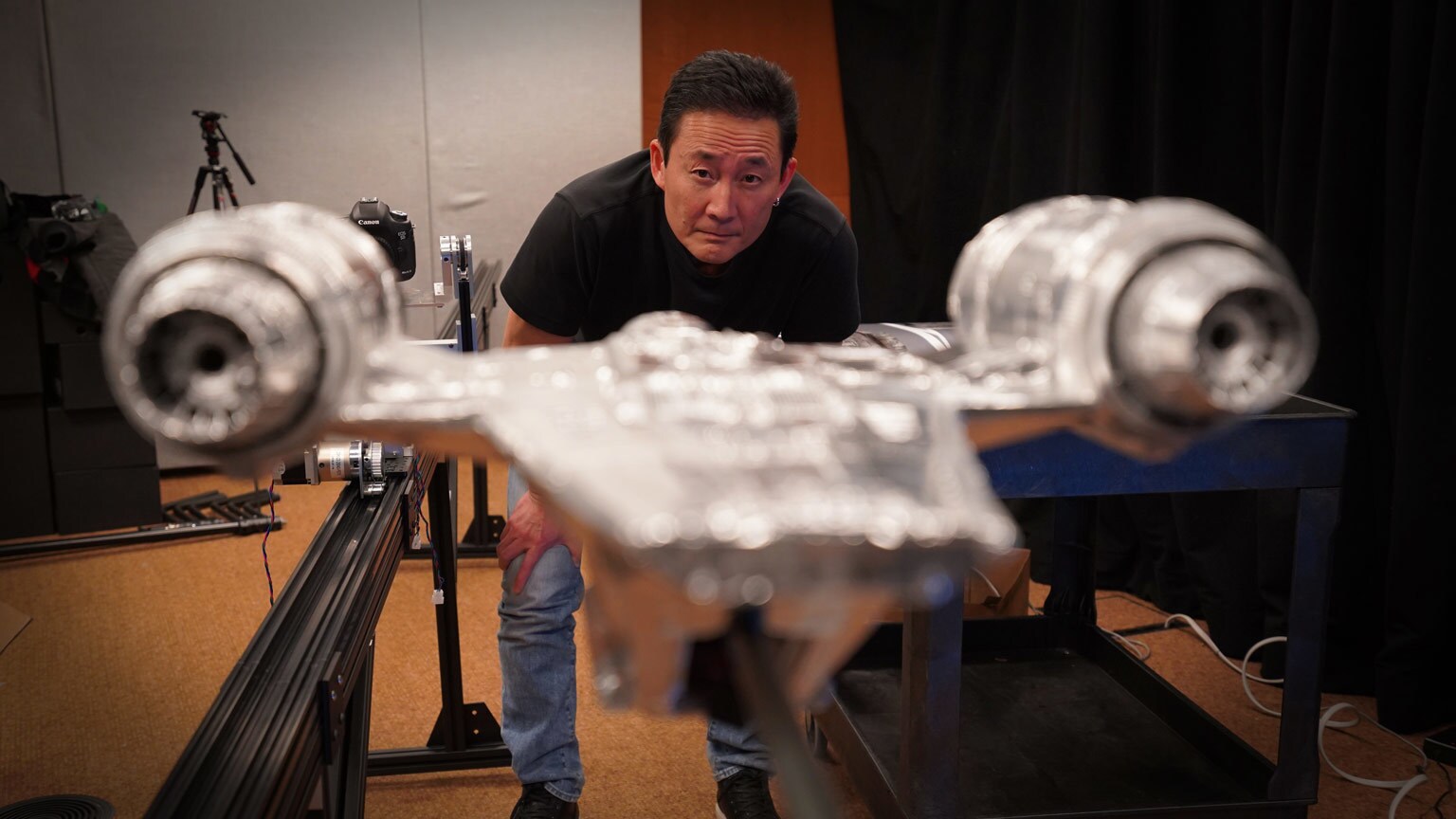

But some 40 years later, fans continue to embrace the dark sequel, ending with the Rebel Alliance on its heels and Luke Skywalker at his lowest point, physically exhausted, badly injured, and emotionally defeated. The story, the characters, and the power of the Force still resonates today as much as the special effects and the unforgettable score.

“I think it’s primal,” Hamill says of the need for stories like Star Wars. “I think it’s the way Grimm’s Fairy Tales last throughout the years. I always thought, when I read [Star Wars], I thought this is much more a fairytale than it is traditional science fiction. Because there’s a princess and a farm boy and a pirate and a wizard….We’re lucky that George was able to imbue it with such humor. I remember reading it and thinking, ‘It’s so funny!’ You know, there’s just great moments of the robots arguing over whose fault it is, the princess not wanting to go in the ship she’s rescued in. It’s so relatable! It’s so human. Here she is, royalty, and it’s like your dad picking you up in the beat-up car that embarrassed you in front of your friends. It never lost its touch with the humanity. So yeah, there was the fantasy aspect and the special effects and, of course, John Williams’ score. You can never underestimate how powerfully it aided our cause. But just in terms of sheer storytelling…you know, it connects with people. It’s overall a very optimistic story. It’s really uplifting and people need that reaffirmation that people are basically good and that they will help each other. It’s about doing the right thing selflessly for the greater good and it’s reassuring, I think.”