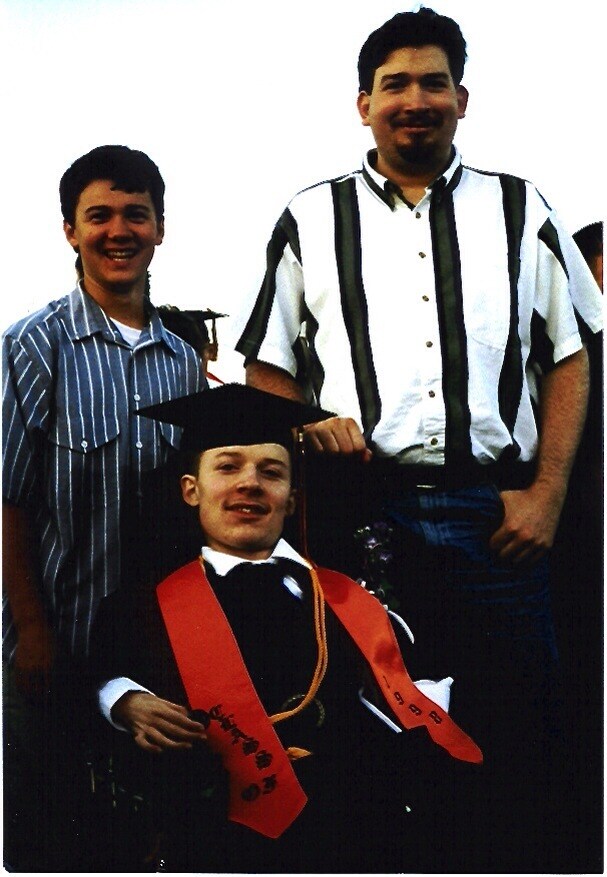

In May 1997 just after the re-releases, I attended my first Star Wars convention, reuniting with my fellow actors for the first time in 18 years. The event was in Hackensack, New Jersey, just across the Hudson from New York City and the Twin Towers. In the nineties, I donated all my proceeds for children’s charities, and at the Hackensack show, I raised money for the Make-A-Wish Foundation, the non-profit that fulfills the wishes of children under 18 with life-threatening illnesses. At my table, the Make-A-Wish representative who would sit with me to handle the cash transactions through the weekend told me the convention had sponsored a dedicated young fan from Scappoose, Oregon, a bedroom community just northwest of Portland. He was there with his best friend, his brother, and his parents.

An 18-year-old Ben Fitzgerald arrived in front of my table driving his hot rod landspeeder: a high-tech, Swedish wheelchair. His third upgrade.

His brother Luke served as his droid. Ben had Duchenne muscular dystrophy, a disease that progressively deteriorates muscle tissue and is generally fatal by a person’s early twenties.

Ben was a young man who ran his own show, dexterously maneuvering his craft with the controls on his armrest, his head tilted slightly to one side against a restraint as he scanned the terrain around him. We chatted about Star Wars and his dog named Princess Leia. With long lines forming behind him, we couldn’t go into much detail, so I invited him to sit with me behind the table as I signed after he finished making his rounds. He went off. Sometime later, he came back, wheeled around to position himself to my left and spent the better part of an hour conversing and listening in on my chats with fans. Questions I couldn’t answer, I referred to him. Ben was the expert.

Star Wars is a vehicle for all our individual personal beliefs -- whatever they may be. And Ben was a young man on a path, a mission, very certain of his aims. Until the age of seven, he had been able to walk. From those early days, his companion had always been Ryan Proctor. In Ben’s present condition, these pals now spent time together playing video games, watching movies, and speaking to each other in the language of Star Wars.

Ben had a quick sense of humor and was an avid talk radio fan. But he was active. In summers, he had attended two Boy Scout camps and 15 years of Muscular Dystrophy Association camps where he swam, rode horses, and played wheelchair hockey. Ben was tenacious. “He never quit trying to do things," says his mother Karen, "and eventually found other ways to accomplish what he wanted to do.” His favorite hobby was cartooning because “he didn’t like to be realistic.” He was a poet.

And he was into music -- from Metallica to classical. “As a toddler,” recalls his mom, “he would jump on his horse whenever his dad would play Tchaikovsky, close his eyes, throw his head back, and jump as hard and high as he could.”

But it was his landspeeder that piloted him into his shared world here, often with his younger brother Luke riding on the back. His pit crew was his dad, Gene, who loved souping up Ben’s wheelchair to be the “coolest wheelchair around.” For beach excursions, Gene rigged flood lights and mods that enabled Ben to go off at night four-wheeling in the sand.

You see, Ben was a Rebel known for his incredible piloting skills. “Ben didn’t have to wait until 16 to start driving," says Peter McHugh, his school principal. "He had his wheelchair and at times liked to go too fast. In spite of a certain amount of diplomatic immunity he’d still get into trouble for ‘running’ in the halls. Sometimes that wheelchair was a bit of a weapon, too. Ben was a very popular student and always had an entourage surrounding him on the playground. He also had a feisty side. To show displeasure or to get classmates’ attention, he’d swing around and bump them or simply back over them. It worked well.”

Just prior to the Hackensack trip, Ben celebrated his eighteenth birthday going to the junior/senior prom with his friend Angela Bludworth.

With classmates they rode the MAX light rail system to dine at a French restaurant and join the rest of the class on the Portland Spirit for a cruise on the Willamette River. Hitting the ship’s dance floor, Ben was “ready to party and dance the night away," says McHugh. He “got his wheelchair moving to the music and danced with the girls.”

The night was capped by Ben’s being crowned King of the Prom -- “I’m sure the only junior ever to be recognized as such.”

But it was his trip to Hackensack that was the most epic voyage of his life. On the launch pad, Make-A-Wish presented him with a limited edition Star Wars Monopoly game, a Darth Vader helmet signed by David Prowse, and Galaxy Club VIP passes for the family. His convention high point was lunch in the VIP lounge with C-3PO himself, Anthony Daniels. Telling him how he could relate to Ben’s disease, Anthony said that while in costume he was unable to conquer such tasks as scratching his own nose or holding his own drink -- he was dependent on others for help. Much moved, Ben recalled how Anthony “had a real understanding about what I deal with on a daily basis.”

Another high point was Ben’s sitting with “Mr. and Mrs. Boba Fett” (Jeremy and Maureen Bulloch) at the Men Behind the Mask Dinner.

On the last day, the family celebrated brother Luke’s thirteenth birthday with a cake presented by Anthony and Jeremy. “Not that many people get a surprise birthday cake from C-3PO and Boba Fett,” Luke later wrote.

After returning to Oregon, Ben gave thumbnail characterizations of us all:

C-3PO, a jolly good friend indeed

Boba Fett, fun-loving and kind

Dak, resurrected from the dead -- a real saint he was

Artoo, small in body, large in spirit, always chatting with the girls

Bib [Fortuna], a real easygoing guy

Mon Mothma, a mother at heart

Lord Vader, Dark Lord of the Sith, wasn’t so evil after all

Chewie, tall and looming, a real huggable guy

And one last thought: “Anthony, if this poem you read/Remember one thing/’Many Bothans died for this.’”

Ben was “a special child,” recalls McHugh, “with gifts of intelligence and unusual insight -- great one-on-one with people, very brave with an extremely strong will to live. He had the heart of a warrior.” Ben identified himself as a “young Rebel knight.” Writing Yoda-like as a 17-year-old, this timeless soul offered, “In this system he is known as Benjamin Fitzgerald. He willingly shares his wisdom with those lucky enough to travel his way through his profound knowledge, and wisdom is not always easily seen. Many times he will tell a story from his past. But you must listen carefully, for there is always a message.”

On the eve of his Hackensack trip, he counseled, “First, seek a wise Jedi Master/Who is fully trained in the ways of the Force… Lastly, you must face your destiny/Against the Dark Side.” In response to the 9/11 tragedy, he wrote, “I am strengthened to rescue others.” At the time, he was faithfully supporting another boy, Lucien, in Congo-Brazzaville through World Vision.

In his last months in this galaxy, he penned, “Soon the battle will be won/and the enemy overcome.” And so it was that on November 15, 2003, aged 24, Ben piloted his landspeeder on his greatest voyage to the next galaxy At his memorial service, singing "I Can Only Imagine," those who remained could only envisage his arrival. So it was Peter McHugh who left a final depiction for the assembled. Ben, he said simply, was a “source of inspiration and courage to him.” And recalling the impact of their thought-provoking talks, this seasoned educator offered how afterwards “he’d walk away a better man.”

John appeared as Dak, Luke Skywalker's back-seater in the Battle of Hoth in The Empire Strikes Back. He also appeared in the film substituting for Jeremy Bullloch as Boba Fett on Bespin when he utters his famous line to Darth Vader, "He's no good to me dead." Follow him on Twitter @tapcaf.