For nearly 50 years, Industrial Light & Magic has been a proving ground for imaginative storytelling, bringing together like-minded individuals from a variety of disciplines to innovate the art of visual effects in filmmaking.

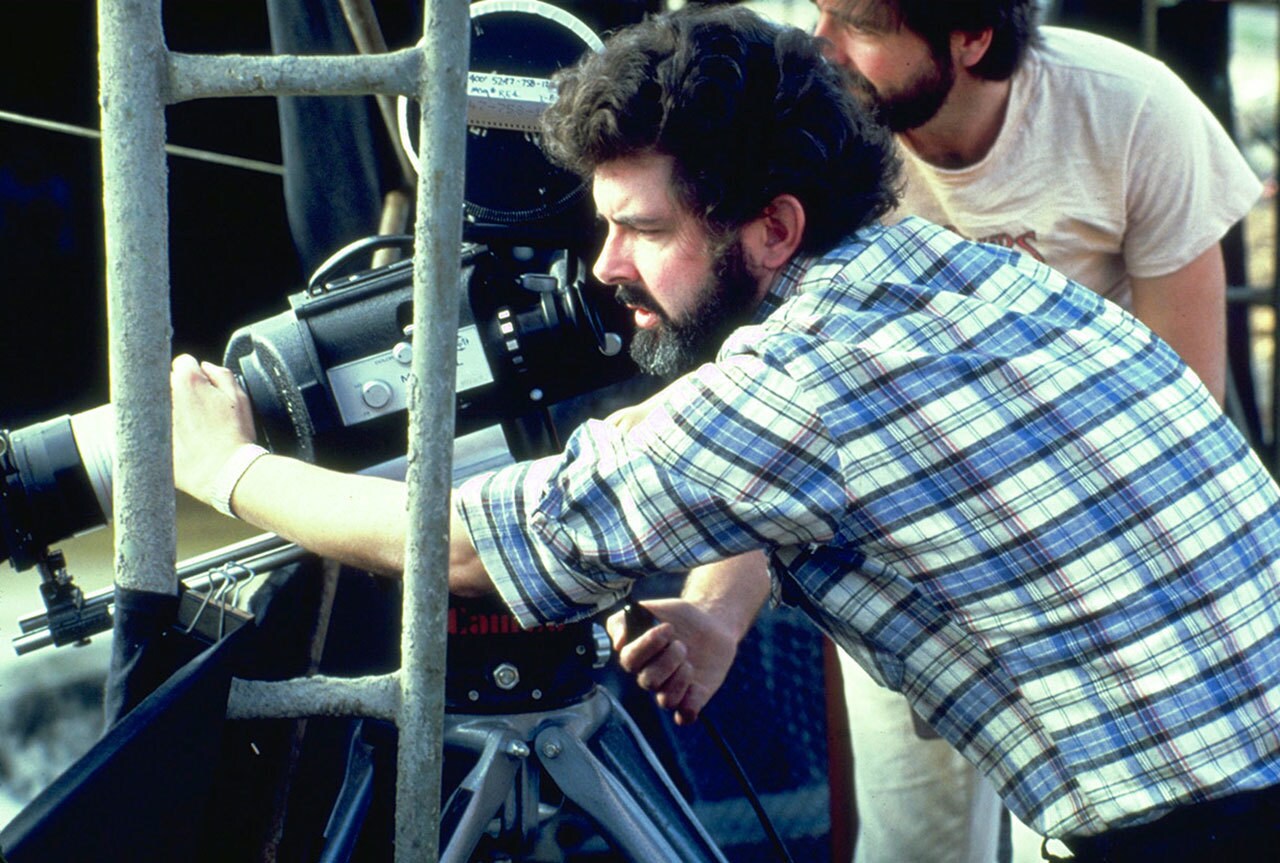

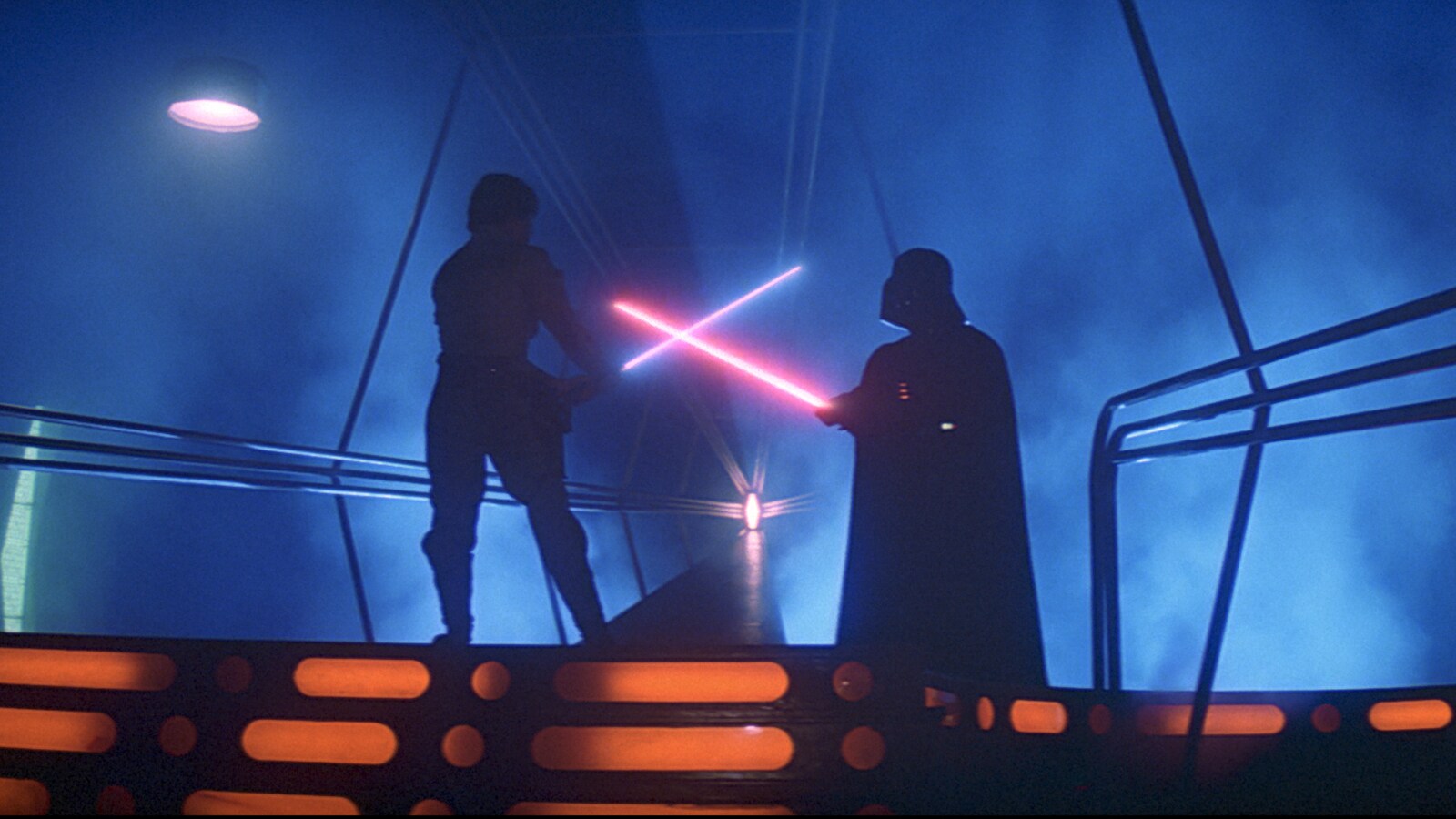

In its infancy, ILM was a place for creating the impossible, where ingenuity was rewarded with results, critical acclaim, and box-office hits that would inspire the next generation of creators.

“It is something that could never happen again,” director and visual effects artist Joe Johnston tells StarWars.com, “All these different elements came together -- some of which had to be created on the spot! They didn't exist, like the motion control. And there were these people, many of whom hadn't worked in film before, but they had a specific skill and a talent to do one thing. It was just something that came together at that moment in time that could never be repeated again. And you know, we were all lucky to have been a part of it.”

For every success, there was always a new problem to tackle in the evolution of the medium, and the pioneers at the heart of ILM’s accomplishments never rested on their laurels. “I just stay curious and when I finish a show, I try to look at the work I had done as obsolete,” adds Dennis Muren, a longtime visual effects supervisor, and now consulting creative director at ILM. “I'm serious about that. It doesn't mean you don't like it. But, is there another place that could have gone that would satisfy me more and maybe the audience would like and the director might be surprised by it? It's searching all the time and being curious.”

To celebrate the release of Light & Magic, the new Disney+ documentary series directed by Lawrence Kasdan tracing the story of ILM from its genesis on the first Star Wars film to its latest advancements with ILM's StageCraft technology, we visited Skywalker Ranch to meet with some of the brilliant minds who helped turn ILM and Skywalker Sound into what they are today.

“A light went on”

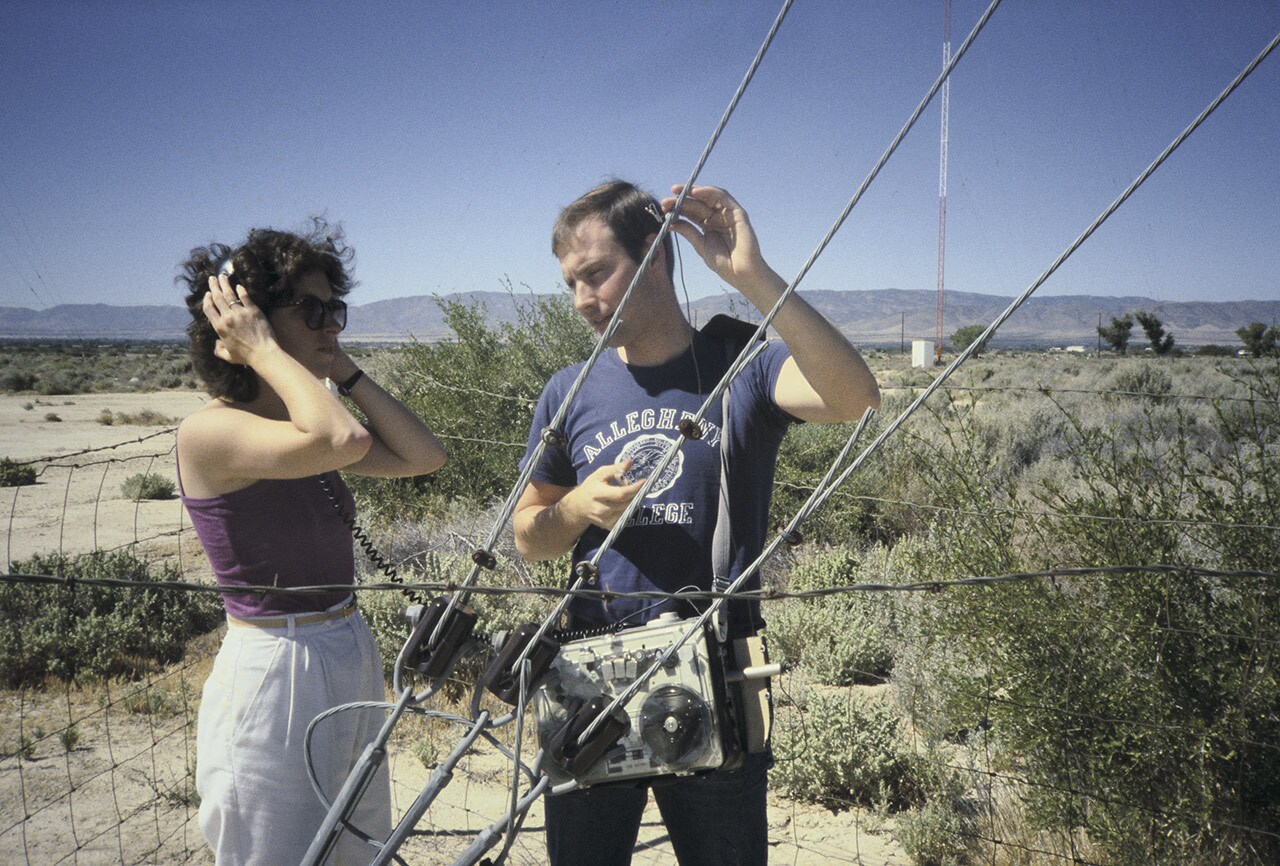

Johnston, Muren, Phil Tippett, and Ben Burtt were among the pioneers of visual effects and sound design hired on in the formative season of ILM and Skywalker Sound.

“I think I was the 11th employee hired,” Johnston recalls, attributing the small staff to his penchant for multitasking in those early days, working on everything from storyboarding to model making. “When Grant McCune in the model shop [asked], ‘Can you paint this?’ I said, ‘Yeah, sure.’ I'd never painted a model like that before, but you figure things out as you go, you make mistakes, and then you learn from the mistakes.”

Although he would go on to become the preeminent sound designer of the Star Wars original trilogy and many other Skywalker Sound projects, Burtt was part of Lucasfilm in those earliest days. The industry was just being created, so most of the people hired on at the time had no experience working on a traditional feature film. “These were not Hollywood veterans who had a way of doing things,” Burtt says. “These were all young people with new ideas, coming from different backgrounds to work on a movie where they'd be learning a lot as they went. And they were asked to invent things and think outside the box. The thing was, they were all outside the box, anyways, to start.”

Muren brought on Tippett -- both would go on to become Academy Award-winning visual effects supervisors -- during the production of Star Wars: A New Hope. “We were very careful on who we hired. I knew a lot of people, but those are the ones that I thought could do the job, that I knew I trusted. And I think that went on in a lot of departments.”

“From different disciplines,” adds Tippett. “A bunch of the guys were not filmmakers at all.”

The longtime friends first worked together at Cascade Pictures, a commercial house where Tippett first got a gig when he was in his late teens. But they met when Muren was showing the special effects reel for his film The Equinox: Journey into the Supernatural. “I was really bowled over by that,” Tippett tells Muren. “You had something to show that was really impressive.”

As a teen, Tippett was fascinated by deconstructing Ray Harryhausen’s stop-motion epics. “I was probably around 14 when 8mm versions of Harryhausen's movies came out. I got one of these little toy things you could pick up at a joke shop that would have 10 seconds of a Laurel and Hardy clip, and I reconfigured that with a couple of tape reels that I somehow fixed up on pencils,” Tippett recalls. “I was able to crank through them one frame at a time and see what was happening frame-by-frame and then pose-to-pose. You just did everything you could to educate yourself. Mentors were particularly important.”

Tippett was part of the crew working on the original cantina sequence, but his gift for sculpting otherworldly beasts and bringing them to life through stop-motion puppetry landed him in the creature shop early on. He still remembers the official hiring meeting. “Jon Berg and I went in for our interview with George [Lucas] to talk about money. Jon's dad had bees and unbeknownst to Jon, he was allergic to bees and one had stung him in his face. So he kind of looked like Quasimodo and so we went in for this interview, you know, to make monsters,” Tippett says with a laugh.

In collaboration with Muren and the ILM team, Tippett and the animation crew would take the Dykstraflex camera system that had made dogfights in space a believable illusion to make tauntauns run across the snowy plains for Star Wars: The Empire Strikes Back. “It took a long time to learn how to even fly one spaceship and get it to look like he was actually flying,” Muren says. “Well, Phil was visiting one day and…”

“It was just like a light went on,” Tippett adds, finishing Muren’s sentence. “Stop-motion animators had been trying to do blurs on their characters and nothing worked. And this was just a no brainer." Dubbed "go-motion," the team merged a model with the motion control system. "It was just a huge leap forward that went on to being a much more sophisticated thing for Dragonslayer and Return of the Jedi.”

“We were trying to do something different, you know?” adds Muren. “We could have done the same stop motion. We could have done all sorts of things to try to blur with Vaseline on the lens, but ILM’s always been trying to go to the next step that is going to make it better.”

Computer animation

Ed Catmull, the co-founder of Pixar, started out wanting to get into animation, inspired by his love for the Disney film Pinocchio, before deciding he wasn’t a good enough artist to achieve his goal. He fortuitously switched his focus in college to computer science and studied at the University of Utah in the 1970s as the potential for augmented reality and virtual reality storytelling was just getting started. “It changed everything,” he says of discovering the combination of art through technology. “That basically reoriented me.”

After graduation, Catmull worked at New York Institute of Technology for a short time. “The problem was that the guy that was funding the program believed that computer scientists were going to replace the artists. Not the right approach,” he says. Luckily, George Lucas had taken an interest in the technological possibilities of animated computer-generated graphics. “George became the only person with credibility in the entire film industry who thought this was going to be important and was willing to fund it,” Catmull recalls. “He made me an offer and I jumped at it. So then we started to build a group, the Lucasfilm Computer Division.”

Together, they would create the basis for RenderMan technology that would later help launch Pixar Animation Studios and computer-enhanced animated storytelling moving forward. “ILM consisted of the people who were the very best in the world at the optical mechanical chemical processes. It was really pretty amazing. But what was cool about them was that they were fixated on what they needed to get on film, not how they worked,” Catmull says. “They were neutral towards computers; they weren't opposed to it.”

The atmosphere at ILM was one of unfettered excitement coupled with tremendous pressure. “It was a very high-spirited time,” Burtt says. “ILM was a place where everyone was in shorts; it was like a beach community. It was definitely informal. In fact, I was a little surprised at first….But there was always a stress underneath all of that because a huge goal needed to be attained and the technology to do it was just being invented day by day.”

“We got better and better at what we were doing. We figured it out, we had a process,” Johnston adds. “In the beginning, it was just experimentation. But we never really knew what the movie was going to be, you know? We didn't even see [Star Wars] complete until the premiere. We had seen a rough cut with no visual effects.”

Johnston left in 1985, with plans to travel using the money he’d saved up from working at ILM for a decade. “I never wanted to be in the film industry,” he says. “I was an industrial designer when I got the job working at ILM.” But Lucas had other ideas. “When I left, I told George [Lucas] I just had enough. ‘I don't want to see another visual effect!’ I was going to travel and he said, ‘Wouldn't you rather go to film school?’ And I remember this distinctly. I said, ‘George, I feel like I've been at film school for 10 years.’” With a grant to pay for his education at University of Southern California, Johnston took Lucas up on his offer, which launched his career by helping him land the gig directing Honey, I Shrunk the Kids, among other films, many of which would include visual effects created by ILM.

“Don’t be afraid of the future”

The educational bedrock of ILM continued into the next generation of filmmakers who came through the visual effects house’s doors.

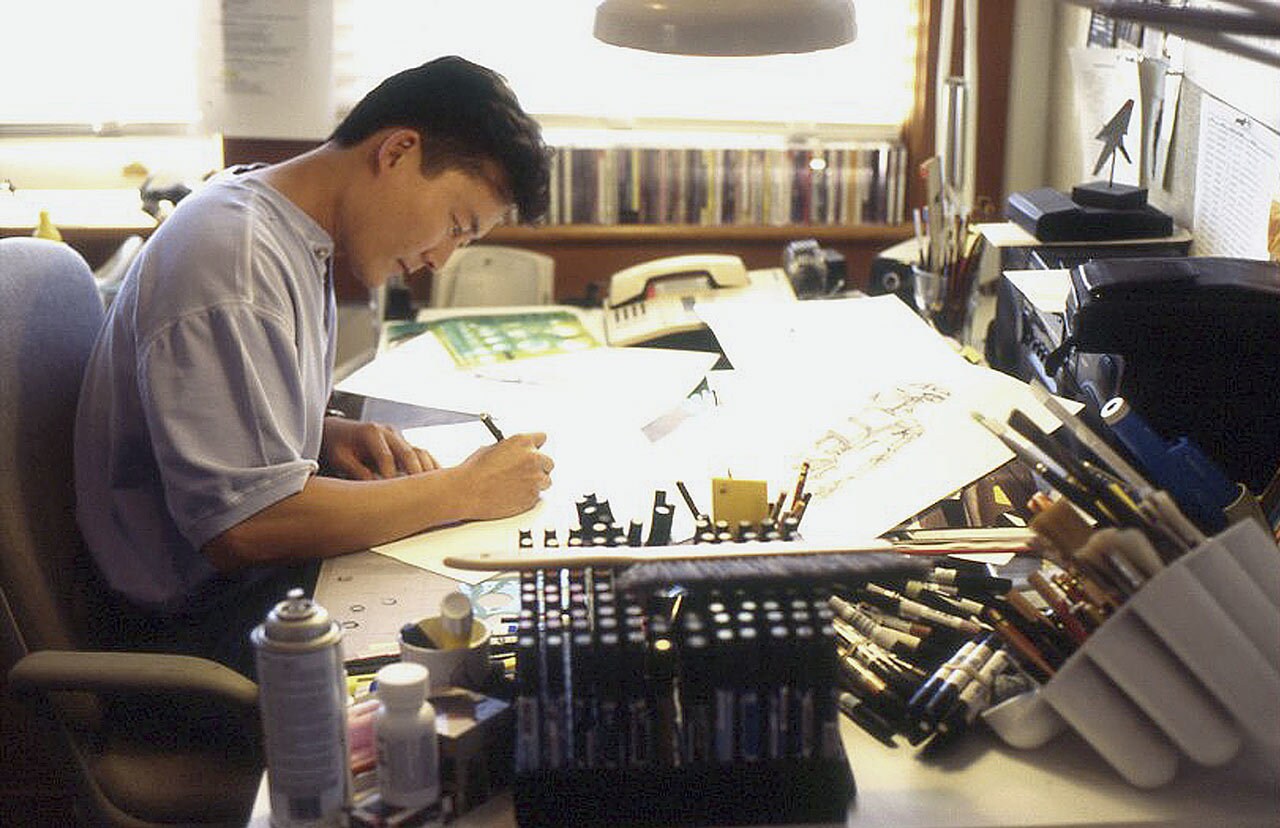

For many, Star Wars and other ILM films had propelled their interest in filmmaking as a medium. “The film itself captivated me,” says Doug Chiang, now Lucasfilm’s Vice President and Executive Creative Director in the art department. “It really kind of created this other world in such an immersive way that I really want to learn more about it and experience it. Then the following year, when The Making of [Star Wars] film came out on television, that completely transformed me.”

Chiang studied film at the University of California, Los Angeles, and was driven to find a path to ILM and Lucasfilm in Marin County. But even with the formal training in film, there was no clear trajectory for the young artist and designer. “It was really hard. I looked at everybody else in terms of the making of documentaries -- Ralph McQuarrie and Joe Johnston -- and there wasn't a very defined path. It was all fortuitous.”

Luckily for Chiang, while working in production in LA, he got a lead on a three-week project as an artist at ILM. “It was a really short project, but it was my chance, my foot in the door. And I remember when I got that opportunity, I packed up everything, got out of my apartment, and drove north, hoping that those three weeks would lead into something else. I had no guarantee that I was going to be at ILM for longer than that, but I had to do it because this was a chance to fulfill my dream.”

Encountering the legends of ILM was life-changing for the young artist who had so long studied their work. “I remember my first day vividly walking through ILM,” he says. “There was this hallway where all the show storyboards were put up, where they would have meetings. I went past the reception to walk through there to go to the art department and Dennis Muren walked right by. And, of course, I knew him because I've seen his picture a hundred times, but just seeing him in person was just mind blowing. And then Lorne Peterson and Ken Ralston. I felt like I was in Oz or some fanciful place in my imagination where all my heroes from childhood were there in person.”

John Goodson had a similar experience. He was first captivated by the visual effects of Star Trek and Lost in Space as a child. At the age of three, he recalls seeing the Jupiter 2 landing, full-screen, a seemingly impossible sequence. “I was so fascinated by that. I was like, ‘If I get the TV open, I could get this thing out of it.’” Seeing Star Wars a few years later lent his fascination more focus. “I started writing letters to Lucasfilm,” he says, asking for a job. “And they'd write me back and say, ‘Don't write us anymore. Your letter’s on file.’”

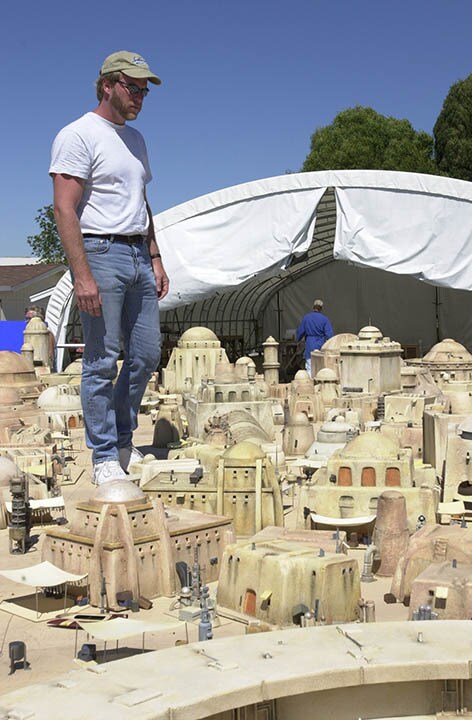

But Goodson ultimately landed a gig in the model shop in 1988 -- he would later stumble across his letters filed away in company storage -- before landing in the computer graphics department.

It was a time of great strides in technological advancements, a boon for digital production that was, admittedly, daunting for those who worked in more practical effects and worried that their craft was about to become extinct -- ironically as a result of visual effects achievements created to bring dinosaurs to life for Jurassic Park. “The model shop knew this was happening,” Goodson says. “That film had one miniature in it: a crushed Ford Explorer. And that was the only model. It was like, ‘Oh, the writing is big on the wall now.’”

But Lucas, always looking to the horizon of possibility, saw nothing but potential. “I asked George if we were going to get rid of the model shop and he said, ‘Don't be afraid of the future,’” Goodson recalls.

In a few short years in the early 1990s, the industry took a staggering leap forward, starting with the release of Terminator II in 1991, with captivating effects from ILM, followed by Pixar’s deal to make Toy Story, and capping off with the success of Jurassic Park’s groundbreaking feat. “Jurassic Park had about seven minutes of dinosaur animation. It was so impactful that most people thought a lot of it was filled with it,” Catmull says. Computer graphics went from “’It's completely irrelevant’ to ‘It's changed everything!’” Yet those inside the business knew it was actually the culmination of 20 years of advancement, growth, and computer speeds finally catching up to the imagination of the filmmakers and their crews.

“That shared rebel spirit”

In the years since, ILM has continued to push the envelope. Each new achievement has been built upon the innovations of the pioneers who came before, using the previous success as a framework for the future. And yet, new technologies have not replaced classic techniques, they’ve only served to enhance them.

Goodson is still making models for Lucasfilm and ILM, recently working on the Razor Crest and Moff Gideon’s light cruiser for The Mandalorian. “For me again, it's kind of a full circle thing,” Goodson says. And Tippett continues to contribute the practical magic of stop-motion animation, recently bringing the mobile loading gantry to life in the second season of The Mandalorian, as well as the skittering B’omarr monk in The Book of Boba Fett.

ILM has expanded to encompass five studio locations around the world. When Janet Lewin started her career with the company nearly 30 years ago as a temp worker in the purchasing department, ILM had 130 employees in the Kerner building in San Rafael. “Now we have over 3,000,” she says. “I think it's really inspiring to look back on our legacy and realize what an impact these amazing geniuses -- many of whom still work at ILM -- have made on films and iconic imagery.” Both Lewin, now Senior Vice President of Lucasfilm Visual Effects and General Manager of Industrial Light & Magic, and Lynwen Brennan, General Manager and Executive Vice President of Lucasfilm, count ILM films among their inspiration to get into the business. Lewin was spurred by seeing Terminator II. “The early films in my childhood -- Star Wars and E.T. -- those are the things that sparked my love of film, but they didn't really make me want to get into the industry or even think that was possible for me growing up in Wales,” Brennan adds. “The film that really did it for me and made me think ‘I have got to work at ILM one day’ was Jurassic Park.”

Most recently, the development of ILM StageCraft technology has allowed in-camera visual effects capture like never before. “At Lucasfilm and ILM, our mantra is that story drives everything,” Lewin says. “We never invest in technology unless it's in support of a filmmaker's vision. One of the really cool aspects of StageCraft and really about ILM is: it's not the tool. It's the people; it's the craft.”

“They've got that shared rebel spirit,” adds Brennan.

And simply stunning an audience isn’t the goal; visual effects only work if they’re in service to the story, Johnston adds. “I was always looking for something that was not so visual effects heavy because I wanted to prove to myself that I could tell a story that didn't need visual effects to help it along. But, you know, visual effects is just a tool to help you tell the story. Because you can put anything on the screen that you want to, that doesn't mean that you should. Everything that goes through that lens needs to be in the service of telling the story.”

For The Mandalorian, Jon Favreau had an idea for a Star Wars live-action series with the planet-hopping scope of a film and the budget and schedule constraints of a TV show. “I love those moments when you are in a room going, ‘Well, how on earth are we going to do that?’ But having this full confidence that we will figure it out," Brennan says. "ILM StageCraft is a great example. We had signed up to do it on a deadline while not having any clue whether we could do it. And, you know, you get that euphoria of knowing you pulled it off.”

Lewin still remembers the moment vividly. ILM had built a tiny volume, to test what would ultimately become the StageCraft platform on a smaller scale, a stage enveloped by LED screens with hi-resolution imagery from a studio location. They brought in the shiny metal costume for Din Djarin to see if the theoretical solution would work. “And the reflections, the realism, the interactive light,” Lewin says. As special effects supervisor Richard Bluff has said, Academy Award-winning filmmaker James Cameron came to have a look and couldn’t believe his eyes. “If we could fool Jim Cameron, then we knew we were onto something,” Lewin says.

Watch portions of the interviews at Skywalker Ranch on the latest two episodes of This Week! In Star Wars below!