It may be hard to believe, but some good actually came from the Empire’s second Death Star.

For Star Wars: Return of the Jedi, Industrial Light & Magic had built a huge model of the new technological terror’s surface — “two times larger than a tennis court,” legendary ILM general manager Thomas G. Smith tells StarWars.com — and it was too large to be stored after filming. On the orders of George Lucas himself, who usually saved and preserved every model from the Star Wars films, it was to be trashed. So, some ILMers took the model apart, rented some trucks, and drove the pieces to a nearby garbage dump. But someone actually wanted to save the Death Star.

“My son was working at summer employment there, and he saw all these pieces going into the dump and he thought, ‘No, no, no,’” Smith says. “‘Some of that stuff looks good!’” Smith’s son saved a box of pieces for himself and held onto it for years — ultimately putting it to ironically good use.

“Later I told him he was a fool. ‘Get rid of ‘em! That’s garbage, throw it away!’ And when his daughter went to college, he was able to fund part of her college expenses by selling these fragments of the broken Death Star.”

Smith laughs, recounting the story to StarWars.com in a conversation celebrating the 40th anniversary of Return of the Jedi. His journey to Star Wars began at Northwestern University, where he graduated in 1960 with a degree in film, followed by a Fulbright Scholarship to study at the Institute for Higher Studies of Film in Paris. After a three-year stint in the US Air Force, Smith joined Encyclopedia Britannica, where he made over 60 educational films including 1977’s Solar System, an innovative work that won several awards and impressed George Lucas. Lucas recruited Smith to join ILM during production of Star Wars: The Empire Strikes Back in 1979; by the time of Return of the Jedi, Smith had been named general manager, overseeing all visual effects. “We had 300 employees and I was responsible for all the stuff that a general manager would do,” Smith says. “Make sure that everything's being done, all the work is being done, assigned who did what, and dealt with the union and dealt with the filmmakers to ease their concerns.”

The final film in the original Star Wars trilogy, Return of the Jedi would be bigger than anything Smith had been involved with previously, to the tune of 900 effects shots. “Nine hundred shots is a hell of a lot of work. And each shot had an average of, let's say, five elements. So that means, you know, about 4,000 camera setups,” Smith says. “Well, I knew it was a real challenge, but I knew we could do it. And if we couldn't do it, we'd try something else.”

An example of the latter ethos would be the iconic rancor sequence. The original idea was to shoot the rancor Godzilla-style, with a performer in a suit. When the results were lackluster, the idea came about to use a rod puppet. “We knew it was going to be hard from the beginning, but Phil Tippett had a responsibility on that one," he says. "Phil had terrific patience.”

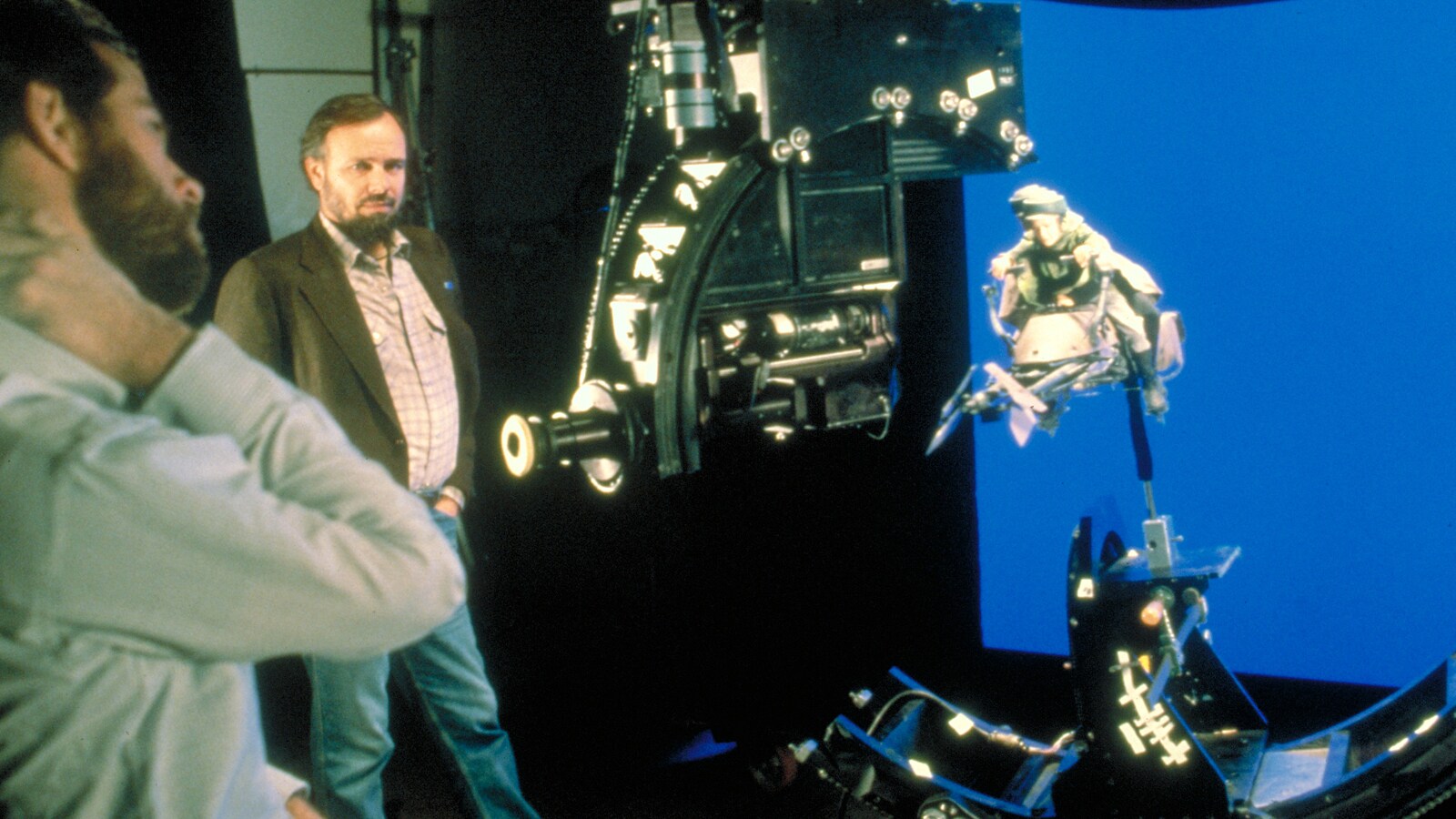

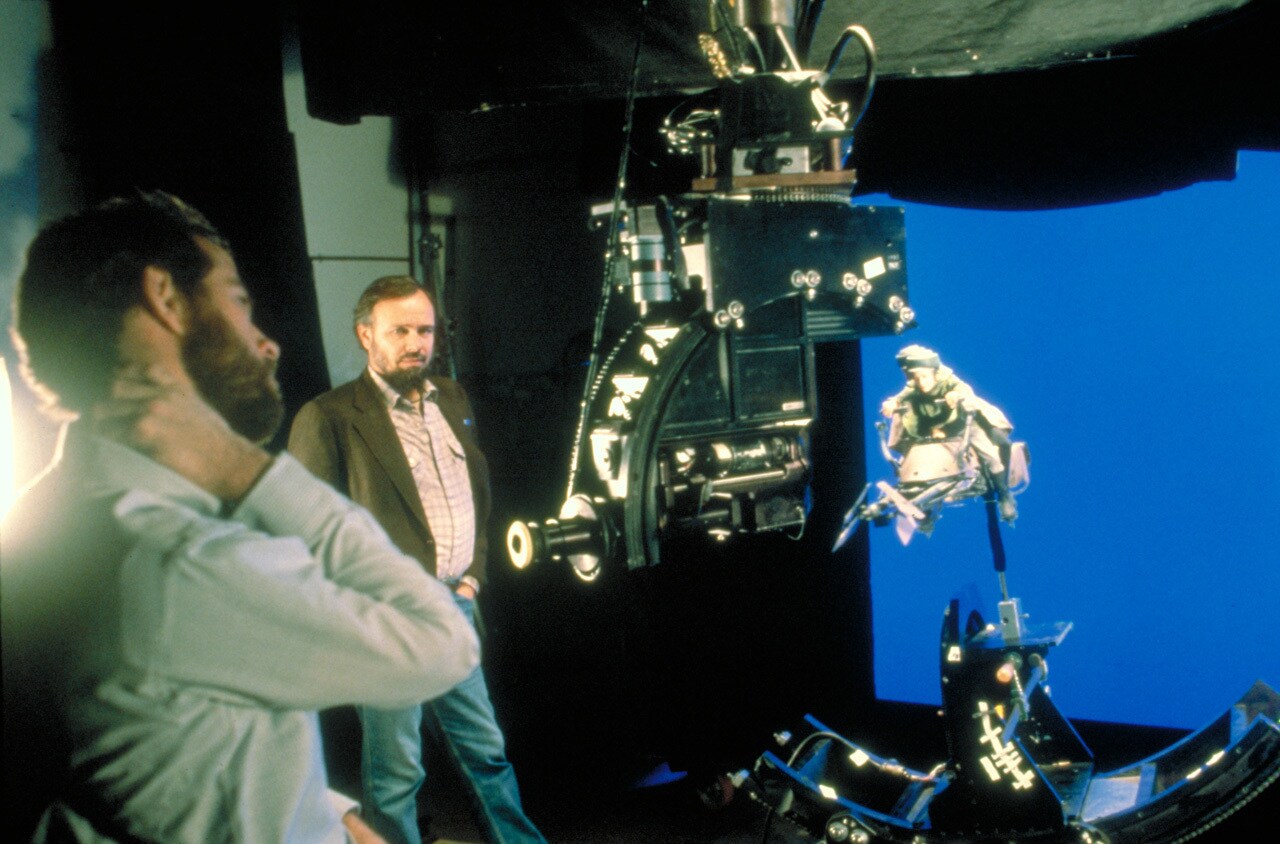

Smith credits Tippett and ILM’s other wizards, all with specific talents, in achieving Jedi’s amazing effects. “I had shot documentary films from about the age of 25 until I came to ILM, so I understood everything. We would sit down at the conference table and discuss these things, how they would be done, who would do them, and so forth. But the people there were very talented and didn't require any great advice from me, because they were very good. Each one was more talented in certain areas. Dennis Muren was a great cameraman, lighting man, visualizer. He shot the effects for E.T. and it's that kind of sensibility. Richard Edlund was a genius at designing mechanical things. He could do drawings that would go to a machine shop and they would make it. He made one of our cameras and he did Poltergeist, at the same time that Dennis was doing E.T. You can see the difference in a different kind of a mind at work. And Ken Ralston was a great animator, as was Phil Tippett. So, they all understood very much what they were doing.” Still, as general manager, Smith notes that he would sometimes have to be the mediator when tensions would flare, even among friends. And for that, he had his own special effects trick, as it were: When he would host the ILM morning meeting, there was one rule.

“Come into my office, but nobody could sit down. That way the meeting was kept short. Nobody got comfortable.”

Smith recalls meeting director Richard Marquand only once. “I met Richard Marquand when he came to interview for the job. George interviewed him in my office and I met him. He was a very nice fellow. And I just sort of sat there during the job interview, you know," Smith says with a chuckle. "But he was a very nice guy." Marquand, Smith says, dealt more with the actors and photography; Lucas, on the other hand, was heavily involved with the effects. How often did the Star Wars creator stop by to see what ILM was doing? “Every day. The editing room was a hundred yards away from ILM. We had a big industrial building, which was ours, and then there was a driveway. And across the driveway was another building. Inside that building, that's where George was. So, every morning we would get our dailies — work from the previous day — and we would have this screening. George would come in, sit down and look at it, comment on everything that he saw, and then sometimes take a walk to look at something, some question we had about something. Generally speaking, he was, most of the time, more accepting with the shots than we were. The cameraman would say, ‘Oh, I got a little thing there wrong.’ George would say, ‘They'll never see it,’ or ‘Put down that it could be better and we'll do it at the end if we've got time.’ Well, we never had time.”

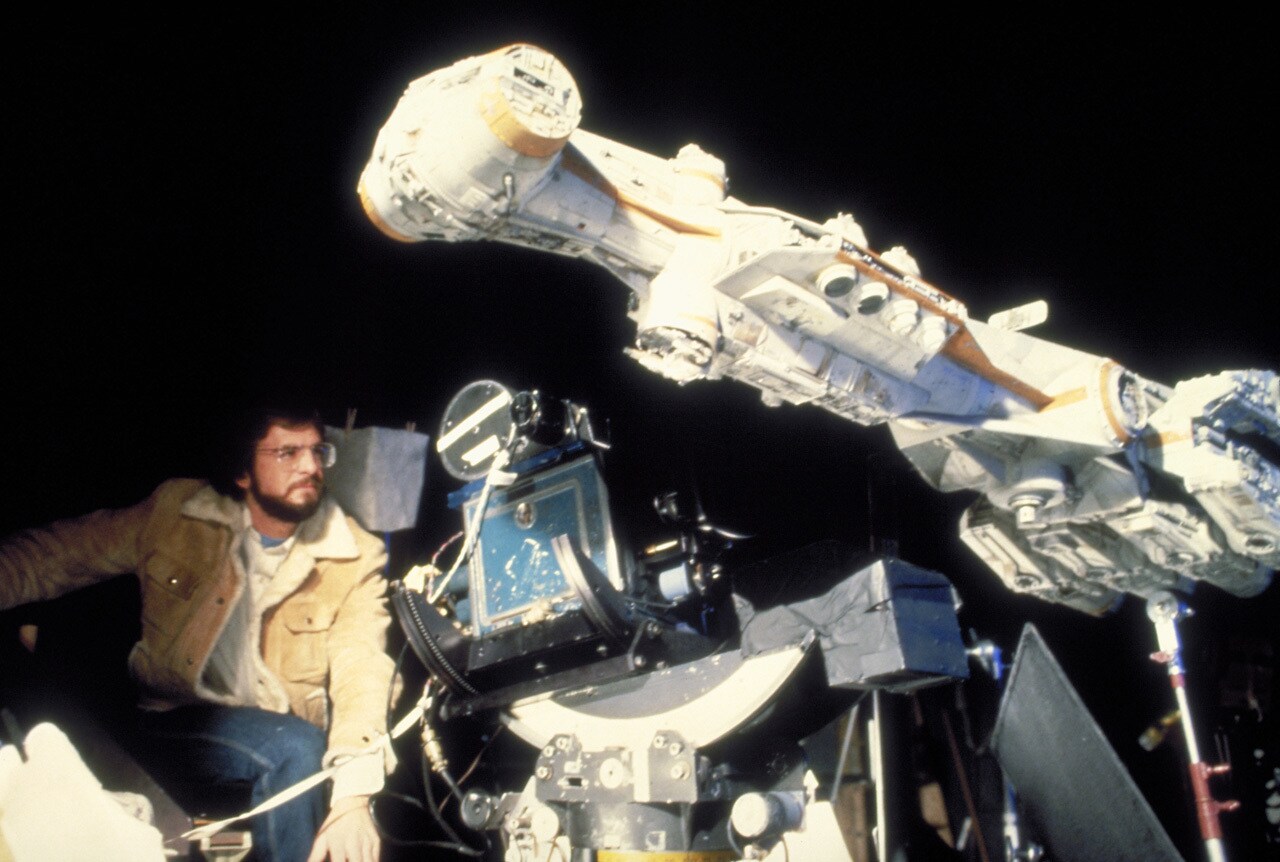

Still, even with time and budget constraints, Smith and ILM created classic effects sequences for Return of the Jedi, including the rancor, the speeder bike chase, and the climactic attack on the second Death Star, which featured more — and faster — ships than ever before. “There were scenes where there were a tremendous number of spaceships in one shot. Each spaceship was an individual model," Smith says. "I have to remind people, who nowadays work with digital, that everything was physical.”

A famous Easter egg in the final space battle is that one of the fighters isn’t a ship at all — it’s a sneaker belonging to Ken Ralston, visual effects supervisor. When producer Howard Kazanjian asked if he could keep a model from the sequence, Smith knew just the one to send him. “‘Sure. Here.’ So we got a nice plastic case and a plaque, and put the shoe in it.”

Forty years later, Smith remains proud of Jedi, both in terms of its visual effects and its place in the original trilogy. “I think it's one of the major Star Wars series films. George sort of lost me when he got deep into the digital creatures. It was maybe because I'm so old. But to me, the first three Star Wars films are the treasure.”