Ben Burtt and Randy Thom are two legends in the world of sound. Burtt is, of course, known for his early work in shaping the Star Wars galaxy, from the hum of the lightsaber to the beeps of R2-D2. Thom began his journey at Skywalker Sound (then known as Sprocket Systems) on Star Wars: The Empire Strikes Back, and is still working at the company, with his most recent project as sound designer for this year’s megahit, The Super Mario Bros. Movie.

Burtt (as sound designer) and Thom (as re-recording mixer) worked together on Star Wars: Return of the Jedi, which, at the time, was the most sonically ambitious Star Wars project ever, earning them both an Academy Award nomination. The crafting of the Ewok dialect, the Sarlacc’s squeal, and the Emperor’s Force lightning all presented unique challenges for the young sound team.

To mark the film’s 40th anniversary, StarWars.com caught up with these two friends, who reminisced about their groundbreaking work from four decades ago, as well as their favorite sounds and memories from Return of the Jedi.

StarWars.com: Return of the Jedi was the first time that the entire sound process was controlled by your team at Sprockets, including sound mixing, foley, and dialogue cutting. How did you set your team up for success?

Ben Burtt: We felt we were up to speed after Empire because, for me, the first Star Wars movie was a learning process. On Empire, we did all the post-production up north, at Sprocket Systems in San Anselmo. We could do everything, including some pre-mixing of sound effects, but it wasn't until Jedi that we built a new facility over on the far side of San Rafael, in the complex next to Industrial Light & Magic. We finally had our own mix stage, and the responsibility of doing the final mix.

It was a huge difference for everybody. We could now stay local, with our whole editorial team in the next room. My team had to take turns cramming into a very small mixing board that was really made for one person. But we managed to do it.

Randy Thom: It was a tight fit. George [Lucas]'s vision for Sprocket Systems, as well as the entirety of Lucasfilm, had been to make it as much like film school as he could, where everybody does a little bit of everything and nobody's too worried about staying strictly to their job description. It was an environment that all of us thrived in because we were all interested in learning as much as we can about the craft.

Ben Burtt: It was a nice thing for me because I could have all kinds of assignments. I was free to go out and record things, then come back to editorial to work and follow through with mixing. Sometimes I could visit the set and have a voice there, as well.

StarWars.com: When you went to set, were you able to at least attempt to control the various sound impediments?

Randy Thom: Film sets are notoriously noisy places. There are often fans operating, creating a sense of wind in the actor's hair, as well as all kinds of other smoke and special effects machines going on in the background. And, as often as you ask the crew to be quiet, there are going to be people who think it's okay to whisper. Of course, the microphone picks all that up and so it's just hell to record any usable sound.

David Parker and I went to Yuma, Arizona [exterior filming location for Tatooine], and the Smith River area in far northern California [used as the forest of Endor] to capture the location sound during the shooting. In fact, it was around Smith River where I first uttered the phrase, “May the fourth be with you.”

Ben Burtt: He told me that and I believe him. He can lay claim to that whole concept. That was very good, Randy.

Randy Thom: That's my claim, yeah.

Ben Burtt: I had high expectations that, if I went to the set, I would get perfect dialogue and coverage of whatever sound effects might be there. A lot of that was fruitless.

For me, there’s the now-famous scene of Luke and Leia in the Ewok village, where they’re talking intimately up on the suspended bridge. I would guess it’s about a three-minute scene. I was there that day, and for some reason I had the confidence to be the boom operator. I said, “I'll hold the microphone out over the set.” And, because it was going to be just a nice, quiet dialogue scene, I was going to get this perfectly.

It was a long scene, and I was stuffed in with the crew. I was holding a fishing pole above them, out of frame. And the scene goes on and on. I had a bad grip on the pole and my arms were starting to fail. It was heavy and I could see the mic coming closer and closer to falling into frame, and then it was going to hit Carrie [Fisher] on the forehead. I was in agony. I didn't realize that, after a few minutes, holding a boom mic was going to be an isometric test of my strength. Fortunately, I didn't hit her. But the set was noisy: someone's watch went off during one take, the bubbling dry ice was just few feet away, creating this fog. It was very difficult.

So, I didn't do any other boom operating. I went back and just did sound effects.

StarWars.com: Across the board, Jedi is an escalation of effects, both visual and sound. How did you make sure that you didn’t drown yourself out?

Ben Burtt: Fortunately for us, George Lucas’ process starts months and months before shooting. Once there was even a treatment for the movie, he started talking about sound. So, I got assignments right away. George had ideas, so we were all going out to record things. We laid out a highly structured list of jobs, since there were about a thousand new sound design projects in the film, even though we already had a foundation from the previous movies of the Millennium Falcon, lightsabers, and everything.

Randy Thom: It was very rare, basically unheard of in Hollywood, to have sound involved that early on. But Ben and George established that workflow on the first Star Wars film and then we all really pushed it even further on Jedi, where we had a whole team working very early on. We went on to apply that approach to most of the projects that we've worked on at Skywalker Sound since then, whether they were Lucasfilm movies or not.

We broke quite a lot of new ground in terms of establishing how useful it can be for us to play with sound design very early in the process.

Ben Burtt: You gain confidence in the material. For us, it’s very well organized: everything has a code number, a name, a description. Editors then get specific assignments and a batch of material, which has already been, in a sense, approved. They can work creatively within that, using that material and applying it, adding their own ideas to improve it. I think that's the difference, between what we saw in Hollywood, compared to Sprockets, where we wanted to really have a control of everything and meet our deadlines.

StarWars.com: As you mentioned, more than ever, non-human characters played a huge role in Jedi. How did you make sure the alien languages and sounds were realistic?

Ben Burtt: We tried to make it fun. We discovered that, if you can get some enjoyment in the creative process, it will come out in the movie in terms of the performances and the sounds. It will entertain the audience.

Creating languages is always the hardest thing for me, because, with any kind of language, the audience is already very acute to analyzing vocal sounds. Who is speaking? Is it a man or a woman? Is it something else? You’re trying to make all these languages derived from human performances, so you must use some clever trickery to avoid judgement from the audience to where it all came from. You just want them to believe what's happening on screen.

StarWars.com: How did you begin to approach crafting these languages?

Ben Burtt: Actually, the very first thing that I did on the first day of Jedi was talking to George about the Ewok language, their personalities and what they might sound like, as well as, musically, what they were doing at the end of the movie when they had a victory celebration. John Williams was brought in early on for a meeting in my San Anselmo studio to listen to different music that George had picked out.

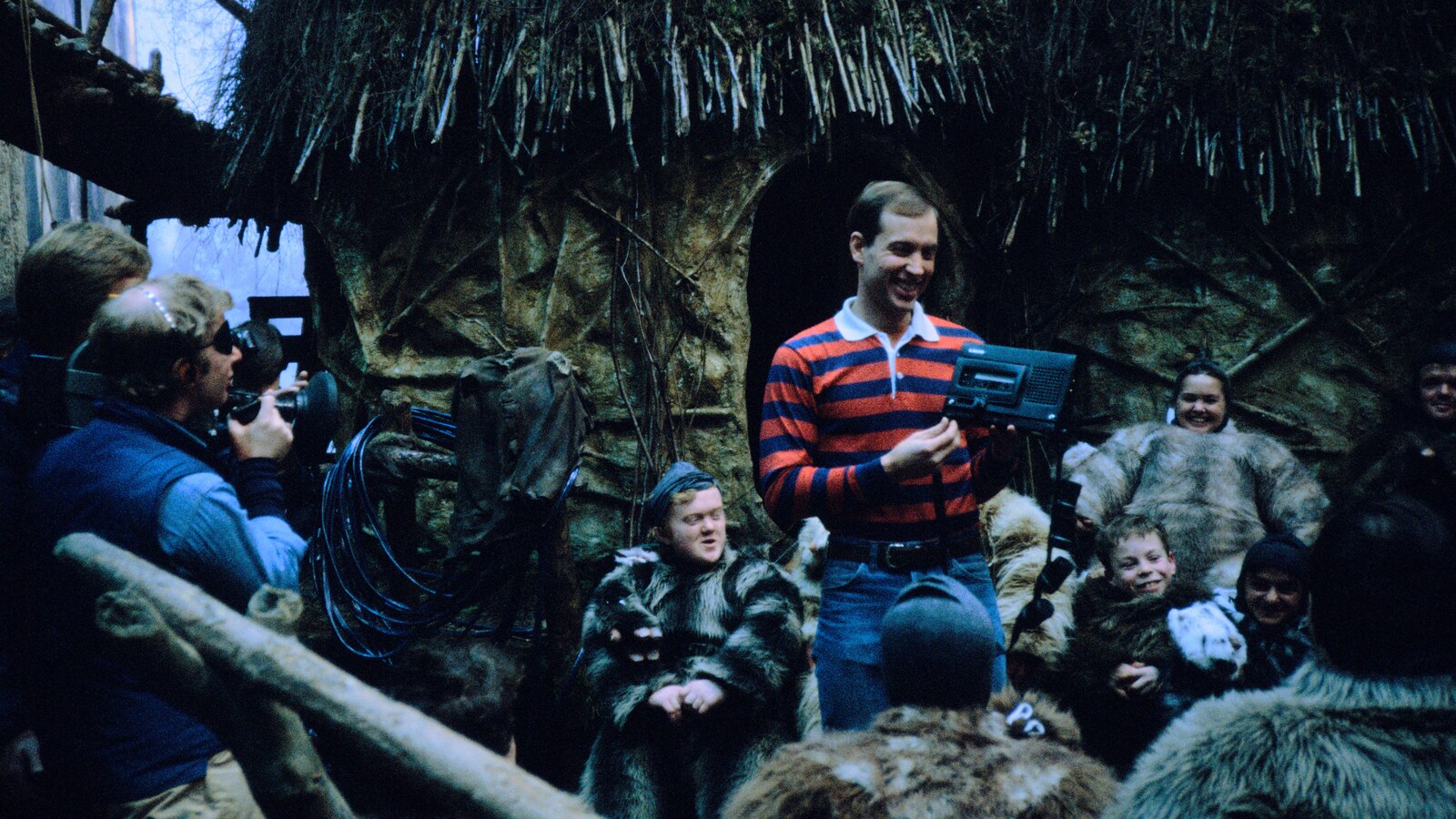

We talked a lot because, like for Chewbacca in the very first film, some kind of language needed to be worked out prior to filming, so that the Ewok performers would have a guide to go by. They needed inspiration, and the mouth movements of their masks and their body language had to be something that we could sync interesting sound up with.

Above: "Ewokese" effects from Return of the Jedi

StarWars.com: What exactly was “Ewokese” comprised of?

Ben Burtt: The Ewok language was, essentially, a mixing bowl of different things. We wanted to at least base it on some known language because, if you start with a language that really exists, it has a whole history that extends its range. If I just made things up, I would only be drawing from my experience speaking English.

We initially started by auditioning people who were Tibetan, Chinese, or Mongolian, and so on. We found a couple people that ran a little gift shop in the Embarcadero, a father and son that we brought out to get samples of their native language. Eventually they brought us a relative of theirs, who had just immigrated. She was probably nearing 80 and did not speak any English, only Kalmuck.

We brought her into the studio, as we had with other people. Even with amateurs, I always wanted to get a lot of emotion out of them. I would ask them to just pretend that they were telling bedtime stories to their children, storybook kinds of simple stories, in order to get them in a relaxed state.

And so that's what we did to get her to talk, to ramble on, to tell stories, to get emotional and to laugh. She was really great and gave us some great material. Her name was Kosi Unkov. I have no idea whether anyone understood it, because a lot of it is used in the movie.

What we were really looking for was an interesting sounding voice. There was an elderly woman from China, with a scratchy, deep pitched voice. When you listened to her and did a little speed adjustment on her recordings, you couldn't tell if the speaker was male or female. It was always an important thing for us to make the Ewok language genderless, so that when it was edited to fit the performance of an Ewok, people wouldn't identify it as a specific English-speaking person. That illusion was important in getting any alien voice to succeed.

Above: Ewok battle cry effects from Return of the Jedi

Randy Thom: We certainly related to the Ewoks as if they were human, but in a sense, they are more animal than they are human. One of the interesting things about doing voices for creatures is that filmmakers will often ask us to come up with, let’s say, a female vocalization for a dinosaur. And there’s really is no such thing. Even though you know members of a given species can no doubt recognize their species, humans cannot tell by sound whether they are hearing a female lion or a male lion, a male squirrel or a female squirrel. That’s another reason why it would have been kind of wrongheaded to try to have female Ewoks and male Ewoks. I think it wouldn't have rung true somehow.

Ben Burtt: Just looking at my old logbooks of the different people we recorded, there are probably a dozen here: some people were amateurs that we found locally that just had a good sounding, genderless voice. We would then give them phonetic material to read and just coach them along in the studio. We might get, you know, five or six interesting bits, and we would assign that to a certain character. We would build them into a crowd, or into war cries, or laughter.

Other real animal sounds were derived from chimpanzees and tigers. I can see here that we had some chimp laughter and a baby lynx. It’s really a grab bag of samples of anything that interested us, any kind of sound that had an emotional appeal or meaning to it. You could always play it backwards or slowed down or sped up and fit it in there.

Above: "Huttese" effects from Return of the Jedi

StarWars.com: What was the process of creating the noises and dialect for Jabba the Hutt?

Ben Burtt: Jabba spoke Huttese, which was a made-up language that I based on the Peruvian-Incan dialect, Quechua. We had heard Quechua language tapes back on the first movie, and I just liked the sound and rhythm of it. We listened to a lot of examples of it and then we would either attempt to imitate it, or we would get Larry Ward to do it.

Larry was a linguistics professor at UC Berkeley, who had a unique ability to perfectly mimic other languages. He would “speak” German or Italian but he wouldn’t actually really speak the language, just use all the phonemes to fool you. It was just a funny double-talk kind of process.

I would play things for Larry or write down phonetic sounds that I liked. He would play with it, we'd record it and pitch him around. He had been the voice of Greedo in the first Star Wars, so we brought him in for Jabba the Hutt and gave him a lot of lines. Some lines George wrote, some I wrote. We then took his voice and slowed it down, so it was deeper. At the time, we had some ability to pitch lower electronically, and then we added a subwoofer to the bass to make it seem solid and heavy.

Jabba’s voice was then augmented with a lot of cheese casserole that my wife makes. I would take a bowl of it, work it with my hands, and make a kind of a slurpy sound. We tried to put pieces of that into all of Jabba’s movement, so he sounded liquid-y and squishy as it went along.

Above: "Oh no! The rancor!" effects from Return of the Jedi

StarWars.com: What about the rancor’s roar? What sounds made that?

Ben Burtt: The rancor was mostly made with a snarling dog.

We took those kinds of sounds and slowed them down, so we get more mass into them. We also recorded an elephant over at the Oakland Zoo. We had those bellowing sounds that ended up somewhere in there, and it all became the rancor.

StarWars.com: Jedi has the most “diegetic” music of any of the first three Star Wars films. Was there any collaboration with John Williams on that aspect of the film?

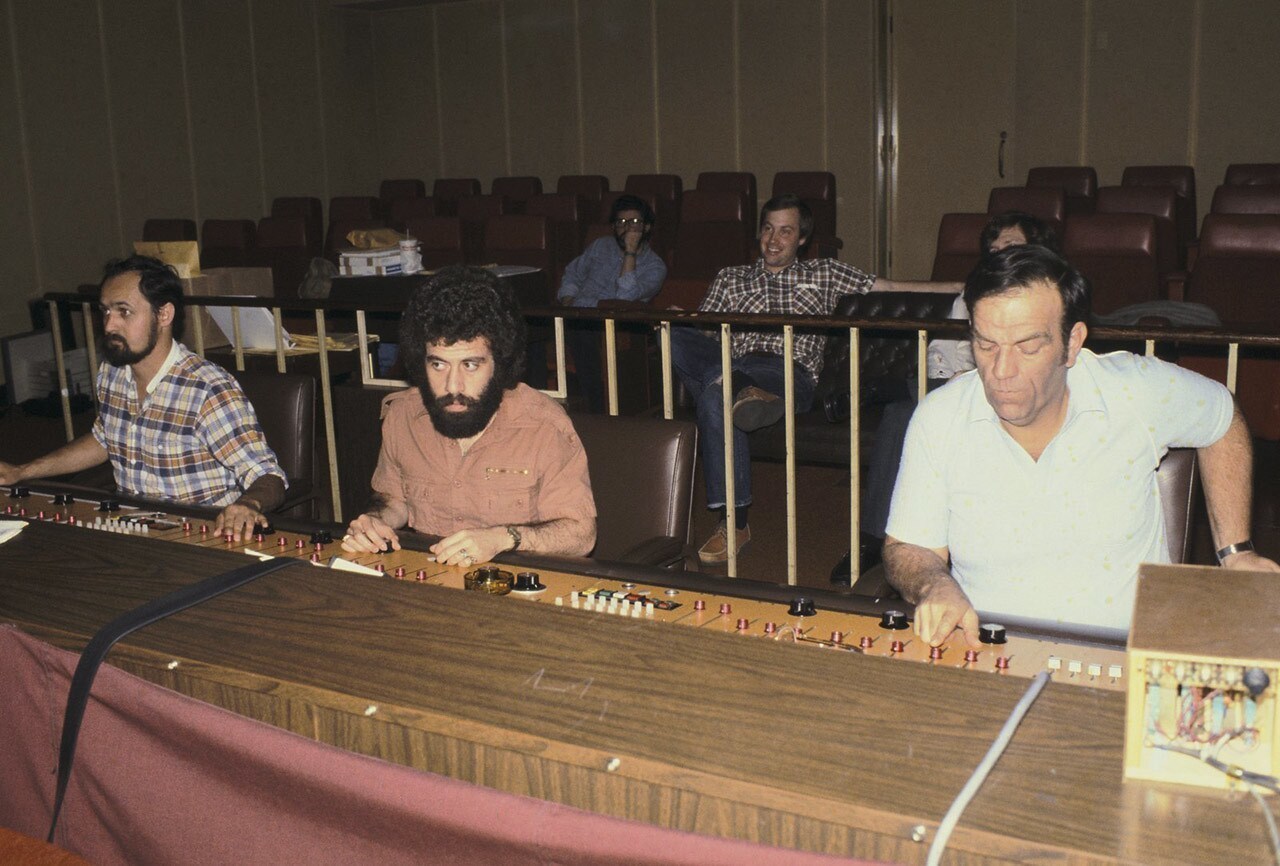

Randy Thom: I remember one day during the final mix, John visited us in San Rafael. And I forgotten exactly what sequence we were working on, but what I do remember was that John stood in the back of the room and listened for a while. And there was one short sequence that I wasn’t mixing quite as well as he would have liked. And so, he walked down in front of the mixing console, stood between me and the screen, and he literally conducted me. Do you remember that, Ben?

Ben Burtt: I sure do. It was the end sequence when the Ewoks sing the celebration song. It wasn't the Boston Pops. He conducted three mixers. But that was fun. I mean, obviously, it's great when you can work together, because it’s not often that the sound team and the composer get to collaborate together.

Speaking of the Ewok celebration song, I wrote all those Ewokese lyrics out. I had a big cue card with verses on it. And that cue card was taken to England very seriously, and I got these tapes when we got the music back. John had the London Symphony choir do the Ewok vocals, in this perfect, classical, style, like it was Handel’s Messiah. I just couldn’t stop laughing when I listened to it, because it was so precise and so perfect.

StarWars.com: Randy, it was a busy year for you at the 1984 Oscars. Alongside Ben, you were nominated for Jedi for Best Sound, but you also were nominated for two other movies (Never Cry Wolf and The Right Stuff), winning for The Right Stuff.

This was still very early in your career as a sound designer, is there anything you picked up during those early years that you still find yourself implementing?

Randy Thom: I think, inevitably, the work that you do early in your career shapes what you do thereafter. The first movie I worked on was Apocalypse Now and that was my film school.

I was on it for about a year and a half and I really didn't know anything about movie sound when I was first hired. I had done a lot of sound work, but not on film. Ben and I met when I was working on Apocalypse, and he was working on More American Graffiti, which also had a Vietnam War sequence in it. The Apocalypse Now sound effects people and the More American Graffiti sound effects people mounted a joint expedition to go out and record guns and grenades that we could share. It was the first time I got to spend any time with Ben.

When the movie was over, Ben had asked me if I could do something similar on Empire, and I obviously jumped at the chance to do that. Working on Jedi, and then doing the production sound for Never Cry Wolf and then some sound design and mixing for The Right Stuff…all those experiences stuck with me and have had a really big influence on my approach to the work.

On Jedi, I felt guilty even being nominated for an Oscar, because of the degree to which I was standing on Ben's shoulders, who had established the sound for the Star Wars series. But I tried to help Ben realize his vision as much as I could. I would say I had more to do with the success of the sound in The Right Stuff than I did on Jedi. And so, in that sense, it's more appropriate that I got an Oscar for The Right Stuff.

Ben Burtt: That was the biggest year for Northern California in Oscars history. [Laughs.] You know, I took my mother to those Oscars. But we lost to The Right Stuff, which was deserving for sure. It was unique and new, with creativity going down the road of jet aircrafts and rockets.

Since Jedi was “just” Star Wars, we'd seemingly already done it. There was now the expectation that a Star Wars movie would have this elaborate fabric of creatures and vehicles and weapons and ambiences.

Randy Thom: It was an amazing time.

Ben Burtt: Yeah, it was.