Just about everyone reading this knows how innovative Lucasfilm has been since its founding in 1971. And much of that innovation was spurred by George Lucas’ desire to do and show things onscreen -- specifically in his Star Wars movies -- that had never been done before. In fact, he’s long been one of the leaders in cinema’s digital revolution.

But that’s not what I had in mind here. I want to talk about the stuff, the merchandise. Has that same sense of innovation carried through to at least some of the hundreds of thousands of items that have been produced worldwide over more than three decades?

Of course, in the toy businesses innovation means something a lot different than devising ways to film spaceship battles or digital picture and sound editing systems. There are problems of size, pricing, and scale, for example. Trying to take the latest cutting-edge technology developed for military or industrial use and making it “toyetic,” could be hazardous to a company’s health. Adapting proven technology through clever adaptation and design, however, is another matter.

Take, for example, the item that first put Star Wars toys on the map -- and has kept it there all these years: action figures. Kenner wasn’t the first to come up with the overall concept or even the name. Those hard green plastic “army men” from the late 1940s and the 1950s were about the same size, although they didn’t have moving parts. Hasbro coined the phrase “action figure” in 1964 for its line of 12-inch G.I. Joe “boys’ dolls.” But it was Kenner that hit on the right combination of movement and size when it launched its line of Star Wars action figures and vehicles that could fit them. As technology has advanced, so has the design and playability of the figures.

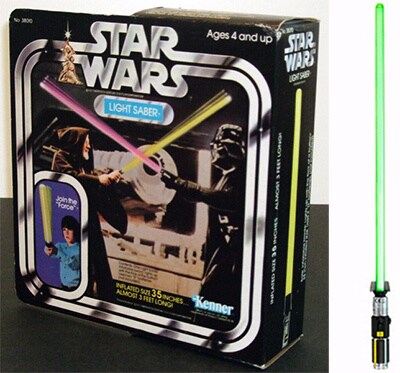

Then there are lightsabers. The first Kenner offering in 1978 consisted of a plastic handle with an inflatable vinyl tube for the blade. Meanwhile, counterfeit light-up sabers were available everywhere. Fast forward a few decades and now we’ve got lightsabers that have ascending and descending lights in the blades and movie-proper sound effects. We still don’t have any that look and work like those in the films -- but science hasn’t been able to devise any like those either.

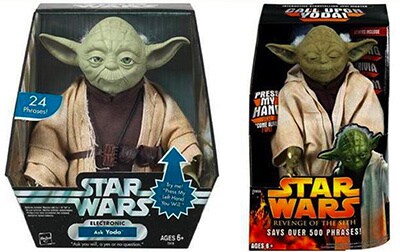

The reemergence last year of Furby as a hot toy (it was first introduced in 1998) brings to mind a number of Yoda toys that have used similar animatronic technology. An eight-inch tall “Ask Yoda” version that underwent several changes gave Yoda-like answers to yes or no questions by pressing his left palm. He gets a little snarky if you don’t keep asking questions. After about a minute of inactivity, he reminds you he’s waiting: “Clearing your mind are you, or another question wish you to ask?” An updated twelve-inch tall “Call Upon Yoda” in 2005 added a 500-phrase vocabulary, story-telling, and trivia questions, and a moving mouth, upper eyelids, and ears.

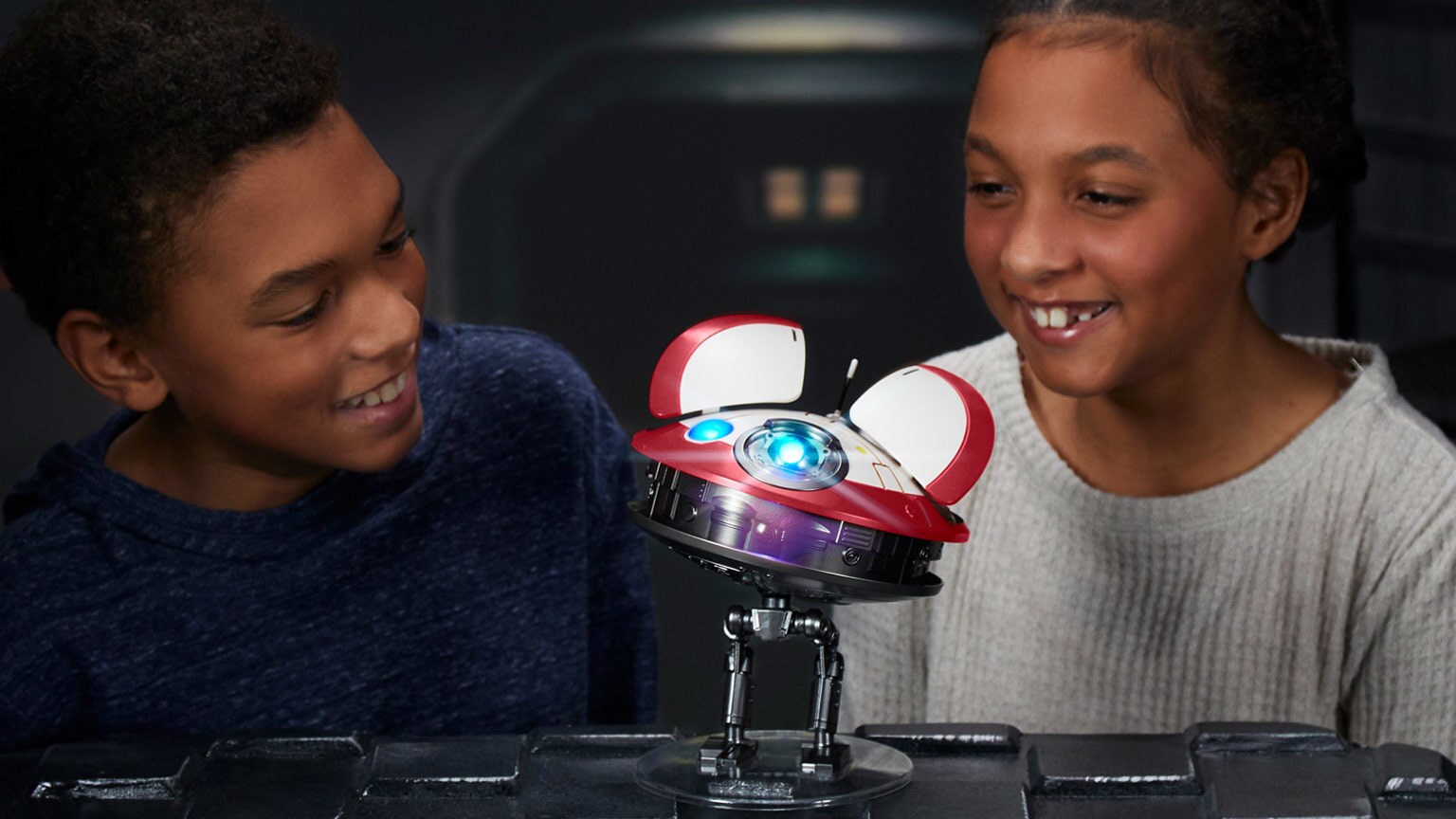

And while there isn’t yet an R2-D2 that can do everything we’ve seen in the movies, Hasbro has been producing a voice-activated Artoo that can move and even do a little dance after you’ve trained it. In 2008 Nikko Home Electronics introduced a very sophisticated, $3,000 R2-D2 video projector just under HD quality that can project a clear 80-inch diagonal image on a wall or even a ceiling with its ability to change its projecting angle up to 65 degrees. It has all sorts of ports and connectors and is operated by a spiffy Millennium Falcon remote control.

Years ago, the top executives of the company that developed Furby (Tiger Electronics, later acquired by Hasbro), once asked me what “real world” toys inspired by the movies I thought Star Wars fans and collectors would like. My wish list included a hologram-projecting R2-D2, a Luke Skywalker training remote, a holographic chess game, and some way to harness the Force so you could use your mind to, say, lift objects just by concentrating.

While I’m still waiting for most of those things, Uncle Milton Industries came up with something three years ago that’s very close to that last item: the Force Trainer. Using technology developed for the medical field, a wireless headset can transmit part of your brainwave patterns (deep concentration is what counts here) to a clear tower. Inside, your transmissions control a small fan that raises and lowers a lightweight ball according to the goal of that particular round of play. It really works, so I still have high hopes that someday those hologram toys will make it to market.

Steve Sansweet is chief executive of Rancho Obi-Wan, a non-profit museum that houses the world’s largest private collection of Star Wars memorabilia. To find out about joining or taking a guided tour, visit www.ranchoobiwan.org. Follow on Twitter @RanchoObiWan and https://www.facebook.com/RanchoObiWan.