Kicking off the highly-anticipated prequel trilogy, Star Wars: The Phantom Menace arrived May 19, 1999. To celebrate its 25th anniversary, StarWars.com presents “Phantom at 25,” a special series of interviews, editorials, and more.

By 1999, sound artist Gary Rydstrom had worked at Skywalker Sound for 16 years. He’d won seven Academy Awards for his work on Terminator 2: Judgment Day (1991), Jurassic Park (1993), Titanic (1997), and Saving Private Ryan (1999). He was on the cutting edge of Lucasfilm’s pioneering work in digital sound technology. But he still hadn’t worked on a Star Wars movie.

“I will point out that I worked on Spaceballs [1987], so that kind of counts,” Rydstrom notes with a laugh. He’d joined the company in 1983, only months after the completion of Star Wars: Return of the Jedi. His work on the Mel Brooks parody Spaceballs and the theme park attraction Star Tours would be as close as he’d get before Star Wars: The Phantom Menace (1999) came along. “That was the first real honest-to-God Star Wars film that I got to work on.”

Rydstrom joined The Phantom Menace crew during post-production as a re-recording mixer, which he describes as “a funny term. It’s called re-recording because we’re putting sounds that have already been recorded into the mixing board. Whether it’s music, dialogue, or sound effects, it’s been recorded somewhere else, prepared for us, and we’re taking all of this stuff onto the mixing stage and recording it again to make it sound like the finished movie.”

The mixing tasks on Phantom Menace were split between three crew members. “I mixed the sound effects,” Rydstrom says, “including lightsabers, explosions, R2-D2, lasers, and all that kind of stuff. I set the levels so that one thing is louder than the other or I take things out if it’s not necessary. I can also add panning. If you have a lightsaber fight — and I think Phantom Menace has some of the better ones in all of Star Wars — you’re placing those sounds on the screen so they come from specific speakers around you.”

Tom Johnson, who had been a classmate of Rydstrom’s in the University of Southern California’s cinema program, mixed the film’s dialogue. Shawn Murphy took the music tracks. “Shawn was not only a re-recording mixer,” notes Rydstrom, “but he was also a ‘recording mixer,’ if you want to put it that way, because he actually recorded the score with John Williams and the orchestra. He recorded ‘Duel of the Fates’ and everything else on the scoring stage, so he knew the music inside and out.”

On earlier projects, Rydstrom had often worn multiple hats. He both designed and edited sound effects for projects like Terminator 2 and Jurassic Park, and then took his own tracks to the mixing board. The Phantom Menace was different. Ben Burtt had been the lead Star Wars sound designer since A New Hope in 1977. Rydstrom and his colleagues would be mixing tracks prepared by Burtt and his team of editors.

“Of course, it’s Ben Burtt,” says Rydstrom, “so it was exciting. It’s still pretty exciting now to think about taking my first laser sound, placing it into the mix, and panning it. It was really cool.” It’s poignant to consider that after more than 20 years of Skywalker Sound’s operation (and its earlier incarnation, Sprocket Systems), only a relatively small number of its employees had actually worked on Star Wars. “Phantom Menace was so anticipated, because so many years had gone by,” says Rydstrom. “As opposed to now with lots of movies and TV shows, there was very little Star Wars material. There was this desire for the big screen Star Wars experience.

“What’s interesting to think about in terms of sound and everything else in The Phantom Menace is that it’s a prequel, so the world is different,” Rydstrom continues. “It’s newer and sleeker in parts. Ben’s sounds for Phantom Menace are different in many ways. John Williams also came up with stuff that was radically new. ‘Duel of the Fates’ sounded like nothing in the original three. The movie had a balance between feeling like a real Star Wars movie, but also being different enough that you found it exciting.”

Though he’d worked in proximity to them for years, Rydstrom had never worked directly with George Lucas on a film project, nor with Ben Burtt. He grew fond of Burtt’s excitement as the sound designer sat in to observe mixing sessions. “He just loved the mixing process because that’s where it all comes to life,” says Rydstrom. “We had this mock-up of a podracer, and we’d set it in front of the mixing console, and as we mixed the podrace, Ben or someone else would sit in it. You were closer to the screen, and it felt like you were actually in the scene.”

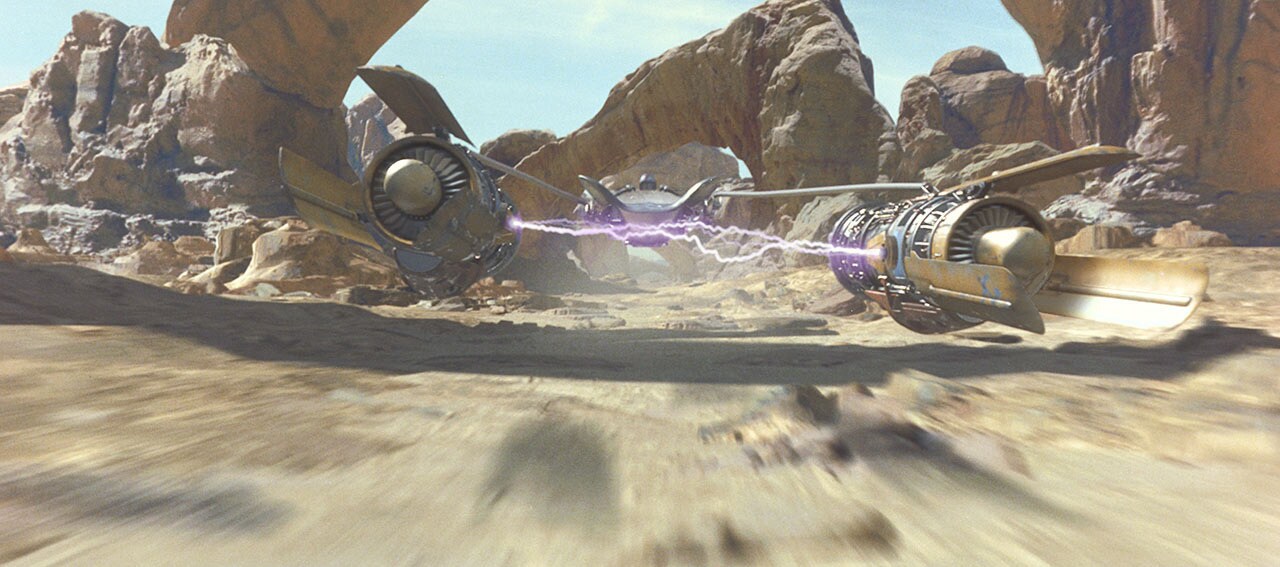

Especially from the standpoint of the soundtrack, the podrace was a marquee sequence in The Phantom Menace. Going back to American Graffiti (1973), speed had been an essential component of Lucasfilm stories, which was, as Rydstrom notes, a reflection of George Lucas’ own passion. “George is a car racer at heart. He wanted to create the impression of what it feels like when you’re right up against these huge engines.”

For Rydstrom himself, the podrace was a sequence akin to Return of the Jedi’s memorable speeder bike chase, where sound takes center stage. “Even though I love John Williams, one of the great things about the speeder bike chase and the podrace is that they hold off on music until the end,” he explains. “It’s just sound effects. You feel like you’re really there in the middle of this insane race.

“We were able to do things with the sounds that would’ve been harder to do if it had been scored traditionally,” Rydstrom continues. “Rhythm is one of the key elements. The engines have a pulse to them. Ben took great care to make the key pod sounds completely different so that you can identify them from cut to cut. You build that dynamic into the scene with these different sounds and by breaking up the really loud moments with quieter moments. George is really good at designing a scene so it’s not just close-up to close-up with constant energy. He pulls back to crowd shots or distant canyon shots, so you can hear the reverb and echo of the podracers.”

An important technical breakthrough for the podrace and The Phantom Menace in general was Dolby Digital Surround EX. As a collaboration between Skywalker Sound, Lucasfilm’s then-subsidiary THX, and Dolby Laboratories (a longtime collaborator on Star Wars productions), the new system introduced a rear channel soundtrack inside the movie theater. Sounds could now travel from behind the audience.

“With the podrace, we had shots where the pods travel directly overhead and then behind the camera,” notes Rydstrom. “It gave us an extra dimension by placing sounds directly behind your head. You hadn’t heard that before. We were anticipating current-day digital systems like Dolby Atmos, where you have a full-range of speakers behind you and even above you.

“There were limitations to what we could do according to how the sound was delivered,” Rydstrom continues. “People at THX had the idea to use — and this is really nerdy — the Dolby optical processor, which would extract four channels of audio from two. You could take two channels of surround and encode a center track into it. Dolby EX could pull out this center rear track and play it back there. At the time, I wanted to do even more, but it was a clever way of using existing standards to extract a new channel out of a system that did not want an extra channel.”

This tool was useful not only for the podrace, but other elements as well, including spaceship flybys, and even the lightsabers, which Rydstrom especially enjoyed. “Doing lightsaber battles is just really fun, with the panning and whooshing and different impacts. You can make it feel really dramatic. You could use the back channel to make it feel like it was really close.” With “Duel of the Fates” in particular, Rydstrom wove an intense yet delicate balance of sound effects in order to complement John Williams’ score.

“A lot of the time, there is a negotiation going on between sound and music,” Rydstrom explains. “Often, I wanted to pull the effects back to let the music lead because it’s so dramatic and beautiful. You want it to read to help tell the story. What I remember about ‘Duel of the Fates’ is that when we first heard it, I thought, ‘Holy crap, that’s good.’ There was no competing with it. I could’ve made the lightsabers loud as heck, and they wouldn’t win. The music is so fast and dense. There’s a rhythm to the lightsabers, but it’s actually much slower than the music. I could do anything rhythmically within it because it was so fast.

“I’ve mixed many films with music by John Williams, and one of the genius things about it is that it’s so wonderful to mix with,” Rydstrom continues. “I don’t think he’s necessarily thinking about what I’m doing, but there is something about it that allows you to bring in those lightsabers, blasters, and explosions, and it’s not going to hurt the score. ‘Duel of the Fates’ was such an impenetrable piece of music that there was nothing I could’ve done to ruin it,” he adds with a laugh.

Intercut with the climactic lightsaber duel were two large battles, one on the grassy plains of Naboo and the other in space above the planet. Mixing the combat sounds for the massive ground battle was an exercise in contrast to Rydstrom’s recent work on Steven Spielberg’s Saving Private Ryan.

“Private Ryan was realistic,” he explains. “Even though we exaggerated things and did our movie tricks to make those battles work, it was trying to stay true to something that really happened. Star Wars battles are fantastical. They’re bigger than life. The effect of Private Ryan can be this chaotic mushiness where you don’t even understand what’s going on. That chaos feels dangerous. Star Wars is articulate. It’s clean. You might not want to hear every machine gun in Private Ryan, but you want to hear every laser in Star Wars. There’s a rhythm between lasers, explosions, and vehicle pass-bys. That’s built in editorially, but it’s my job as a mixer to make that articulate so that you believe it. It's not real in the way that Private Ryan is. It’s a ‘movie real,’ a ‘fantasy real.’ The battle scenes have to have an unreal beauty to them.”

Mixing the soundscape for the serene, underwater locale of Otoh Gunga was another poignant experience. “Not only was I now doing Star Wars battle scenes having just done Saving Private Ryan,” notes Rydstrom, “but I was also doing these underwater scenes having just done Titanic. [laughs] There’s a beauty to the underwater scenes with the Gungans. It’s not an aggressive world. It was calming and peaceful, including the music. Everything was subdued. Jar Jar’s world is pretty beautiful. That was important to the story.”

Early in 1999, visiting journalist Larry Blake wrote in Mix magazine that there was a “palpable buzz” during work on The Phantom Menace, but also a “prevailing calm.” This was in contrast to what was often a frantic and chaotic scene during a movie’s final mix sessions. Rydstrom credits this to George Lucas’ leadership.

“George had built this new facility that we got to fully use,” he explains. “Jedi had been mixed at the older Sprocket Systems facility in industrial San Rafael. Phantom Menace was the first Star Wars movie mixed at Skywalker Ranch, which George built as a place for relaxation and focus on the work. You don’t go crazy being distracted by everything else. I think he meant it as a joke, but he’d sometimes tell us, ‘It’s just a B-movie.’ He was saying, just calm down and enjoy making it. He was the boss. He owned the facility. He owned the movie. He could take as much time as he wanted, and we took advantage of that. The film broke a lot of new ground both visually and in sound. It was part of the first generation in new digital approaches, and that took time.”

Looking back after 25 years, Rydstrom calls the experience a dream. “If you think about it, the stakes were huge. People had been waiting for years. The movie itself had to deal with people’s expectations, but the making of it was very mature. With time going by, people appreciate it in a different way. There’s a lot of beauty and invention in it. There’s a lot of George in it.”