On May 21, 1980, Star Wars: The Empire Strikes Back made its theatrical debut. To celebrate the classic film’s landmark 40th anniversary, StarWars.com presents “Empire at 40,” a special series of interviews, editorial features, and listicles.

There is a note of hope in George Lucas’s voice as he considers whether or not Darth Vader’s surprising reveal in Star Wars: The Empire Strikes Back could have been kept under wraps in the age of the internet.

“I think it might have!” he says. “Because the thing about it is I didn’t tell anybody -- anybody -- about it. And it wasn’t in any of the scripts. It wasn’t even in the story treatments. I kept that aspect of it secret and I was the only one that knew about it. And it really wasn’t until the day we shot that we told Mark [Hamill] so he could react appropriately.”

As Hamill tells it, the actor who played Luke Skywalker was only the third person to carry the secret, after director Irvin Kershner pulled him aside and said: “’I know it. George knows it. And when I tell you, you’ll know it.,’” Hamill recalls. “’But that means, that’s only three people. So if it leaks, we’ll know it’s you.’”

Weeks later, as Lucas sat outside a recording booth with James Earl Jones reciting the line, “No, I am your father,” the circle widened to include sound designer Ben Burtt and the sound mixers. “The mixers, those guys were all dedicated to being quiet. …They weren’t going to tell anybody,” Lucas says confidently. “But there were very, very few people who knew about it until it was shown for the first time….By the end, with the actors, about 12 people knew what that line was.” Then Lucas reconsiders his initial optimism. Even with just a dozen people, it would be hard to keep such a thing contained in today’s world, he says. “I think, in this era now with the internet the way it is, it’s very hard to have surprises in a movie. And I don’t think you could do it today.”

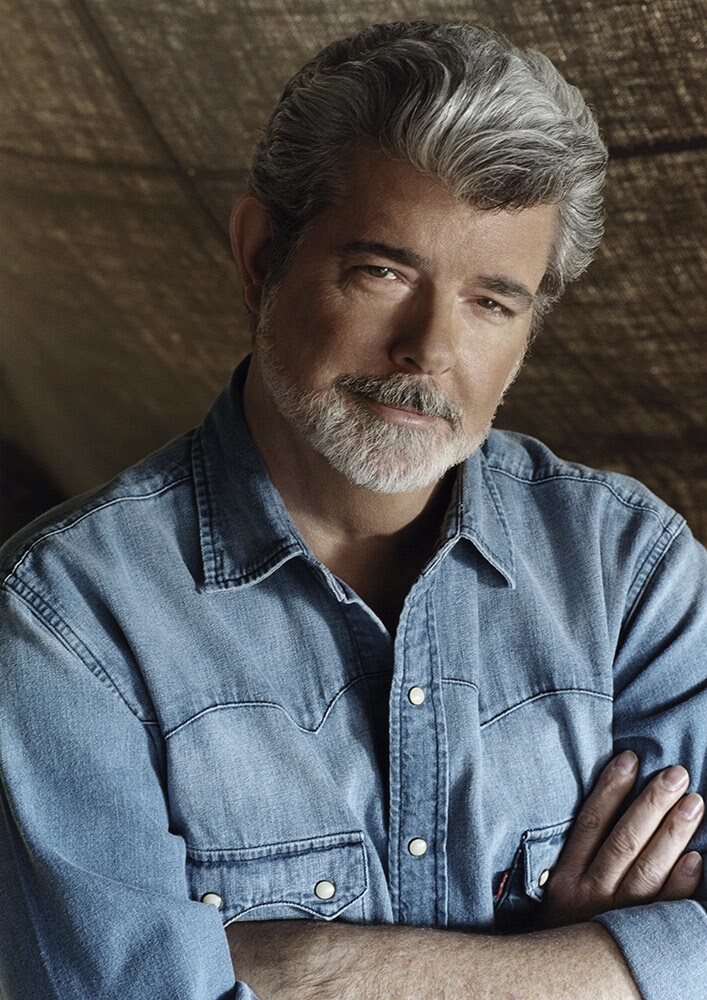

To celebrate the 40th anniversary of The Empire Strikes Back, which made its debut on May 21, 1980, Lucas recently sat down for an exclusive interview with StarWars.com to reflect on the financial and creative gamble that he made all those years ago to bring the second part of his original trilogy to the screen.

“Something my father told me never to do”

In the early 1970s, Lucas was a rebel in the film industry; he moved to Northern California in 1969 and made two low-budget films, THX 1138 and American Graffiti. To ensure he would get the chance to make the follow-ups to the breakout sensation of Star Wars on his own terms, he took on the burden of financing the production himself. At the same time, he was building a legacy in the form of his company, Lucasfilm in Marin County, and making a permanent home just north of San Francisco for the special effects team at Industrial Light & Magic.

Part of his decision to approach The Empire Strikes Back in this way stemmed from his experience working with a big studio, 20th Century Fox, on the first film in the saga. “The studio on A New Hope, they just cut us off,” he says. “There was a lot of stuff that we didn’t do that I wanted to do. But we just didn’t get to finish the film….We were going a week over or two weeks over and they said, ‘Well, we’re just going to cut you off.’” At the time, the movie was still missing its opening scene. “I said, ‘Well, I haven’t shot the beginning of the movie.’ You know, where Darth Vader comes in and there’s that battle and Princess Leia has a conversation with him. None of that had been shot. And they said, ‘Well, we don’t care. Try to make the movie without it.’” Ultimately, Lucas and the crew worked long hours on A New Hope to capture what they could in the final push to their deadline.

As he sat down to plan the production for Empire, Lucas knew he would need more creative control than he’d been granted previously. “I had taken precautions earlier on to control the sequels so that I could continue to make the movies,” Lucas says. “I took control of the movie so I could make all three of them because I knew, unless you have a really big hit with a movie it’s impossible to really get another one made. Especially in those days. And I had no idea [the original Star Wars] would be a hit movie so I was working from the assumption that it wasn’t going to make money and that it was going to be really hard to finish all three of them. And I was dedicated to do that.”

That also meant financing it, no small feat even after the success of Star Wars. “Well, to be very honest, the most challenging aspect was paying for it,” he says now. “In order to be able to take control of the movie, I had to pay for it myself. And in order to do that, I did something my father told me never to do, which was to borrow money. But there wasn’t much I could do because I only had maybe half of the money to make the movie so I had to borrow the other half, which put a lot of pressure on me.”

Just getting the script ready for shooting was its own ordeal. “I was learning…I don’t like writing,” Lucas says. “In this case, Leigh Brackett died literally the day she turned the first draft of the script in and it wasn’t really much like I had expected or wanted and so I was stuck. I had been working with [screenwriter] Larry Kasdan on Raiders [of the Lost Ark] but he wasn’t finished yet.” Lucas asked Kasdan if he would work on a third draft of Empire with Lucas tackling major plot points in the second draft. “And he said, ‘How do you know I’m a good writer?’” Lucas recalls. “And I said, ‘Well, when you turn in the script, if it’s no good then the deal’s off.” Lucas worked on the second draft “and then while I was reading Raiders, he was writing Empire.”

Delays from the start

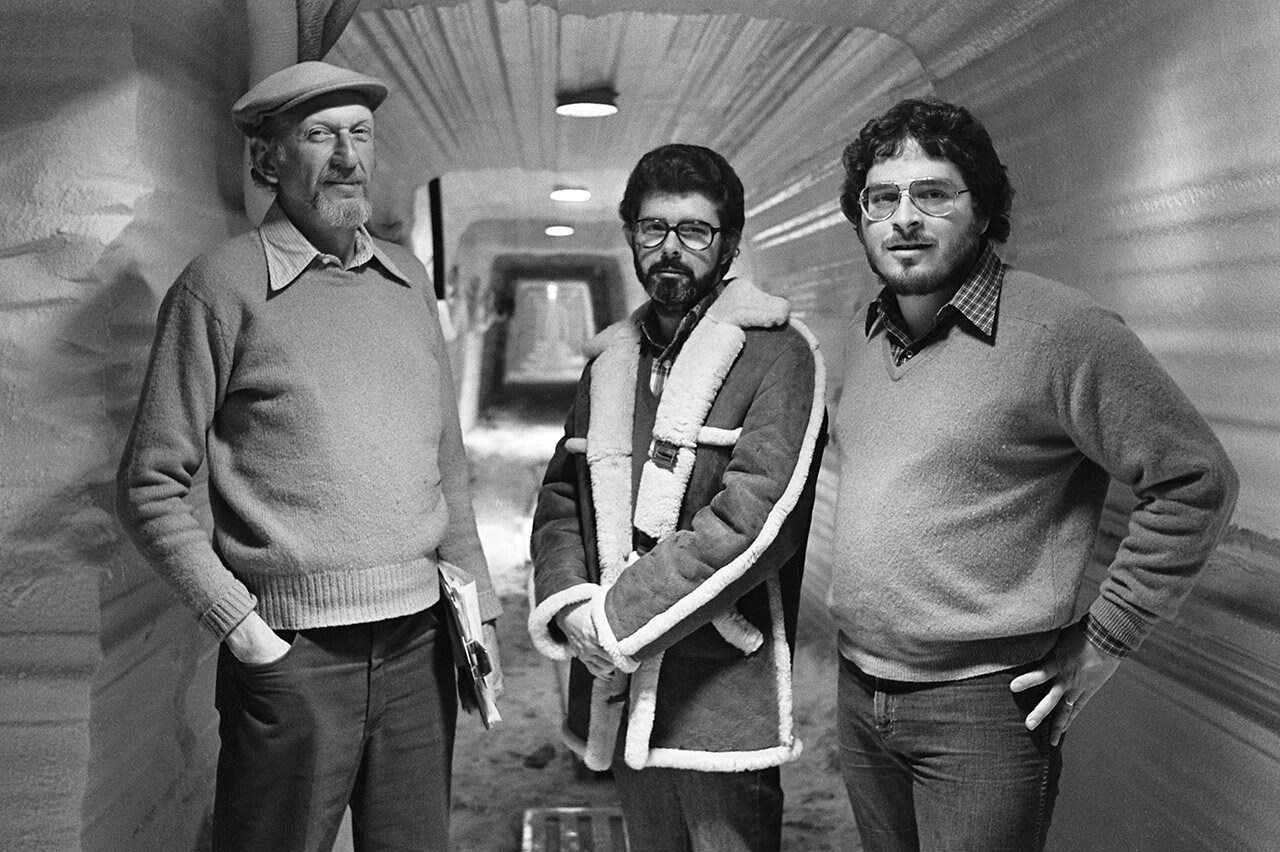

To direct, Lucas called on his friend Irvin Kershner. “I was moving Industrial Light & Magic up here to San Francisco, where it was supposed to be in the first place. And I was working on making Lucasfilm, which existed, but…we didn’t really have the merchandising part,” Lucas says. “So I knew I had a lot to do and it would be very hard because, when I direct, I really am there 24/7. And I thought I would need a little extra time to sort out Lucasfilm. And so that’s why I felt I needed to hire a director… I couldn’t run a studio, build ILM, and direct a movie at the same time.”

Lucas and Kershner had met while Lucas was studying at the University of Southern California. “I knew Kershner from school. He was a friend and I figured he’d be good for it because he was a really great director. And then once we started the movie, I thought I’d be able to spend some time back here in San Francisco trying to get everything sorted out with the company, but as it turned out when they went over to Finse to shoot the Battle of Hoth, they came back and they were weeks late and overbudget.”

That delay at the start of the production would set the tone for a veritable avalanche of pushed deadlines and rescheduling that allowed the film to be completed closer to Lucas’s vision than the first Star Wars, but at a higher cost. “They were supposed to shoot [the Hoth scenes in Finse] in two weeks and they shot it in months, so we were already way behind schedule. And so it created a lot of havoc. We were projected to go way over budget and I’d already borrowed all the money that I could. I went to the bank and they said ‘No, we’re not going to extend the loan.’ Which meant, basically, I’d lose the movie.” A second bank agreed to give Lucas another loan, compounding the financial pressures. “And then I realized that the movie was just going to keep going over budget and over budget and over budget unless I went over there and watched over it. So I spent the rest of the time in England working with Kersh and trying to get the movie done at a reasonable budget that we could afford.”

In stark contrast to his experience on the first film in the saga, which had chafed, as the producer this time, Lucas tried to be more compassionate with the crew on Empire. “Since I was financing this one, I wasn’t quite that Draconian about how we were going to finish,” Lucas says. “I had to accept the fact that we were going way over budget, way over schedule.”

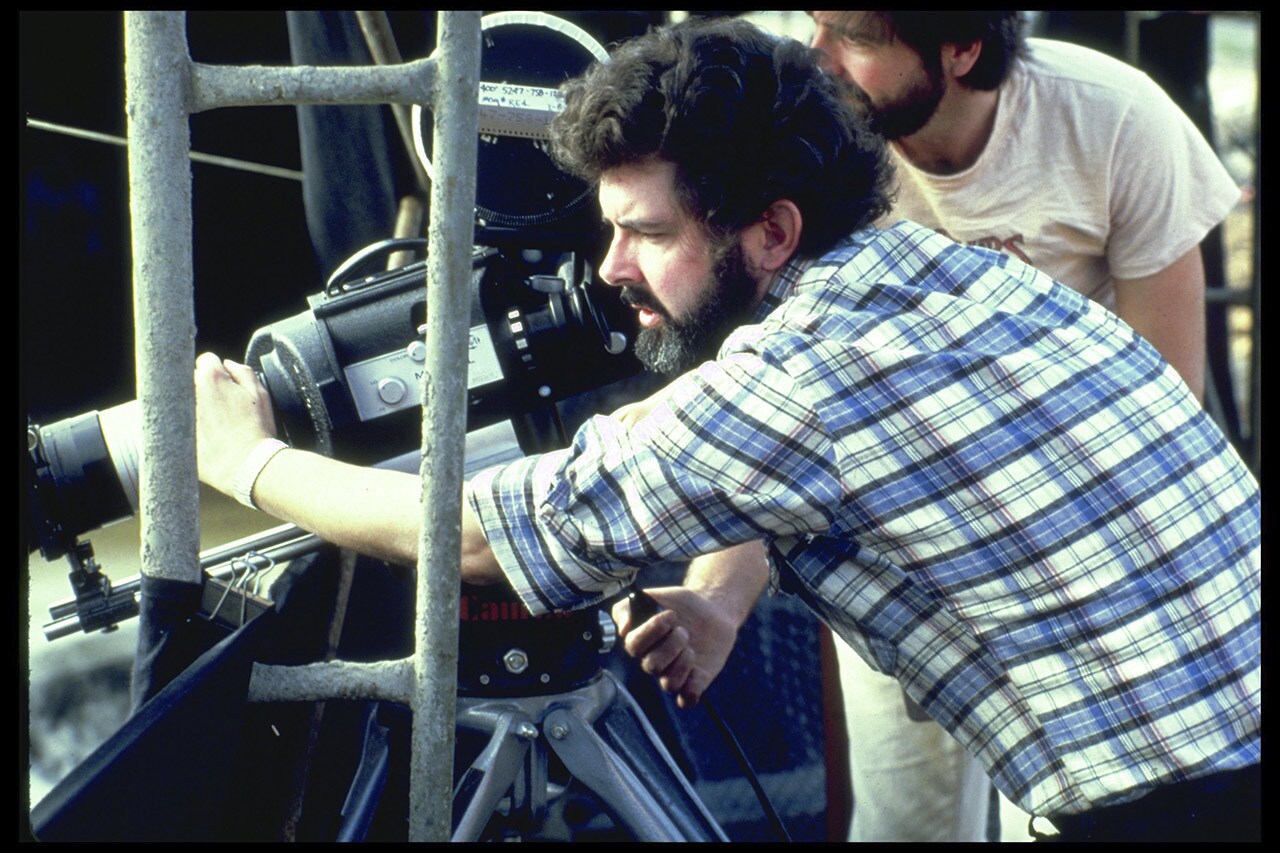

Once again, Lucas’s vision called for pushing the boundaries of filmmaking special effects. “Every movie, especially these kinds of movies, right from the beginning the visual effects are always extremely challenging and in every movie I sort of pushed the goal line down a bit,” Lucas says. “And everybody panicked and said ‘We can’t do this.’” But Lucas could always keep up morale with his earnest belief in the ingenuity of his crew. “I’d have to go in and give them a pep talk that we could actually move on and do something that had never been done before. So that was always a challenge, just making sure the crew and everybody, especially the ILMers, had the enthusiasm to keep going….You have to be a cheerleader and you just have to convince them that this will work, that it’ll be great.”

That hadn’t always been the case. “On the first one, the production crew on the set, except for the art department, just thought it was a joke. And they were not that interested in the movie or helping or doing anything except getting their paycheck. ILMers were always enthusiastic because they were very young. And young people are enthusiastic,” Lucas says with a warm chuckle. “They knew we were doing something that had never been done before and so that excited them and that kept their morale up. And even though we went through some very hard setbacks, I had to go up and be a parent and say, ‘We can do this. We’re not going to give up. We have to keep going.’ You just have to say, even though everything looks like it’s falling apart, trust me, it’s actually not.”

“Kinetic energy”

Fortunately, Lucas and the team at Industrial Light & Magic had learned a tremendous amount working on the first film, with groundbreaking special effects and behind-the-scenes inventiveness like the Dykstraflex, the first motion-control camera system, that made audiences feel as if they were truly hurtling through space inside the cockpit of an X-wing. “In terms of visual effects, you just couldn’t do those things. Nobody had ever done them before and you didn’t have the equipment, you know? It hadn’t been invented yet,” Lucas says looking back on it. “So on A New Hope, we invented a lot of the technology. And the guys that were working at ILM were learning how to make that kind of a movie.

“We carried that kinetic energy from Episode IV to Episode V, where you could pan with things, things would move fast, and you get a more naturalistic feel to the movie. And, you know, we did kind of the same thing we did with Episode IV. We did little animations of the battle sequence, little stick-figure animations.” The low-tech solution “was some of the very early forms of pre-viz,” Lucas says, and it allowed for a more cost-effective production. “The only way we could do the movie and get it done for the price was to use as few frames as possible on each visual effect shot, which meant if I had a shot that ran 32 frames, they would give me 36 frames, a couple clean frames on either side.” Then they matched the finished special effects shots to make sure they were cut the same length as the animations. “Each frame would cost like $20,000, so you just couldn’t make mistakes,” Lucas says. “You had to really get it down to the actual frame. And nobody had ever tried to do that. And that’s one of the ways we were able to make the film less expensive.”

The triumph of Master Yoda

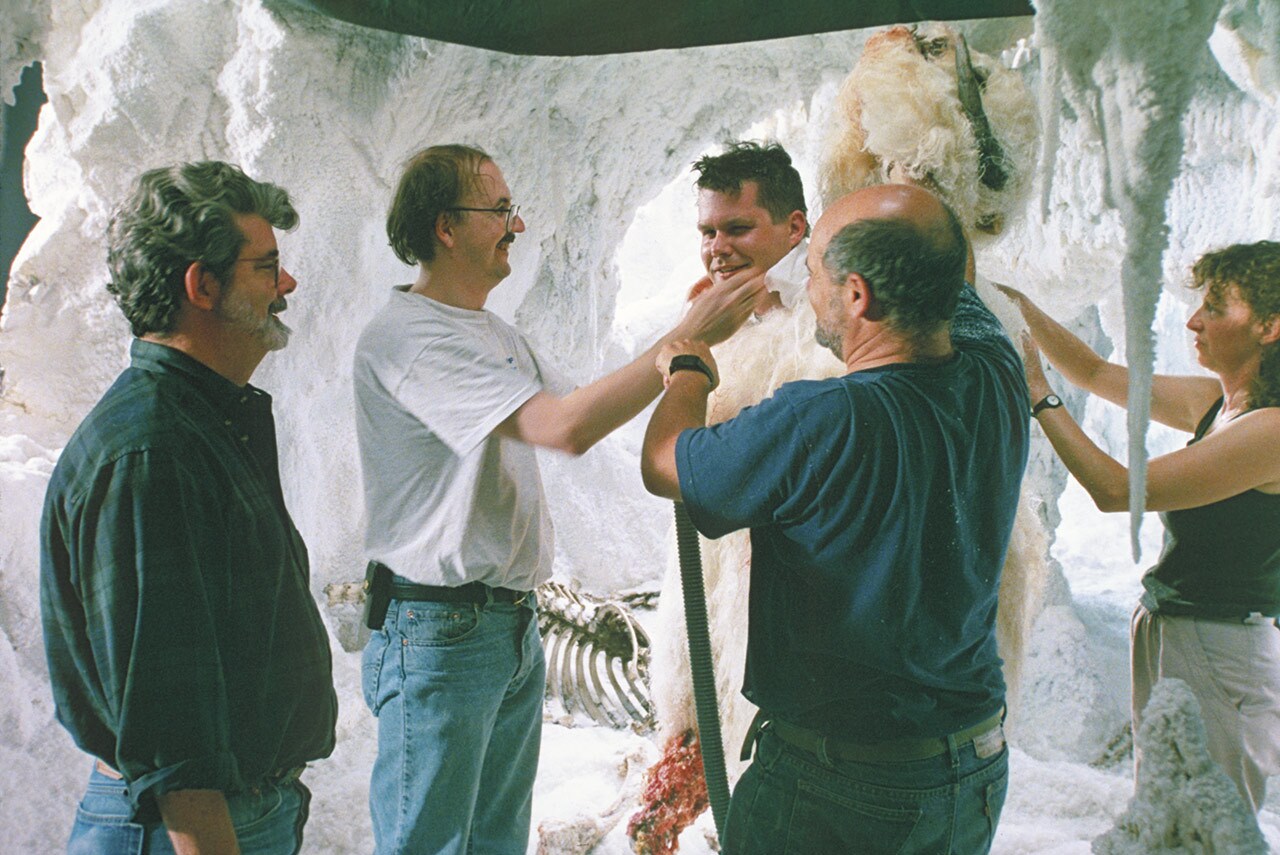

Never satisfied with simply regurgitating the lessons from his previous work, Lucas continued to push the boundaries of filmmaking with blue-screen special effects in the Battle of Hoth and the wise and diminutive Jedi Master Yoda.

More than a puppet, the Yoda prop was a complex and cutting-edge conglomeration of technology and articulation that often broke down on set and needed to be sent back to creator Stuart Freeborn’s shop for repairs. In the literal trenches below the camera’s eyeline, Frank Oz and his team worked to create Yoda’s unforgettable performance.

Lucas knew this, too, was a gamble -- requiring the gravitas of the film’s message on the fabric and nature of the Force to rest on the small shoulders of this strange new alien. Kershner treated Yoda like an actor on set, sometimes talking to the prop instead of addressing Oz down below. But it would be weeks before Lucas could be sure that Yoda, as we know him, was a success.

“I didn’t really understand it until the first day of shooting, and seeing the dailies and seeing it in action and under the right lighting conditions,” Lucas admits. Like many aspects of the film, the team working to create the complex Yoda puppet was putting the finishing touches on it down to the wire. “A lot of those things, like Yoda, got finished like an hour before we shot it. Everything was always on the run. So I finally got to see the whole thing finished, put together, lit properly, and that’s when I knew it was going to work,” Lucas says. “Before that I had to rely on Frank Oz. Frank had performed great in rehearsals and Stuart Freeborn was working very diligently on trying to get the puppet to work, but it didn’t convince me until I saw the actual movie.”

Even then, it was the audience that really had to be convinced. “If it hadn’t worked, obviously the movie would have been terrible,” Lucas says pragmatically. “It would have never worked….And you don’t really know until you actually show it to an audience and they don’t get up and storm out and say ‘This is stupid.’”

“They were just characters”

Of course, Yoda was a success and, like its predecessor, The Empire Strikes Back became a box office hit and an enduring classic. Years later, when it was time to give the trilogy the Special Edition treatment, Empire stood as the film that would have the least amount of changes, although Lucas would work to rectify the wampa's scene and alter Palpatine. “We had a second unit trying to shoot the wampa monster and they took months," Lucas recalls from the original production. "I mean, it was a one minute, two minute scene. It took lots and lots of footage and we didn’t really get it. So we had to reshoot that when we came back to San Francisco.”

Characters like Boba Fett would go on to capture imaginations and make way for new storytelling in Star Wars: The Clone Wars and The Mandalorian years later, in the ever-expanding galaxy that Lucas had built.

Looking back on it now, “It wasn’t the most fun movie to make, but it was definitely a rewarding film,” Lucas says. “It turned out well. I learned some things. I thought I could let somebody else direct the movie and still run a company and I realized that wasn’t gonna be possible. So I put the company aside and stayed there with Kershner helping him.”

Forty years later, the new characters in The Empire Strikes Back, from the wise Master Yoda to the smooth-talking Lando Calrissian, and the story that leaves heroes like Luke Skywalker, Princess Leia Organa, and Han Solo completely down on their luck and defeated by Darth Vader and the Empire, still resonates with fans and viewers. But even now, it’s hard for Lucas to pinpoint exactly what it is about Star Wars that sticks with people for so long. “Well I don’t know,” Lucas says. “Even though it’s an homage to ‘40s movies and a space opera -- where the characters are pretty cardboard -- I worked very hard to create the characters that would be iconic in their own way, and still be true to the classic adventure cinema.”

His characters were relatable because they had fears and doubts. They were driven by moral conundrums that weren’t just black-and-white dilemmas. And each character had complexities that gave birth to their actions, making the audience root for them and worry for them as if they were people they knew in real life. “Their motives were driven based on psychological motifs that had been around for thousands of years in mythology,” Lucas says, which helped to make their stories timeless.

“I mean it’s also from Episode IV, which is the first time you treated aliens as humans, as if there was nothing special about them, they just look funny,” he adds. “They were unique but they weren’t monsters. They weren’t crazy aliens. They were just characters. And I don’t think anybody had seen that before and I think they liked it.”