On May 21, 1980, Star Wars: The Empire Strikes Back made its theatrical debut. To celebrate the classic film’s landmark 40th anniversary, StarWars.com presents “Empire at 40,” a special series of interviews, editorial features, and listicles.

Inside Ben Burtt’s home office, he’s flipping through a notebook from his time working on Star Wars: The Empire Strikes Back in search of the name of the farm where he recorded the sea otter behind the bleating vocals of Hoth’s tauntauns and a bathtub full of raccoons for Dagobah’s unseen wildlife. Among the copious notes and audio tapes from his more than four-decade career is a detailed record of the nine months Burtt, the sound designer on the film, and his team spent on road trips across the United States where they recorded everything from a squeaky dumpster lid in Burtt’s yard to a lion feasting on an animal skull. More than a quest to create the soundscape to convey the otherworldly ambiance of Dagobah and so many other locations, vehicles, creatures, and sounds in the Star Wars sequel, it was also the chance to capture more than 1,000 individual audio elements to create the basis for what would become Lucasfilm and Skywalker Sound’s audio effects library.

As for that tauntaun? “It was an Asian Sea Otter that was recorded at a game farm to the south of [San Francisco],” Burtt says from behind his notebook. “The sea otter had a very high-pitched squawking and the nice thing about it was that it almost sounded like it was talking.” For a moment, Burtt slips into his own rendition of the otter’s chattering, one of many sound effects he intones in his storytelling. “Slowed down, it became a terrific tauntaun.” The name of the animal was Mota, he finds, scrawled next to the date of the recording. “But it doesn’t say the place,” he says. “What kinda notes are these, Ben?!”

The tauntaun

Raised in a family of scientists, Burtt’s approach to sound design in the late 1970s had a decidedly academic undertone. “I was thinking I was going to be a science teacher,” he says. “I was brought up in a family of scientists…notes and notes and lab coats. And I was a physics major in college, so I was just trained to keep a record of what I was doing professionally. I don't think I was thinking I’d be doing interviews 40 years later.”

But more than a scientific log, Burtt’s notes are a window into his creative process, his passionate energy for capturing sounds and preserving the history of sound in filmmaking. “I was always very interested in the history of sound effects in Hollywood in general, everything that led up to my career, and yet I found there was no information saved,” he says. “There’s very little behind-the-scenes material going back into the 1940s or 1930s about sound effects, and it’s extremely rare that any information comes to the surface because no one at the time left a record. They obviously didn’t do behind-the-scenes documentaries or interviews. Sound was not important enough to get documented, and the studios liked to keep their process a trade secret.”

And yet, when George Lucas first brought moviegoers along on a journey into a galaxy far, far away, he knew an authentic audio track, created from real-world sounds artistically manipulated and layered, could help define and create all-new worlds and make them feel entirely lived in and believable. To celebrate the 40th anniversary of The Empire Strikes Back this year, Burtt digs into his personal archives to share some of his favorite stories behind the sounds that defined the film.

“An investment for the future”

From the outset, Lucas and everyone else returning for the second film felt the tremendous onus of expectation surrounding the next chapter in what had become a worldwide phenomenon. “The first film, we were all innocent and made a film that we wanted to see ourselves,” Burtt says. “And even though there was lots of stress to get it done, we were young and we were vigorous and what did we have to lose? There was no reputation to uphold, and no one foresaw that there was going to be a reputation.” But as pre-production began on Empire, “now we were all defined as award-winning geniuses….It was kind of a reckoning as to how we are going to survive it, because it was so much high expectation to do it again. The lesson you learn is you can't really do the first Star Wars movie again.”

For his part, Lucas envisioned an even grander film with planet-hopping escapades that would take viewers on an odyssey from the barren icy wastelands of Hoth, complete with native creatures and snowspeeder-stomping AT-ATs, to the otherworldly beauty of Bespin, a city that truly belongs among the clouds but would also contain the multitudes of a bustling metropolis, and the sizzling sounds of an epic lightsaber duel and a carbon freezing chamber. And in between, Yoda’s humble but swampy home of Dagobah. While the industrious minds of Industrial Light & Magic worked on never-before-seen visual effects, Burtt and his team were busy considering every new element that would need to be heard. From the script, they began a list. “I would say there were about one thousand different things that needed to be addressed in the movie in terms of projects for sound effects creation. I went back a few years ago and I counted ‘em up,” Burtt says. “The organic nature of the sound is the defining basis for everything done in Star Wars. That was really George’s direction from the beginning, so we got used to that sort of thing and looked for it.”

Of course, not everything gathered in 1979 and 1980 made it into the film. “I had created sounds for the first Star Wars film, but we didn’t have a basic library of fire, crashes, footsteps, animal sounds, wind, and so on. So, the reason Empire had so many target categories was because we said, ‘We really need a Lucasfilm library of just all kinds of stuff -- doors, weather, water. And so that’s probably why the list was so big, because we needed to have that core library. And that library would go on to be used in Indiana Jones, and the legacy of Skywalker Sound today is that core library which was recorded then,” Burtt says. “So Empire was a big task because I said, ‘We need a library for the studio.’ And [producer] Gary Kurtz was onboard with that idea and made sure we had a budget to travel if we needed to. If we wanted to go to the state of Washington to record a bear, we could do it. If we wanted to go to Oklahoma to record a building demolition, well, we would send somebody or I would go. Lucasfilm looked at this as an investment for the future.”

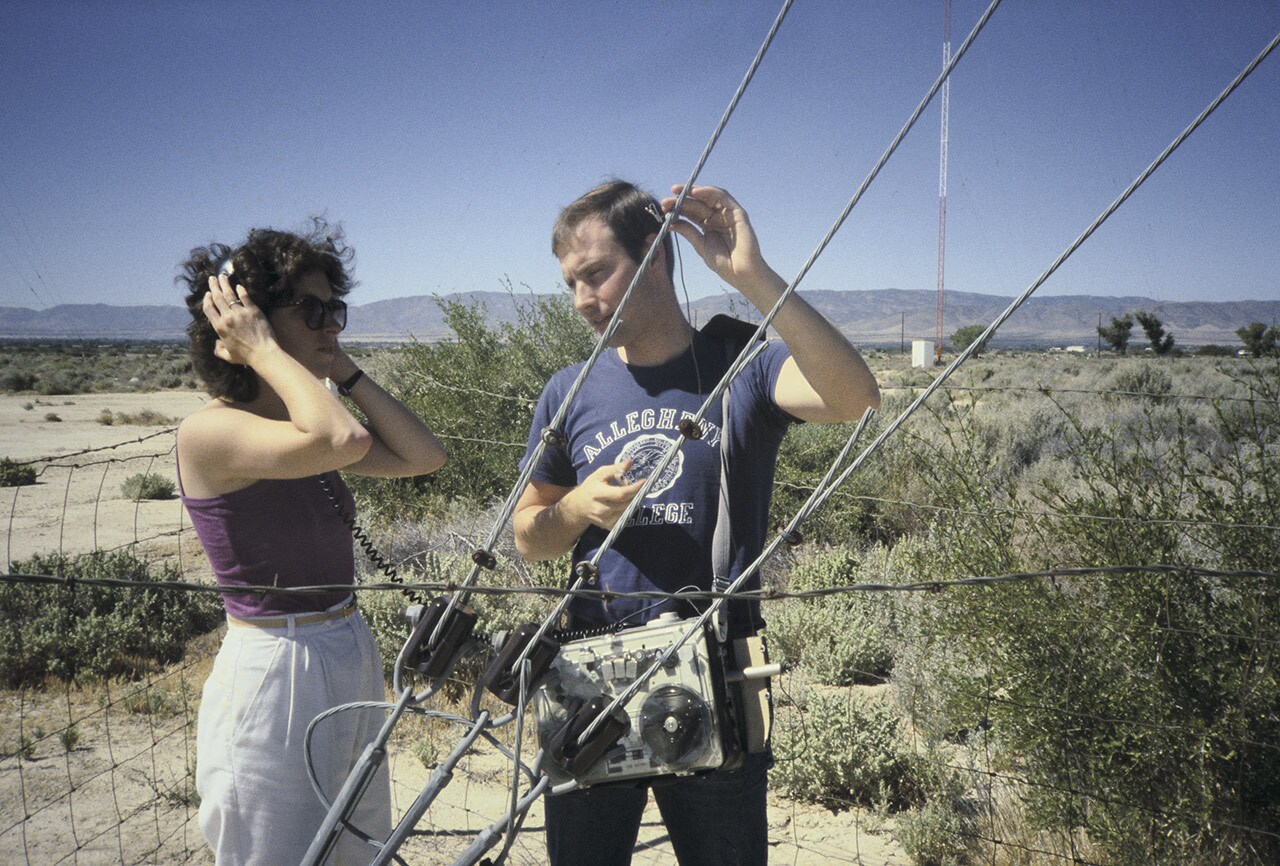

Burtt and his assistant at the time, Gary Summers, began the work, “and later we hired Randy Thom, who’s still at Skywalker and is a legendary sound designer and mixer. He came early on during Empire. I met him at Zoetrope when I was working on Apocalypse Now.” It was Thom who was tasked with capturing the metal sheering machines to create the unmistakable stomping sound of the AT-ATs. “I would say, ‘Randy I need some squeaky metal and some machines for the walkers.’ And so Randy would go out and find things and drop off tapes and I’d go through them. I’d send Randy and Gary out, and sometimes a guy named Howie Hammermen who was our engineer. Anybody who could carry a recorder, I guess,” Burtt says with a laugh. “We gathered all of these sounds, tape after tape after tape, and they’d be on a shelf, and I would come in in the morning and I would pull out what Randy might have recorded and go through it. I’d listen to everything he did and I’d pull out the things that I liked, I'd make a copy of it onto another tape, everything was on tape in those days,” he says, pulling one from a long lineup on a nearby shelf. “Here’s a tape from Empire!”

Burtt reads off the label; it’s marked “Calistoga Soaring Club,” from when his crew captured the sounds of gliders. “And we sent Gary to an aircraft carrier to do jets landing and the mechanics of all the things. It was really a thousand-recordings-project and we went all over the place. I was focusing mostly on animals to convert into the alien creatures in the film, or ambiance on Dagobah. So I was going to game farms where I could record bears and lions and exotic things.”

Animal sounds

To help set the tone for Dagobah, one of the animals on Burtt’s list was a raccoon, a chittering sound that could be slowed down to build up the vast swamp planet thriving beyond the camera’s frame. “We wanted Dagobah to be teeming with off-screen life; life that you basically didn’t see,” he says with a laugh. “It was entirely invisible. It was under the leaves or under the bark or something in the trees.” Among the sounds in the mix were woodpeckers in the Redwood forest, an old-fashioned hand water pump, and birds recorded in the San Francisco Zoo’s aviary. “They had a giant cage that had birds in it and it was very echoey. When you recorded in there and slowed it way down, way down, the little high-pitched chirps became unidentifiable unknown creatures that sparked your imagination.”

But for the most part, zoos, Burtt notes, are just too noisy between the odd noise of sprinklers or the murmuring of humans for capturing isolated audio. The animals themselves already pose enough of a problem. “Animals are noisy and you had to come up with a method of isolating the animal from unwanted noises. Often the animal wouldn't sit still and you’d get skittery footsteps on the dirt ground,” Burtt says. “In the case of the raccoons, they just wouldn’t stop moving.”

At a game farm to the south of San Francisco, Burtt and the owner took a couple of raccoons into the farmhouse. “And then we decided to put them in the bathroom where it was quieter and closed the door. We put them in the tub -- the empty tub -- because then they couldn’t get out. It was slippery and the animals just stopped moving and sat there crying,” Burtt says. “I know, there’s so many crazy animal stories like that because animals, they don't take direction.”

Another day, Burtt went in search of chimpanzees at Marine World Africa USA, to the south of San Francisco. “We couldn’t get the chimps in a quiet spot, but then someone suggested ‘Well, we can do it in Bob's office.’ ‘Cause, you know, Bob was on vacation,” Burtt says laughing. “We put the chimps in there and we sat around with the microphones. The chimps started going wild! They opened the drawers of his desk and threw pencils and papers in the air. They jumped around knocking about furniture and books. Surprisingly, we got great sounds of the chimps, but when I left Bob’s office was trashed, like an earthquake had hit. The chimps were so curious about everything in there!”

Hoth wildlife

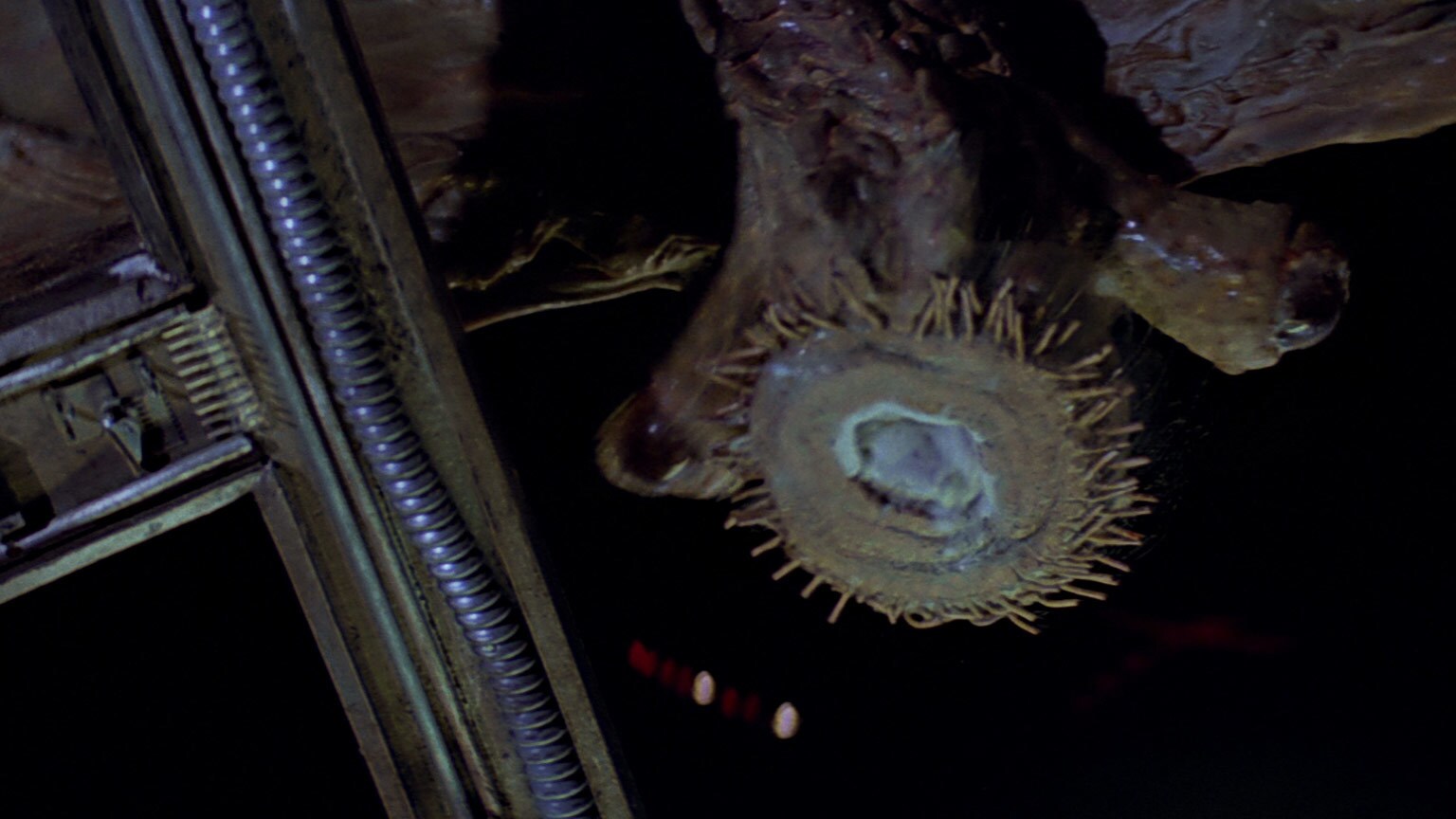

The job also took Burtt to the Olympia Game Farm in Sequim, Washington, where he was able to capture camels, lions, and other exotic mammals to help populate Empire. He went there while working on the Star Wars Holiday Special, specifically hunting for the sounds of bears to round out Chewbacca’s family of Wookiees. Burtt and his team stayed for three days. “It was one of our best recording trips for animals,” he says. “One of our favorite ones was ‘lion eating a cow’s head’,” Burtt says with a chuckle. “It was this long recording of a lion moaning while chewing on this cow’s skull, and boy -- did we get a lot of mileage out of that one!” Listen carefully and you might just hear it for yourself as the wampa settles in for a feast inside its icy lair.

The rancor

“It has slurping, crunchy chewing, and grunting,” Burtt says. To complete the effect of the toothy predator, Burtt added in a decidedly less vicious creature -- an elephant. “There were some good elephant roars that we got at the Oakland Zoo that were used for the wampa when it really yells.” The raw sounds would later be used to give voice to another misunderstood creature considering Luke Skywalker as a snack. “A lot of that stuff was reworked for the rancor,” Burtt says.

The mynock

And of course, who could forget the mynocks? “The mynocks! They were horses backwards,” Burtt says. “You know, when a horse whinnies? When you do it backwards, it’s funny, something as simple as a horse, but you don’t recognize it backwards. It sounds like some kind of shrill horror-creature vocal.”

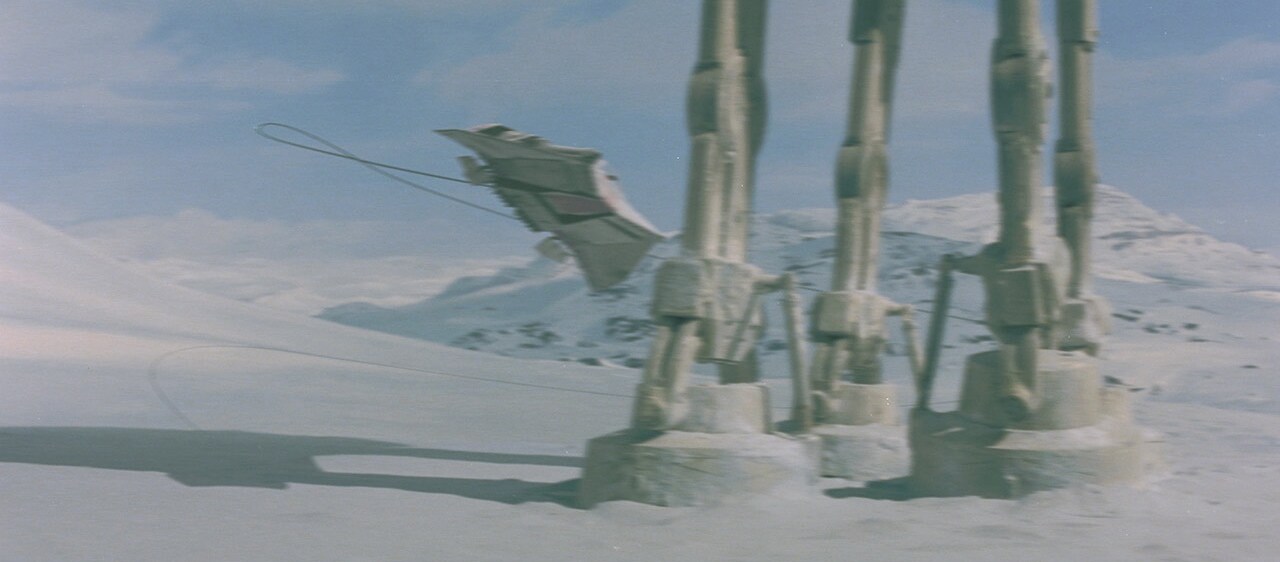

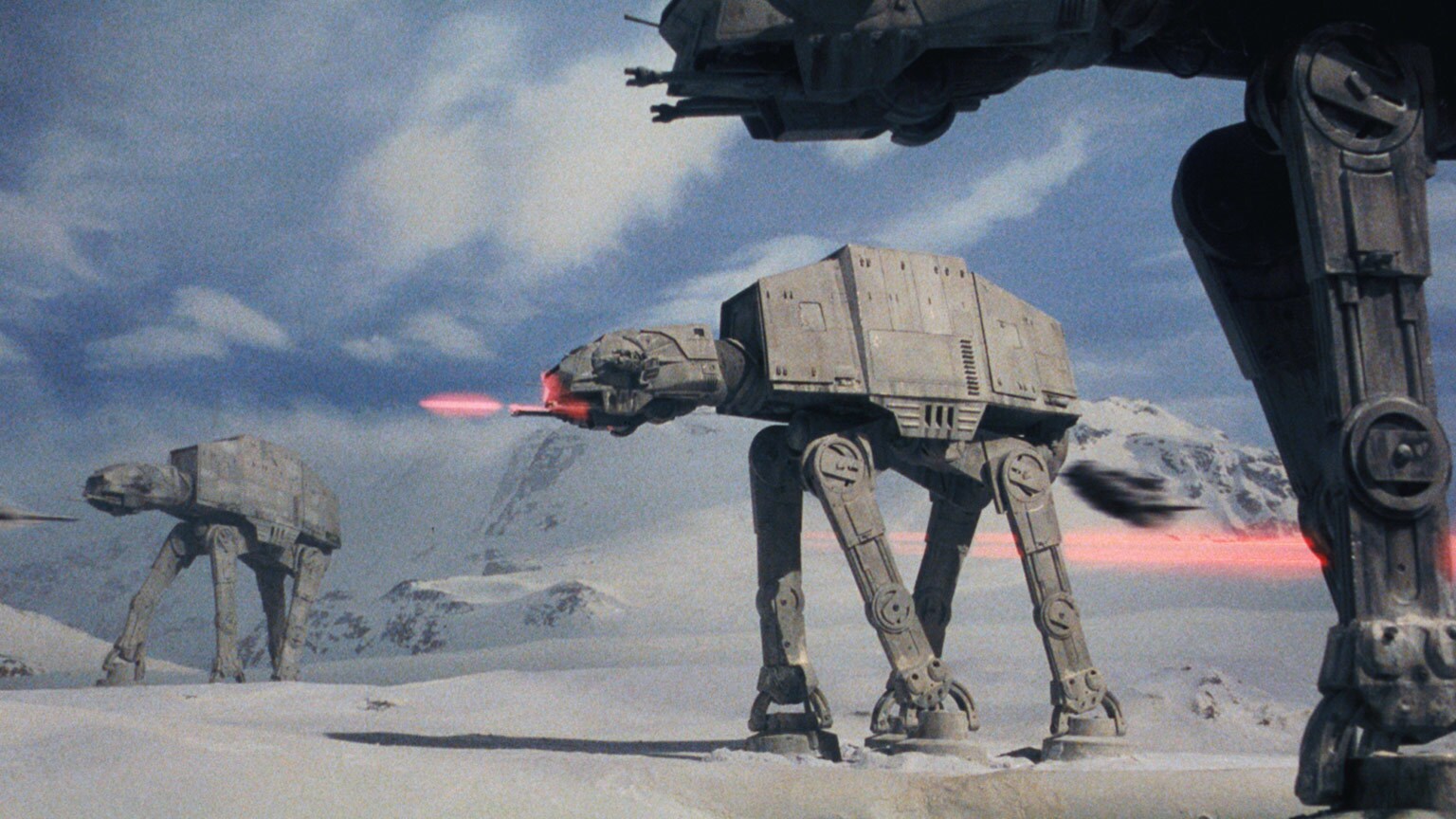

A mechanical beast

When it came to capturing the lumbering steps of the AT-AT walker, Burtt and his crew started ideating from the earliest days of pre-production. “We had seen Ralph McQuarrie’s paintings of them, and there were some sketchy videomatics that ILM did, almost like animated storyboards,” Burtt recalls. “Ink drawings done crudely. It was the best we had for videomatics at the time, action poses that George could cut together and make an animated sense out of the battle.”

Burtt gathered many of the individual sounds that would be mixed together to put the Imperial walkers into motion. “That was a particular focus of mine,” he says. For “the metallic sounds of the squeaking joints,” Burtt didn’t have to go far, famously recording the squeaky lid from a dumpster in front of his home. “It’s the sound I’d hear when I’d throw the trash away,” he says, mimicking the noise of opening the lid.

The AT-AT walking

“There was the stamping of the feet and the rhythmic sound of the engines, and that really came from two different sources. I think Randy [Thom] recorded the elements for both. One were the metal shearing machines.” At a factory on Oakland, California, “it was a place where a sheet of metal comes down a conveyor belt and then it would get stamped, knocked into different shapes, or embossed with a pattern,” he says making a clunking sound for effect. “It was a big stamp. And Randy started recording those, and we sent him back a second time. There was a nice variation of heavy stamping that had some clickety-clacks to it….The other element on the walkers which is running constantly is an oil derrick pumping,” he notes.

To give the towering mechanical beasts a feeling of crushing mass, Burtt captured the exploding sounds of artillery shells. “The actual weight of the foot,” he says, “Fwoomp! Fwoomp! Fwoomp! That was an artillery explosion that was recorded in Oklahoma. I went to a shooting range there where they fired at me from five miles away, and they were actual high explosive shells. It was the real thing. I was with a guy called a spotter -- it was a soldier with a radio -- and he’s telling them whether they’re near the target or not. So there’s a target out, maybe two or three hundred yards out in front of me, and we’re in a trench.

The AT-AT firing

“I put my microphones out there on a long cable, ran it all the way back, and then got down in the trench with this soldier.” Both men were wearing helmets, Burtt notes, but it was still a harrowing experience. “We were hunkering down and they would fire at us from five miles away. You’d hear the shell coming, you’d hear the distant thump of them firing the shot, and then a moment later there was this -- it sounded like a jet plane coming through the sky and that was the artillery shell. It would explode and send shrapnel everywhere, [it would] come pinging and zipping around….The pressure goes up in your ears and you feel the vibration. That whoomp! of the 155-millimeter Howitzers was used for the actual step of the feet. It was this nice, heavy, low-end, thump sound.”

A cacophony of other motors helped round out the sounds of the massive machines raising and lowering their legs. “Motors that operate a tank turret and cannon ,” he adds. “The movements became this mixture of a whole bunch of different elements….Great recordings, by the way.”

The wailing winds

The winds of Hoth

Some natural sounds, like the wailing winds of the frozen tundra near Echo Base, could be captured during location shoots, but still needed to be amplified and remixed. “Although we thought there would be some sounds from Norway, there really wasn't much,” Burtt says of the location shoot. “It was such difficult conditions that they couldn’t really get any usable sound. They barely got the shooting done! The only audio that came back with from Norway was some wind.”

But necessity is the mother of invention, and in his quest to create the right conditions to capture unforgiving Hoth’s natural atmosphere, Burtt accidentally found his solution. “I was up above Pasadena at Wilson Observatory, and as I’m coming down the long 19-mile road, I found that if you just crack the window open on the driver’s side of the car and then turn the engine off and just coast, you get a whistling of wind through the window. So I did a series of what I called ‘car coast winds.’” With his foot on the clutch and a microphone pressed to the cracked window, Burtt captured what would become the base track. “We rented an old-school Mole Richardson wind machine, favored by radio programs in the 1940s, and recorded a window screen angled into a strong wind at Point Reyes in the headlands to round out the collection....I probably made a dozen or so, maybe more, versions of Hoth winds,” he says. “They went from light to heavy. We would find the right texture for each scene. They were done in stereo and they had a nice environmental feel to them. Those winds are still used today.”

The sounds of battle

When it came to capturing the sounds of the Imperial victory at Echo Base, Burtt relied on an array of real-life war machines. “We spent two weeks going out with the US Army to record all of their weapons,” Burtt says. “It was like being in basic training except I didn’t have to take orders. The Pentagon Department of Defense arranged for us to travel around and go to different army bases where we did lots of weapons -- artillery, small arms, shoulder launched missiles. And all of that munition -- the ricochets, the bullet fly-bys, explosions -- became the core material for the snow battle.”

Battle of Hoth

The sound library Burtt and his crew compiled from the American military gave Lucasfilm a distinctive weapons library that distinguished it from the well-known Hollywood standards. “You could take a ricochet of a bullet that we recorded and you could slow it down to become a really interesting laser, or an ion cannon or something like that,” Burtt says. But looking back at it, you’d be hard-pressed to get that kind of open access today to military activity because of the liability, he adds. “We had some close calls, where bullets were hitting the ground near us and passing overhead. But we got some good sounds!”

On another expedition, Burtt spent a week at the White Sands Missile Range in New Mexico, recording various target drones and rocket launches. “Those events gave us roaring jet engines and the crackling sounds of launch vehicles ascending. Smaller research rockets would be much faster and whizz by. They would launch drones and shoot them down with interceptor rockets. Those roaring sounds and pyrotechnic elements would work their way into pass-bys of ships and additional sounds for weapons. There’s numerous tripod ray guns and turrets in the Battle of Hoth that have turbo lasers on them and they all needed different and distinctive sounds. And so these things I recorded at White Sands Missile Range as well as with the army, they would end up being elements in there for those battle sounds. Recording at White Sands was really a great opportunity. We captured a collection of weapons and rockets that would be very hard to arrange, if not impossible, to do today.”

Just getting a permit to fire a single gunshot at Skywalker Ranch might now takes weeks of paperwork, Burtt says. “If we had to go through that much trouble back then, nothing would have been recorded. And so I'm thankful that we had more freedom on Empire. We were just running loose, responsible for our own fate.”

The National Air Races in Reno, Nevada provided another fertile but dangerous ground for recording. “Back at that time there were few safety restrictions,” Burtt says. “We’d be on the runway, very near the zooming aircraft. I’d say, ‘Hey, I’d like to record at the base of a racing pylon to get those 400 mph pass-bys,’ and they’d say ‘Yeah, OK. Just be careful.’ I would hike out there and crouch down on the desert floor and planes would go by just a few feet overhead. You could smell the aviation fuel. They’d never let you within a mile of those pylons today.”

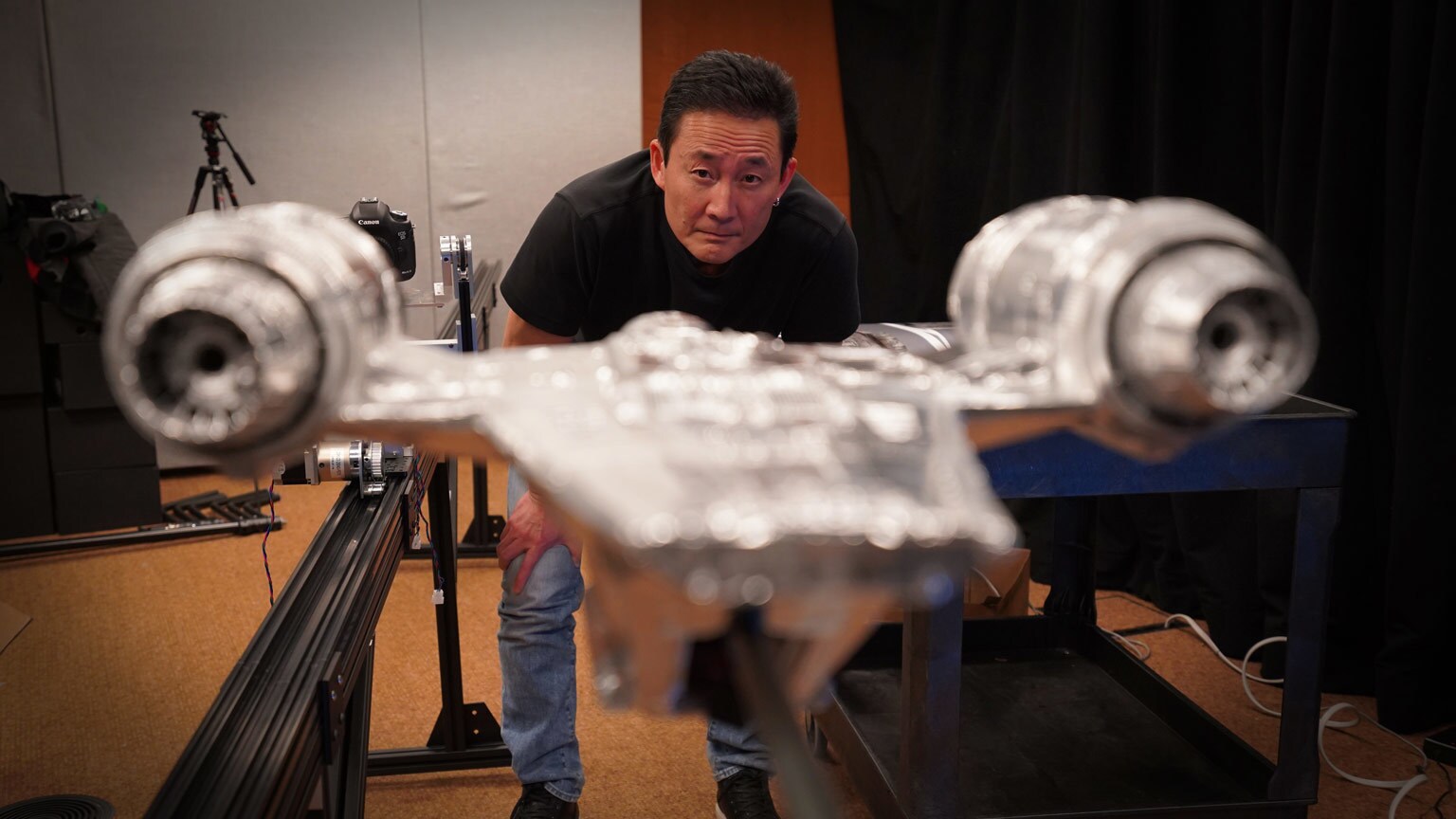

The Millennium Falcon

That close-range was essential for defining some of the most iconic Star Wars ships. “We went out and recorded all of these aircrafts, and got close perspectives. Those recordings became the basis for a lot of the new ships and Star Destroyers.” Burtt used some of the sounds to add to the initial effects he’d created for the fastest hunk of junk in the galaxy, the Millennium Falcon, and the roaring TIE fighters. We found that if we recorded a high energy piston aircraft -- a World War II type aircraft -- and slowed the recording down, you get a roar that people don't recognize. They hear a very solid Doppler Effect of something roaring by. It has a grinding energy to it, and people respond to the reality of that sound. They don't know what it is, but they realize it is real in some way, and that illusion is a key factor for all of the sound design in Star Wars.”

After all, that’s the core of Lucas’s direction for the whole of designing the galaxy far, far away. “George [said] he wanted things made out of real objects. If we went out and did documentary-type recording, by its very nature it would have an authenticity to it. It would be real things, not something just electronic on a synthesizer or theremin, which was the tradition for science fiction previous to Star Wars. That organic nature of the sound is the key basis for everything done in Star Wars. That was really George’s inspiration from the beginning so we got used to that approach.”

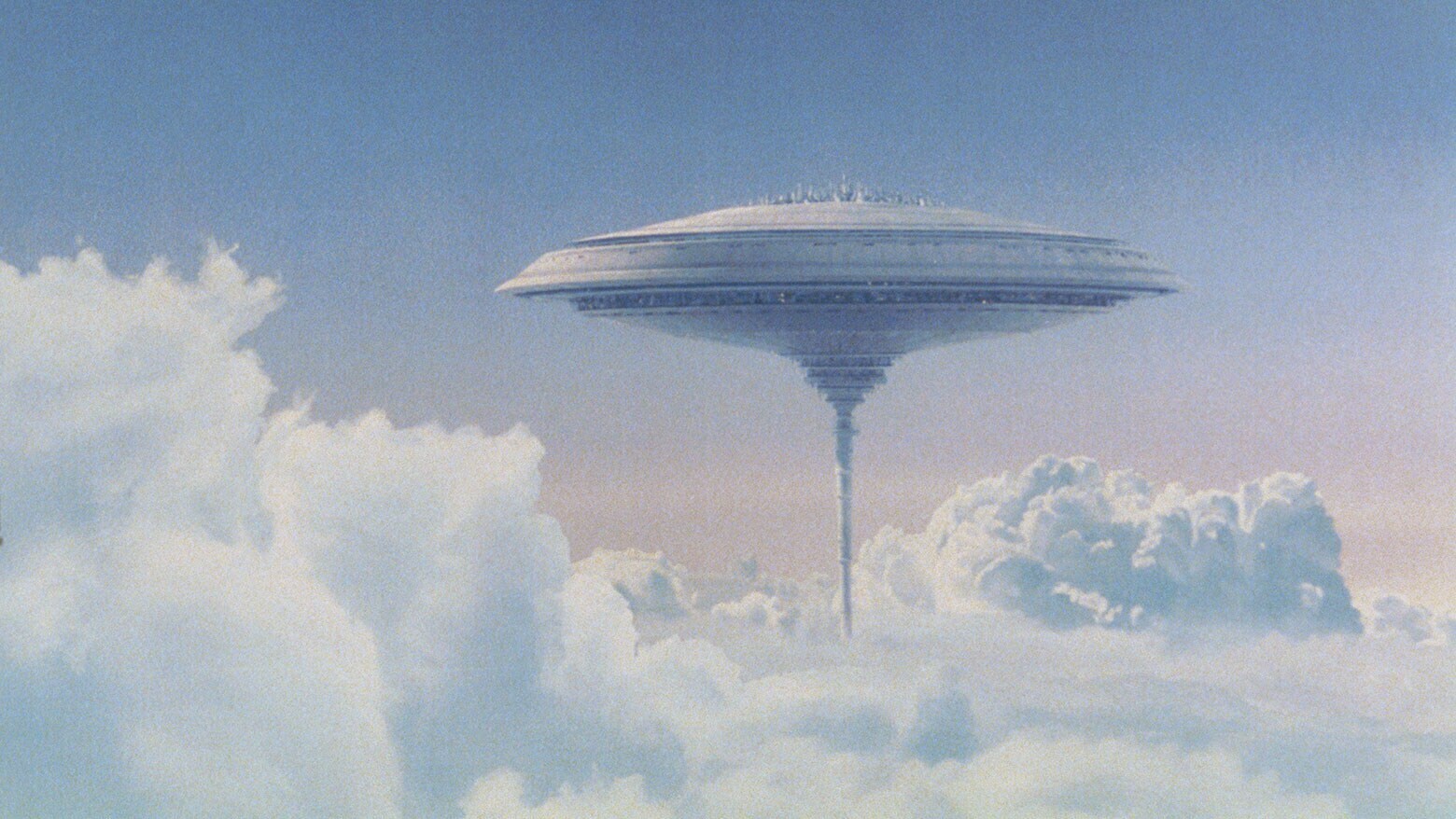

Among the clouds

In fact, many sounds like the somber fog horn of the Golden Gate Bridge -- which made it into the mix for the sounds of Cloud City in a quieter moment when Han and his friends have just arrived -- were recorded near Burtt’s home. “The trick, I guess, is taking a sound which has a perceptual familiarity and then inject it into an exotic context. It loses its specific identity," Burtt says. "What remains is just an emotional association. The fog horn has a sense of space and distance to it. Put in the soundscape of Bespin, it no longer is a San Francisco fog horn, it is just some sort of distant beacon or vehicle or something. It was the kind of sound you could put in a soundtrack and it would sit there in the background without catching too much attention… but create a sense of depth. It has a haunting feel to it, and that emotional tone is important.”

Boba Fett

Burtt and his team also worked to give a new mysterious bounty hunter, Boba Fett, his own distinctive sound akin to Darth Vader’s ventilator, although that subtle addition was barely audible in the final film. “[Boba Fett] first appeared in the cartoon made for the Star Wars Holiday Special. At the time he was introduced, we were trying to give him a distinctive ambient sound that was always heard when he was around. We had done that previously, of course, with Vader’s breathing.

“So with Boba we added some telemetry and soft electronic noises as if there were scanners or sensors onboard within him. Although we made those sounds, they were never heard because he never appeared in a quiet place,” Burtt says laughing. The sound mix would finally get its moment to shine when Boba Fett was added back into the special edition of Star Wars: A New Hope, in a quieter moment in Docking Bay 94. For the years prior, the only other place it could be heard was emanating from a special Boba Fett costume that was fabricated for character appearances. “We built a cassette recorder into his chest pack,” Burtt says. “The sounds played back on an endless loop cassette, just like they did for R2-D2 at that time, before digital technology. When Boba walked around, he always broadcast his customized sound.”

Echo Base

For an echoing work space like the Hoth hangar, Burtt relied on aircraft factory noise from hangars at Los Angeles International Airport where maintenance crews worked on the aircraft. “You went in there and there’s people hammering and sawing and using socket wrenches,” Burtt says making a zipping sound with his mouth. “Randy [Thom], he went to a lot of factories, so he would always come back with yet another of what we called industrial backgrounds. I’d clean it up and retain the parts that I liked and eliminate voices and phones ringing that were clearly audible and a distraction. Then I’d add a few exotic electronics or weird vocals and end up with something futuristic and exotic -- something that wouldn’t catch anyone’s attention, but it would have the right balance of reality and fantasy.”

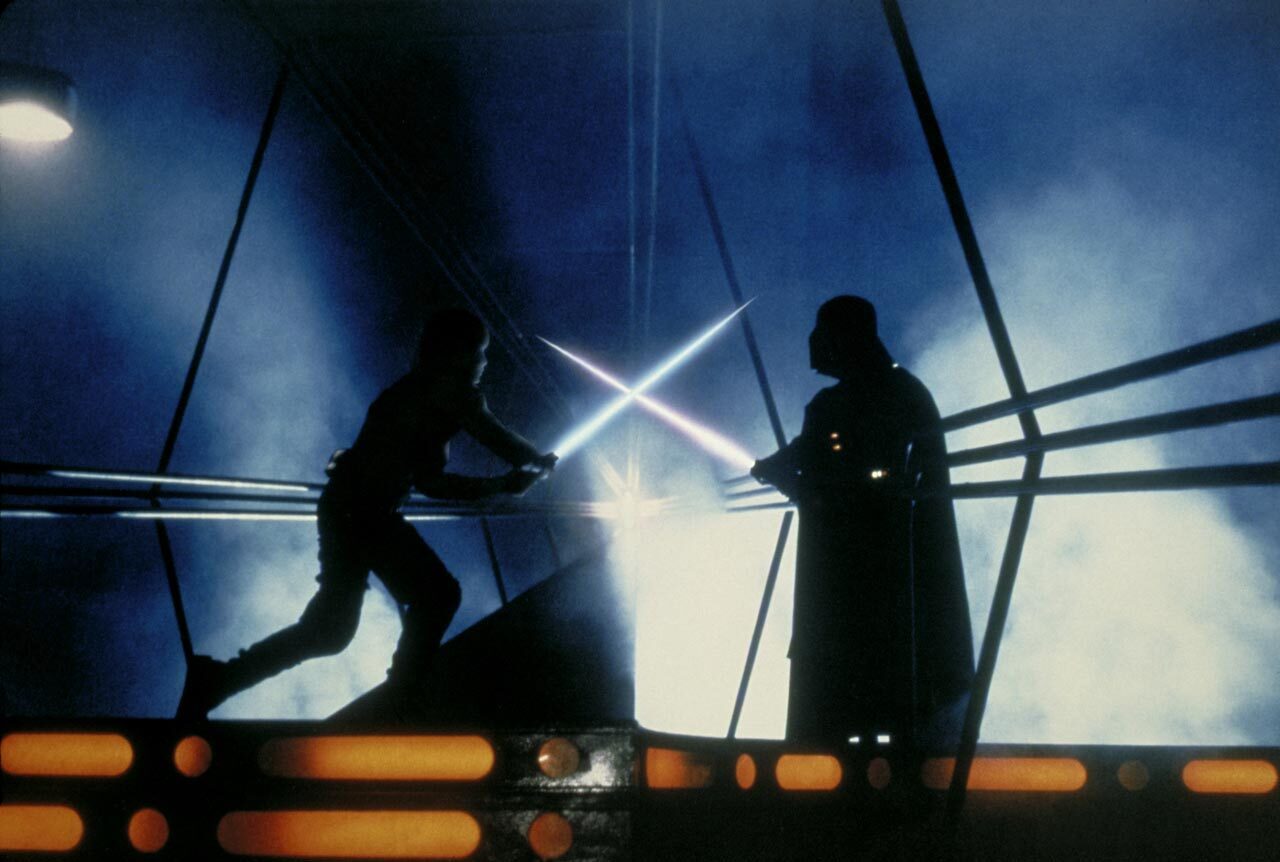

And for the scene of the film’s epic climax -- the fateful lightsaber duel inside the carbon freezing chamber and beyond -- Burtt built upon some of the sizzling sounds used for the first film but brought it to the next level. “As each movie went along, we elaborated on the basic core material because they would do so visually as well. The lightsaber fight in Empire is more extensive, and it’s faster than the one in Episode IV. Each time it would get faster or a little more exotic. But I’d always go back to the same core elements that we made for the first film. What could I do with it now that I haven’t done? Could I stretch it some more, can I make it faster somehow? Can I cut it differently? So I would just revisit and redesign each time.”

The carbon-freezing chamber

To capture both the carbon freezing chamber’s elements and the lightsabers swishing and sizzling, Burtt spent time recording the sounds of metal coins pressed into dry ice. “A coin, at room temperature, is so hot compared to the ice, that the ice melts instantly and it vaporizes. It vents gas. And it squeals, the gas escaping from under the coin -- just like the sound you make when you pinch the nozzle on a balloon as air escapes through it.” The track is punctuated by variations of a carbon arc light burning. “The other sound which was used for lightsaber hits is a carbon arc ignition. Carbon arc lights -- which don’t really exist anymore because they give off toxic fumes -- at that time if there was a big searchlight somewhere for a movie premiere, a giant bright light, it was a carbon arc light. Inside were two rods of carbon with gigantic voltage applied, and when the tips of the rods were brought together a spark jumped and they burned. You can vary the sparking effect by moving the rods back and forth in near contact. To safely collect the vital effect, Burtt traveled to a company that serviced the lamps. “We had them play around with their carbon arc ignitions, pushing and crunching the rods together, and do things that you ordinarily wouldn’t do, just to see what sounds could be produced: The result was a lot of squeals, zaps, and explosive buzzing. The machinery running the carbon arc lamps were also a useful source. There was a motor which slowly pushed the rods together which had a clanking sound. That became the general ambiance of the whole chamber. I made almost everything in the carbon freezing chamber out of those carbon arc light sound effects,” Burtt says. “It’s interesting what came out of that expedition. The squealing, slowed way down, was used when they put Han into the carbon freeze.”

To create variations of Luke Skywalker and Darth Vader clashing sabers, “I had to go back and expand the original catalog, making it more vigorous, more dangerous sounding,” Burtt says. “I would try speeding things up and I would try distorting it in different ways. I would crank out new material, and keep doing that on each film as fights were getting faster and more intense!”

The Empire Strikes Back remains the most stressful and exhausting film Burtt has worked on, but also one of his favorites. “From an aesthetic standpoint, I really love that film. There are some great moments in it -- the carbon freezing chamber, the snow battle, Dagobah, those are all fun moments. The sword fight between Luke and Vader, especially. There’s a whole section without any music so the strength and detail in the sound design could have a moment of stardom. We were riding high, then, and the team did a magnificent job.”