On May 21, 1980, Star Wars: The Empire Strikes Back made its theatrical debut. To celebrate the classic film’s landmark 40th anniversary, StarWars.com presents “Empire at 40,” a special series of interviews, editorial features, and listicles.

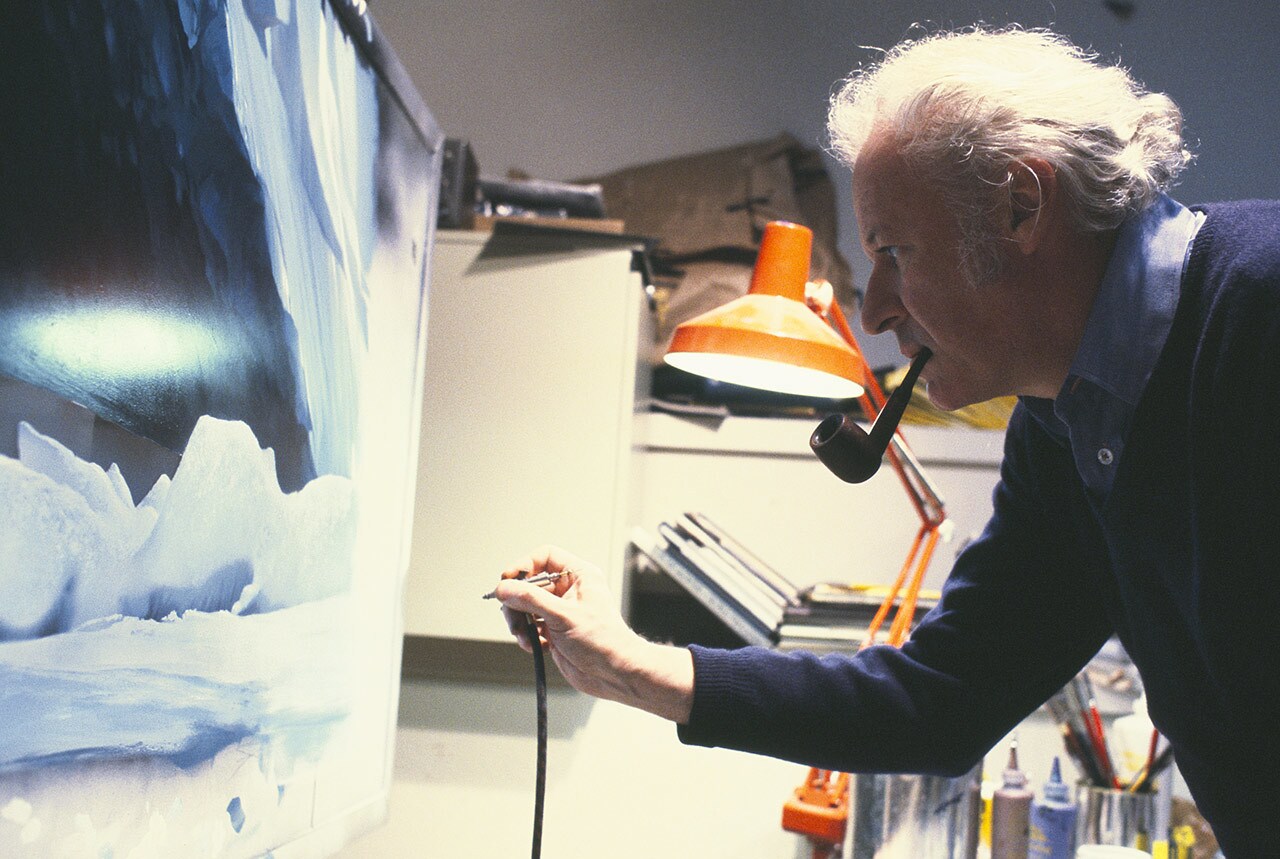

Seventy matte paintings were created for The Empire Strikes Back by three artists from Industrial Light & Magic (ILM). Two of them, Ralph McQuarrie and Michael Pangrazio, were relatively new to the art form. The other, Harrison Ellenshaw, had practically been raised for the task as the son of Walt Disney’s chosen matte painter, Peter Ellenshaw.

Using acrylic and oil paints, some mattes were fragments to complete an existing shot, others were full windows into a galaxy, and quite appropriately, all of them were painted on framed, rectangular glass (a favorite ILM story recounts that shower doors purchased from hardware stores made the best canvas). It’s a precise art, to say the absolute least.

The matte department had its own studio on the second floor of ILM’s “Kerner Optical” facility in San Rafael, California (where even the slightest shakes in the building could affect a shot-in-progress). To create many of the effects, the paintings were combined with elements front-projected onto the clear or neutral areas of the painted glass. Neil Krepela and Michael Lawler were the matte photographers, assisted by Craig Barron and Robert Elswitt (the former just 18 years old). Here are the stories behind five of our favorite matte paintings.

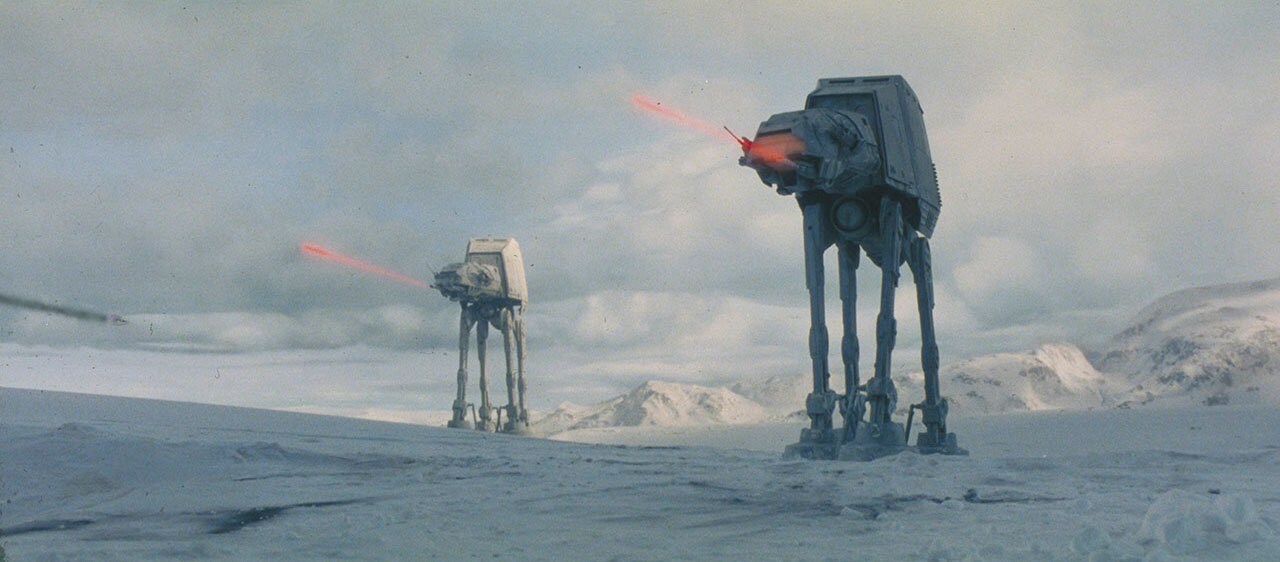

1. Backdrop to a Battlefield

Complications with blue screen photography led the ILM artists to go with a classic technique for the Battle of Hoth, inspired in part by Willis O’Brien’s work on King Kong (1933). The stop motion AT-ATs and other animated models would be photographed directly in front of painted backgrounds. Michael Pangrazio, at 21 years old, was the chief artist for these paintings.

Working from reference imagery of the Norwegian filming locations, Pangrazio’s work was more akin to traditional Hollywood backdrops than modern visual effects mattes (the largest was 35-feet-wide). Though physical backgrounds had become somewhat passé at the time, effects supervisor Dennis Muren explained to Cinefex magazine, “that’s just because they don’t have the right artist to do it.” Pangrazio also created foreground paintings which were physically shot on glass in front of the models to lend additional realism.

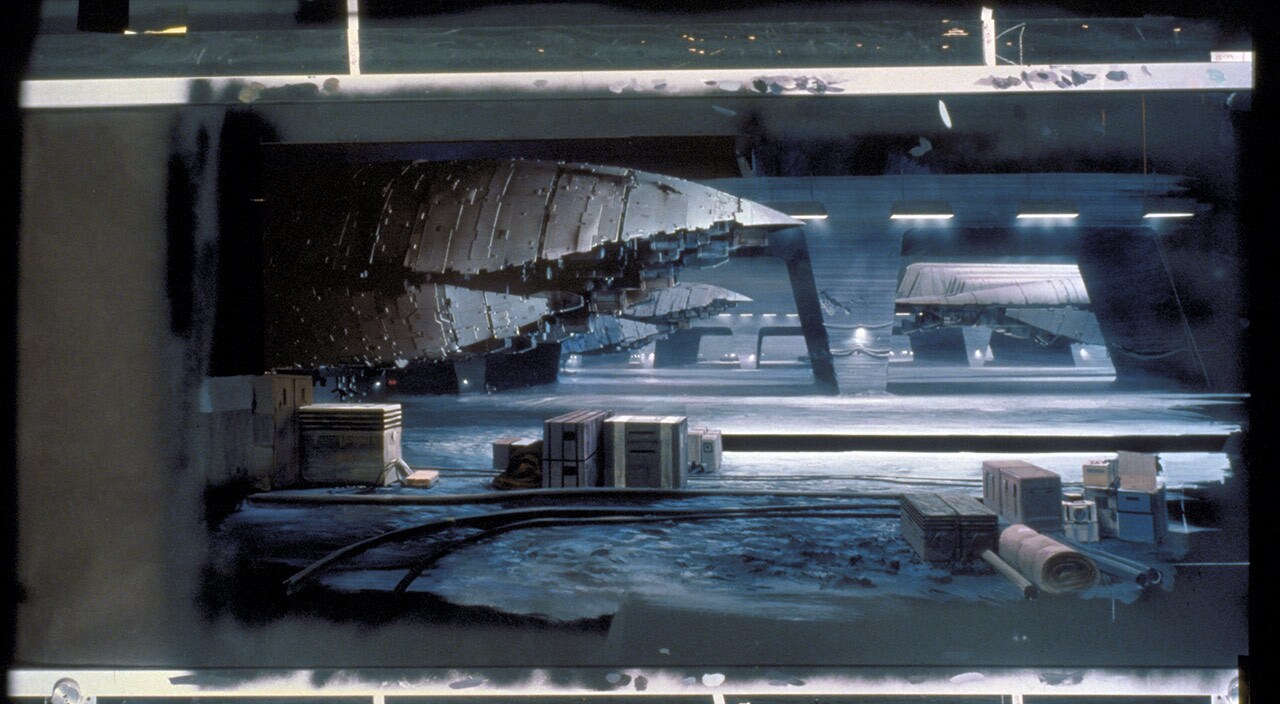

2. No Transports Are Away

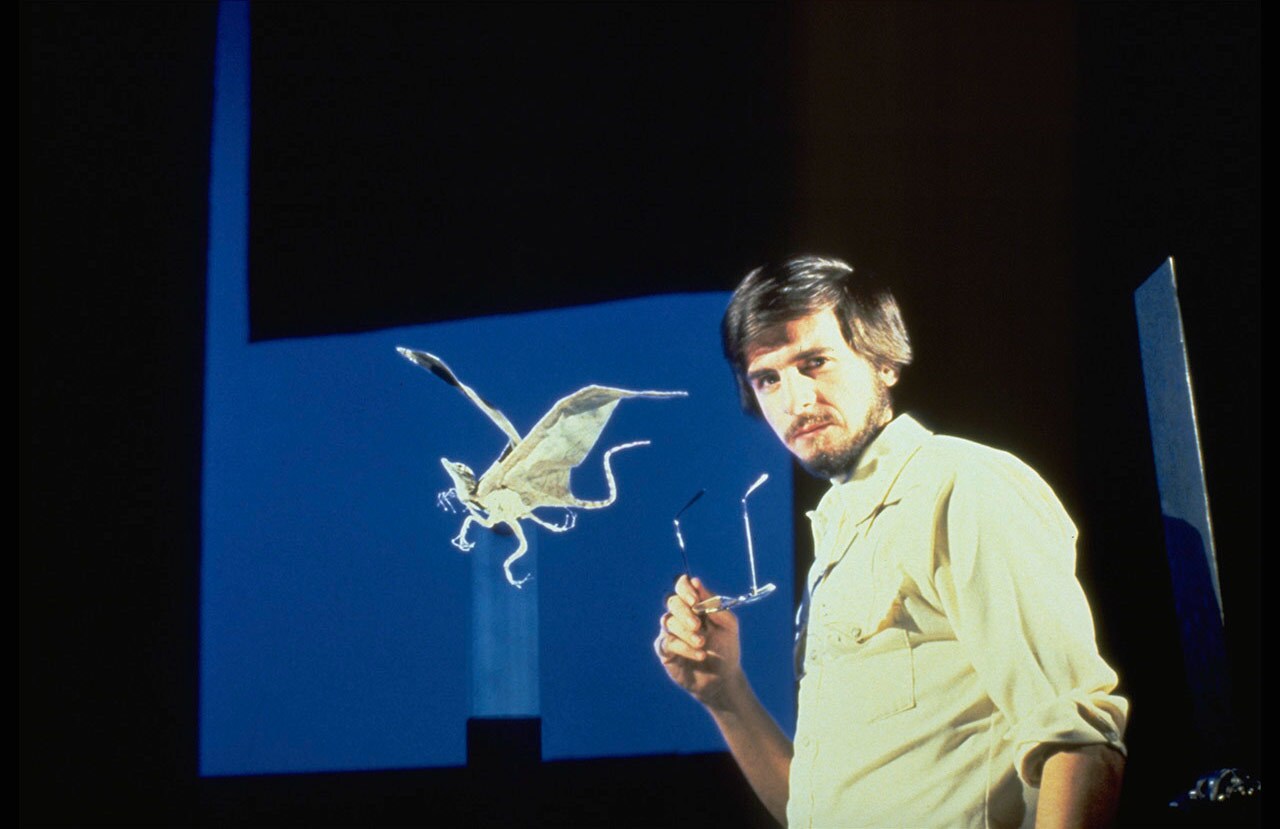

Though an accomplished artist, Ralph McQuarrie had little experience painting mattes. The department needed additional help to meet its deadline, so he joined the marathon six-day work weeks, and helped mentor the young Pangrazio. McQuarrie was happy to create paintings that would be directly photographed and visible onscreen, unlike his conceptual art.

This view of the Echo Base interior evokes the same composition as one of McQuarrie’s concept paintings, with increasing levels of depth. In the final matte, the X-wings and Millennium Falcon are replaced by the rebel transports, the only time they’re seen hangered within the icy stronghold. The live actors in the foreground (played by art director Joe Johnston, Harrison Ellenshaw, Michael Pangrazio, and effects editor Michael Kelly) discuss the plan to evacuate. McQuarrie himself is seen crossing from right to left, portfolio in hand, dressed as a rebel general. “It was kind of neat to have the guy who actually did the painting moving around in front of his own work,” effects supervisor Richard Edlund explained to Cinefex.

3. Welcome to the Swamp

Soon after completing Empire, effects supervisor Richard Edlund noted this establishing view of Dagobah by Harrison Ellenshaw as his favorite matte painting in the film. “[…] It’s all [a] painting except for a little foreground water with some fog,” Edlund told Cinefex. “All we added was the smoke coming out of the X-wing, and the birds which were animated.” It’s a moment when effects take center stage, courtesy of ILM and Sprocket Systems (later renamed Skywalker Sound). Dagobah is introduced as a world equally frightening and alluring.

For Ellenshaw, this was one of the largest paintings he created for Empire, with half his time usually consumed with supervising the matte department. Small puppets were made by Phil Tippett for the bird creatures, then animated in stop-motion by Ken Ralston on the ILM night crew, whom Ellenshaw later described to former Lucasfilm executive editor J.W. Rinzler as “a crazy group.”

4. Hasty Departure

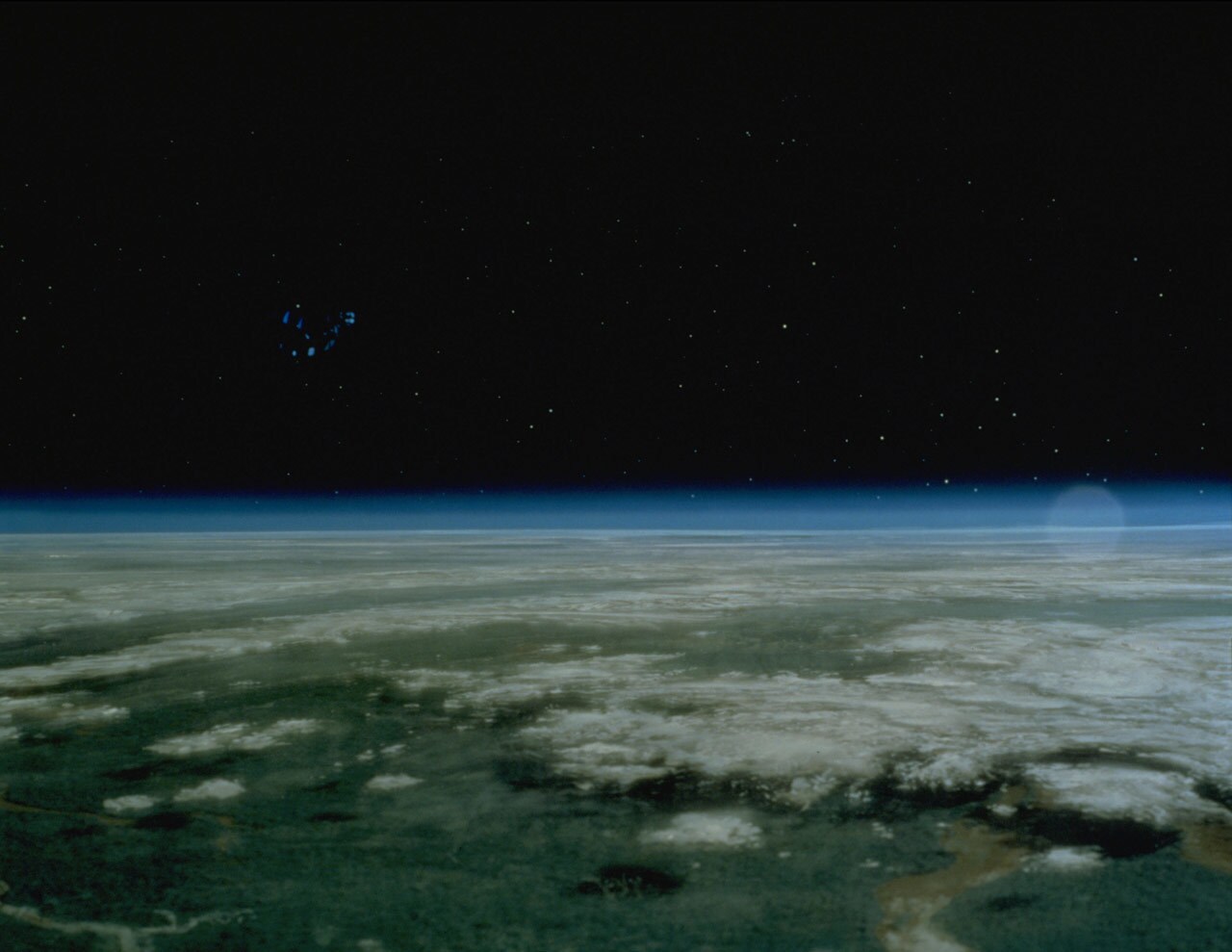

With increasingly tight deadlines, art director Joe Johnston stepped in to help Michael Pangrazio paint a low-orbit view of Dagobah. This served as the background for Luke Skywalker’s X-wing blasting off into space on its way to Cloud City.

The effect actually required two paintings: one of the greenish-brown planet, the other a thin layer of clouds on plexiglass. Perpendicular to the camera’s view, the clouds were placed inches above the planet, creating shadows across Dagobah’s surface. The photographed illusion was very convincing.

5. Stick the Landing

Decades before computer graphics effects allowed ILM to realize Coruscant, Cloud City was a difficult metropolis to visualize. An expansive model had been considered, but there was little time to build one. The bulk of the task fell to Ralph McQuarrie, who created a series of views of the city, including a painstakingly detailed wide shot of the Millennium Falcon on the landing platform.

Director Irvin Kershner noted it as one of the most complex shots in the entire film, with live-action footage shot at Elstree Studios across 64 feet of stage space, which was then combined with ILM’s matte painting. Each element of the massive shot was “all done inside a studio,” as Kershner explained to unit publicist Alan Arnold, from England to California. McQuarrie was flexing his muscles with the mesmerizing sunset scene. “What I loved so much about the exterior of Cloud City,” Harrison Ellenshaw would later say in a behind-the-scenes featurette, “was the subtlety of the sky [and] of the lighting. Elegance is what it’s all about. Very few people can pull that off, even today with CGI.”

By February 1980, the matte department began working 24-hour shifts just to complete their work on time. George Lucas stopped by almost daily to check in. The schedule inched closer and closer to the May 21 release, but at last, every painting had been finished and photographed. After Empire, Harrison Ellenshaw returned to Disney where his next effects project was a forward-thinking adventure, Tron. Michael Pangrazio rose to supervise matte painting on future ILM productions before continuing his career at other visual effects studios. And Ralph McQuarrie, well, he continued as an irreplaceable force in Star Wars visual design.