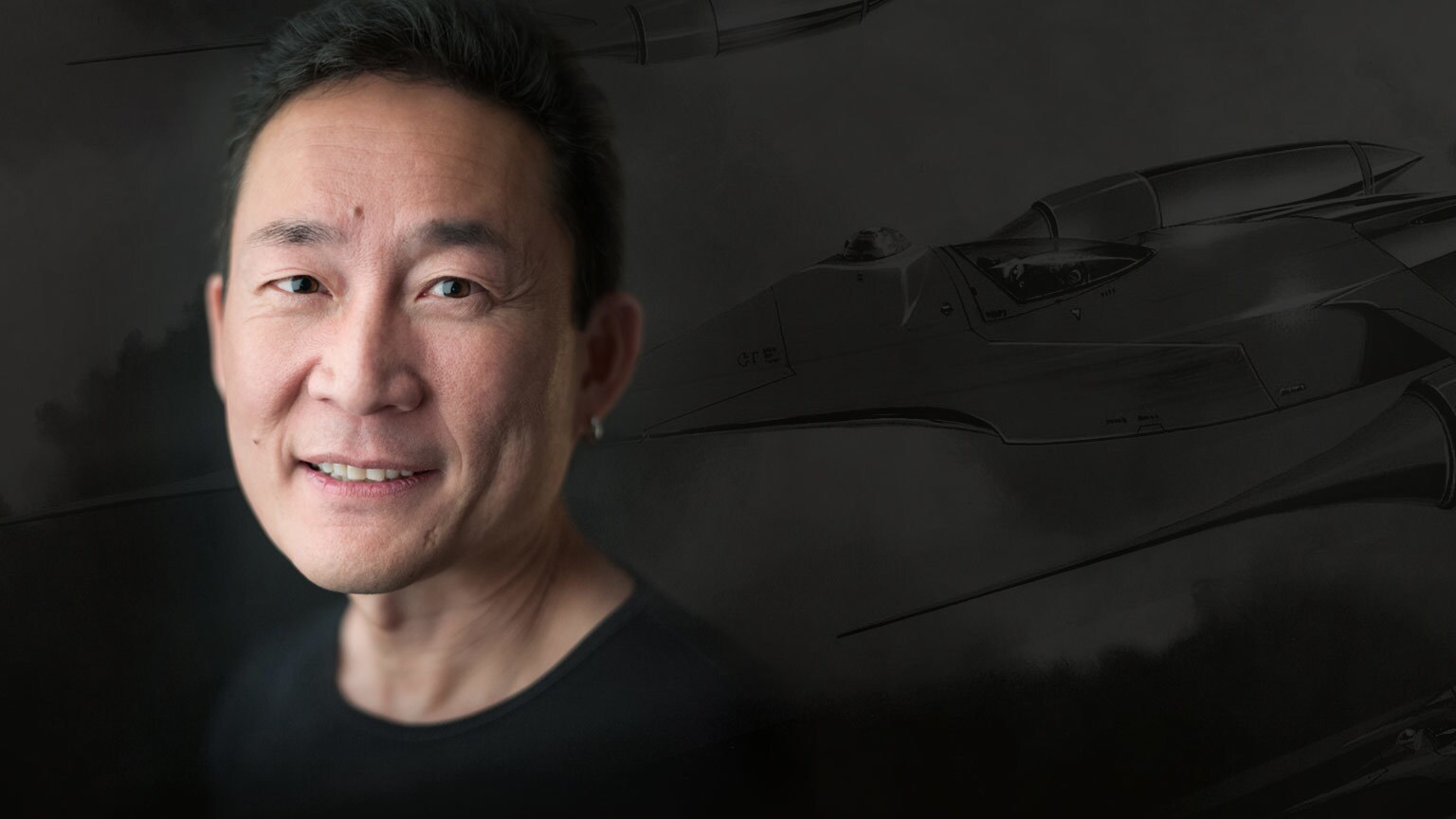

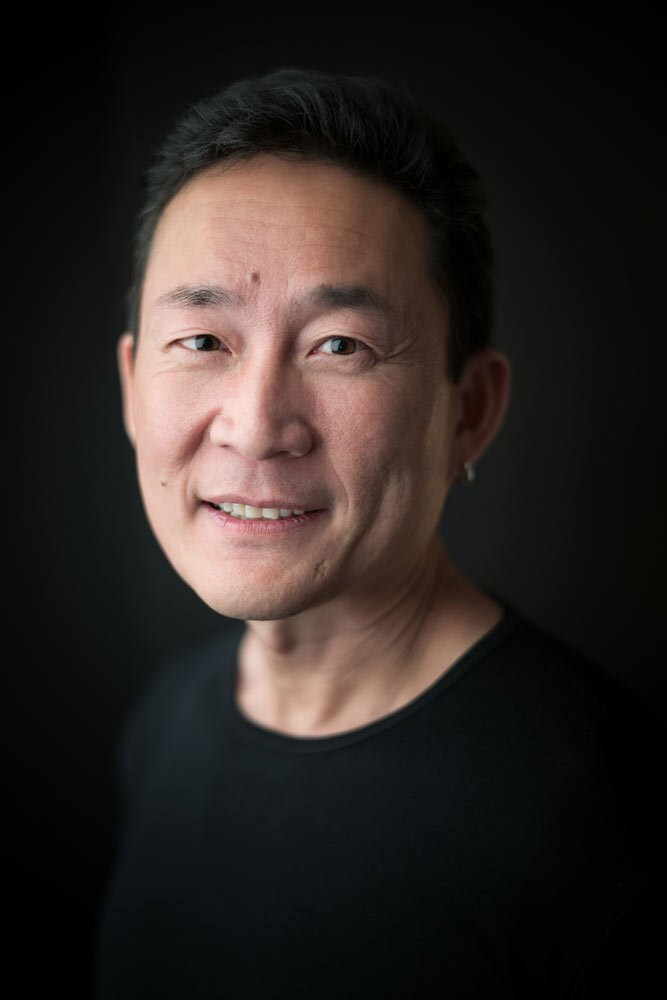

Doug Chiang is a name familiar to fans of the Star Wars galaxy. Personally selected by George Lucas, his influence as the head of the Lucasfilm art department during the production of Star Wars: The Phantom Menace and Star Wars: Attack of the Clones is legendary. Now as vice president and executive creative director at Lucasfilm, Chiang oversees designs for all new Star Wars franchise developments, including films, theme parks, games, and new media.

While his career achievements are extraordinary, Chiang graciously agreed to speak openly with StarWars.com for Asian Pacific American Heritage Month about something else: his life experiences as an Asian American. An Asian American myself, we engaged in an honest discussion about family, culture, and hardships, and talked about his humble beginnings drawing stick figures in the dirt as a child, the impact of recent hate crimes against Asian Americans on his family, and how he finally accepted his cultural identity along the way.

StarWars.com: In Asian American culture, family usually plays a big part in all aspects of life. Can you tell me a little bit about your childhood and how you grew up?

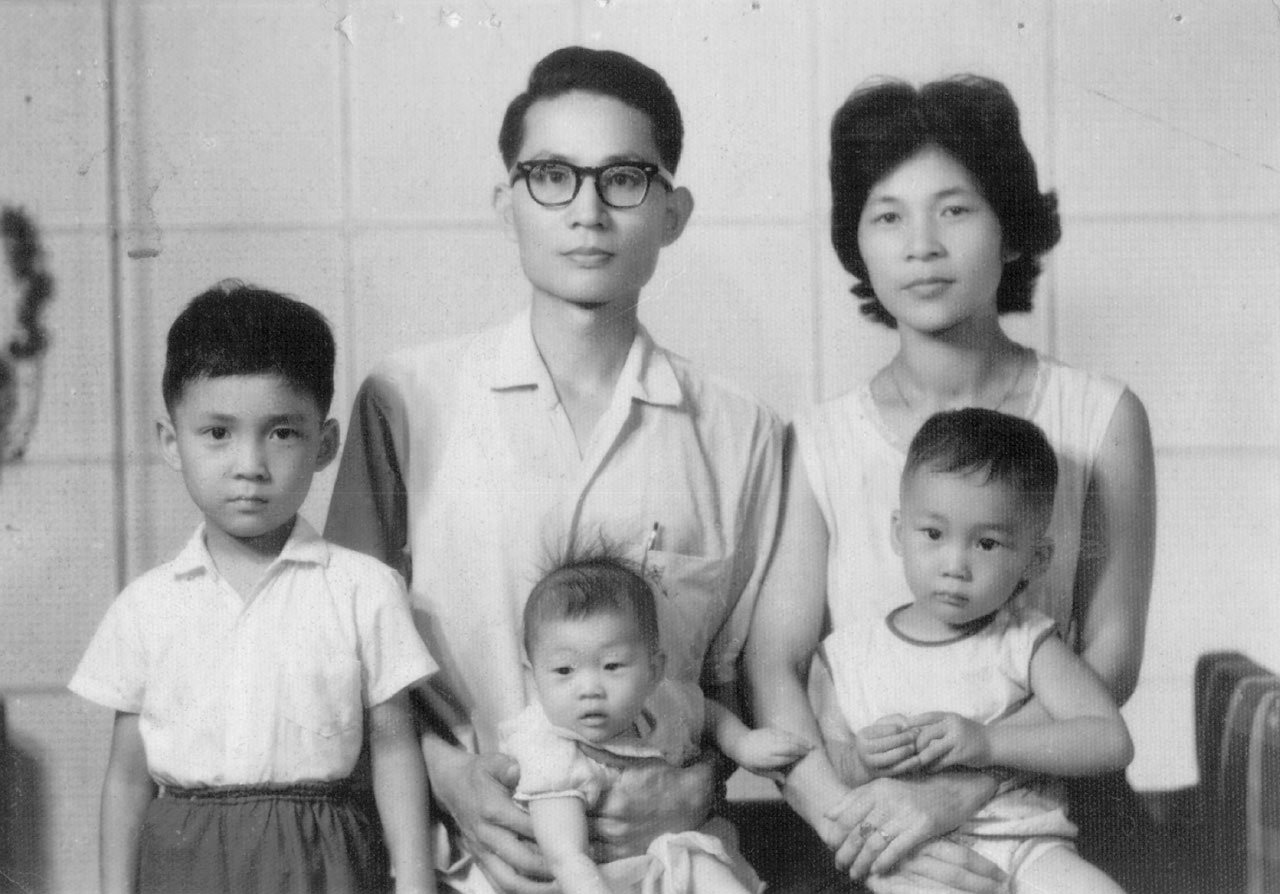

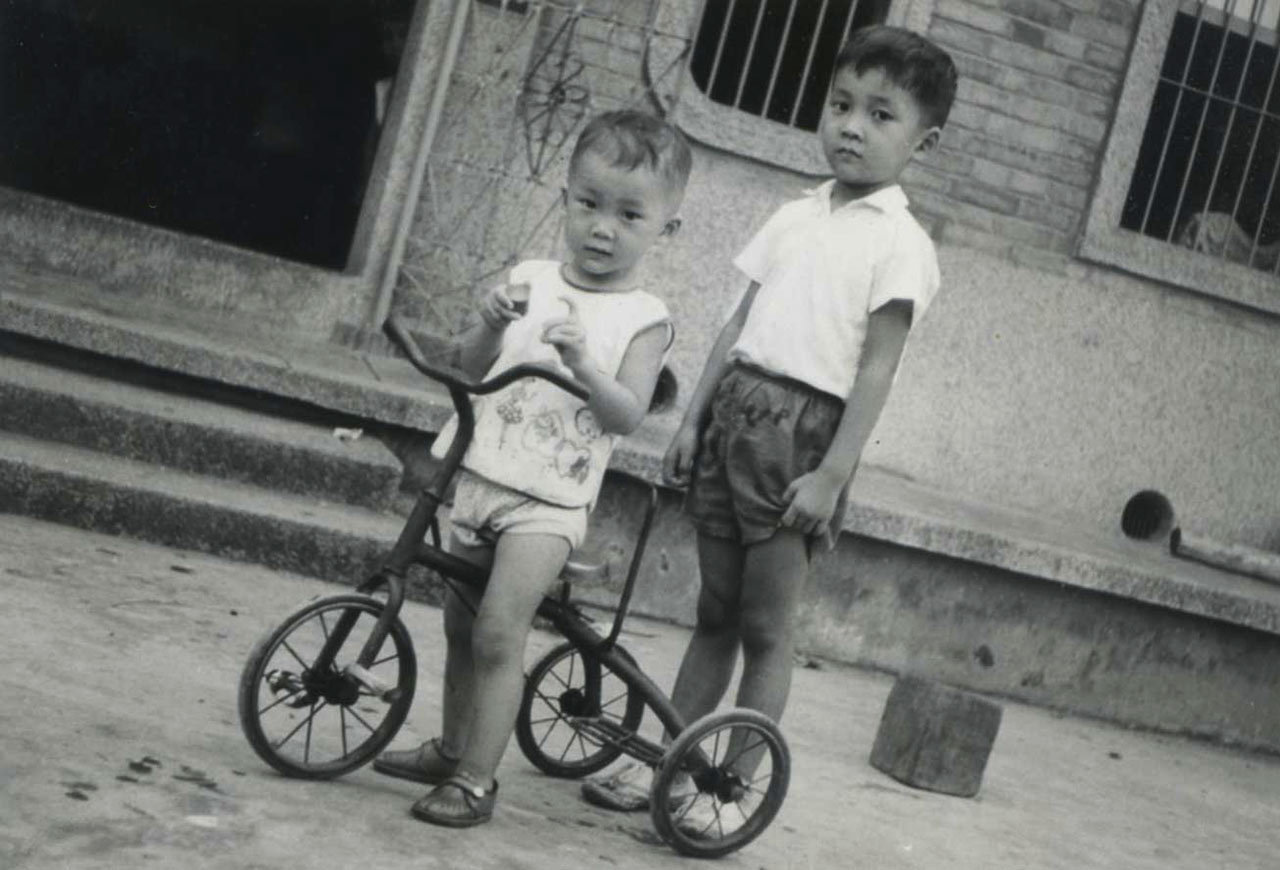

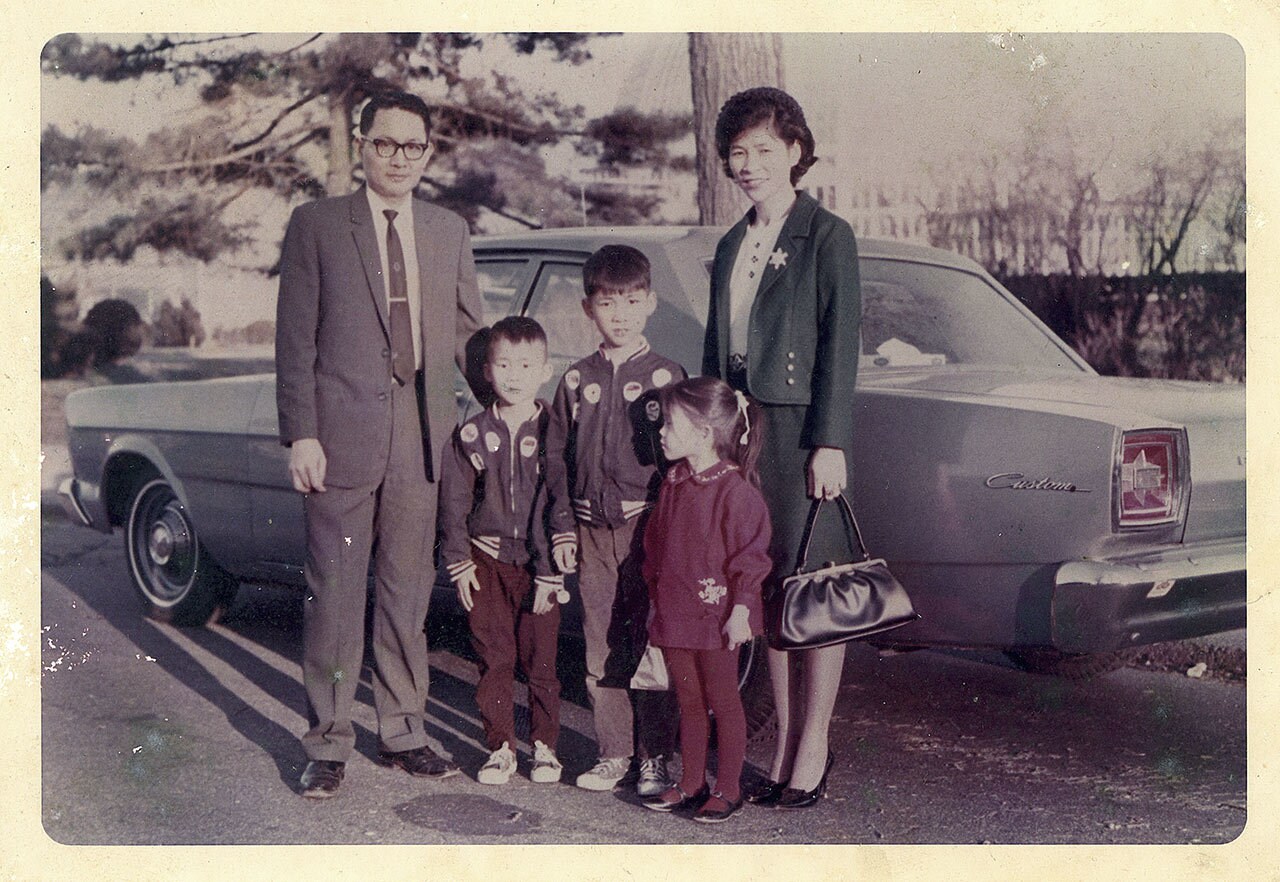

Doug Chiang: I was born in Taiwan. My parents, my dad specifically, moved over to the U.S. to go to college. Basically, to find a better living for us. He brought us all over to Michigan when I was about five years old. So I have very little memory of Taiwan. I remember going to preschool and going to some of the things we had enjoyed there in terms of where we lived. We were farmers, essentially, [on] my dad’s side of the family.

So when my dad brought us over and settled in Michigan, it was a complete eye-opener for me. I was shell-shocked -- the classic story. We came over in the middle of winter and I never experienced snow before, because Taiwan, as you know, is very temperate. That was kind of a shock. The hardest part for me, honestly, was trying to fit in, because at that time I didn’t have any idea of other cultures or anything. I just grew up associating with my family.

I remember one of the very first days when I went into kindergarten. This was in Dearborn, Michigan. It was so strange to see everybody; that was so alien to me. Alien because they looked very different from me. I didn’t quite know what that was, it didn’t really click.

I would say that one of the earliest memories that I had of American culture was back in Taiwan. We were getting our immigration papers. I remember, we went to the U.S. embassy, and there was a Caucasian American there. I remember I just stared at him because he was so different looking from anything I had seen before. [Laughs] That memory just stuck with me. It was like, “Wow! This is kind of fascinating for me.”

So when I went to Michigan, it was all of that. We grew up the classic Asian family. We were very quiet in many ways. I think that compounded the issue for me. I was very quiet. I didn’t quite fit in. Even though I was completely welcomed, it was a challenge. Our family back then, I think this was in 1967 or 1968, we were one of the maybe one or two Asian families in Dearborn, just outside of Detroit. It was very unusual.

I knew I was different. I didn’t know why. Later on we moved over to a different suburb, Westland, Michigan, and that’s where I grew up. I went to elementary school [through] high school there. I have to say, it was very challenging.

My parents really encouraged us to assimilate as quickly as possible, meaning to learn English and to not speak Chinese. Even though we spoke Chinese at home and I could understand it, we didn’t really continue it. In hindsight, that was kind of sad for me, because I forgot Chinese. Ironically, I can understand my parents, because they speak it very distinctly in terms of Taiwanese and a little bit of Mandarin. But only when they speak it. [Laughs] I remember we went back to Taiwan 20 years later and we met our extended family. I couldn’t understand them even though they were speaking the same language! It was so bizarre. I had gotten so used to how my parents spoke.

So one of the things that we did was really try to fit in very early on. Speak English, culturally try to fit in as much as possible, and in some ways, try to hide or suppress our Asian culture.

We tried very hard to fit in right away in terms of how we dressed, how we spoke, how we socialized. But then on the inside -- our family lifestyle -- it was still very culturally Chinese, in the sense that our parents imbued really strong work ethics. They wanted us to work hard. The classic thing -- overachievers, really wanted us to succeed. They pushed us pretty hard in that respect.

StarWars.com: That family dynamic, I think, is prevalent in many Asian families and Asian cultures. I got my start with a degree in architecture, actually, so my path has been widely varied. But the need to create has always been a part of who I am. Was your family supportive of your career in an artistic field given that they were so strict about grades?

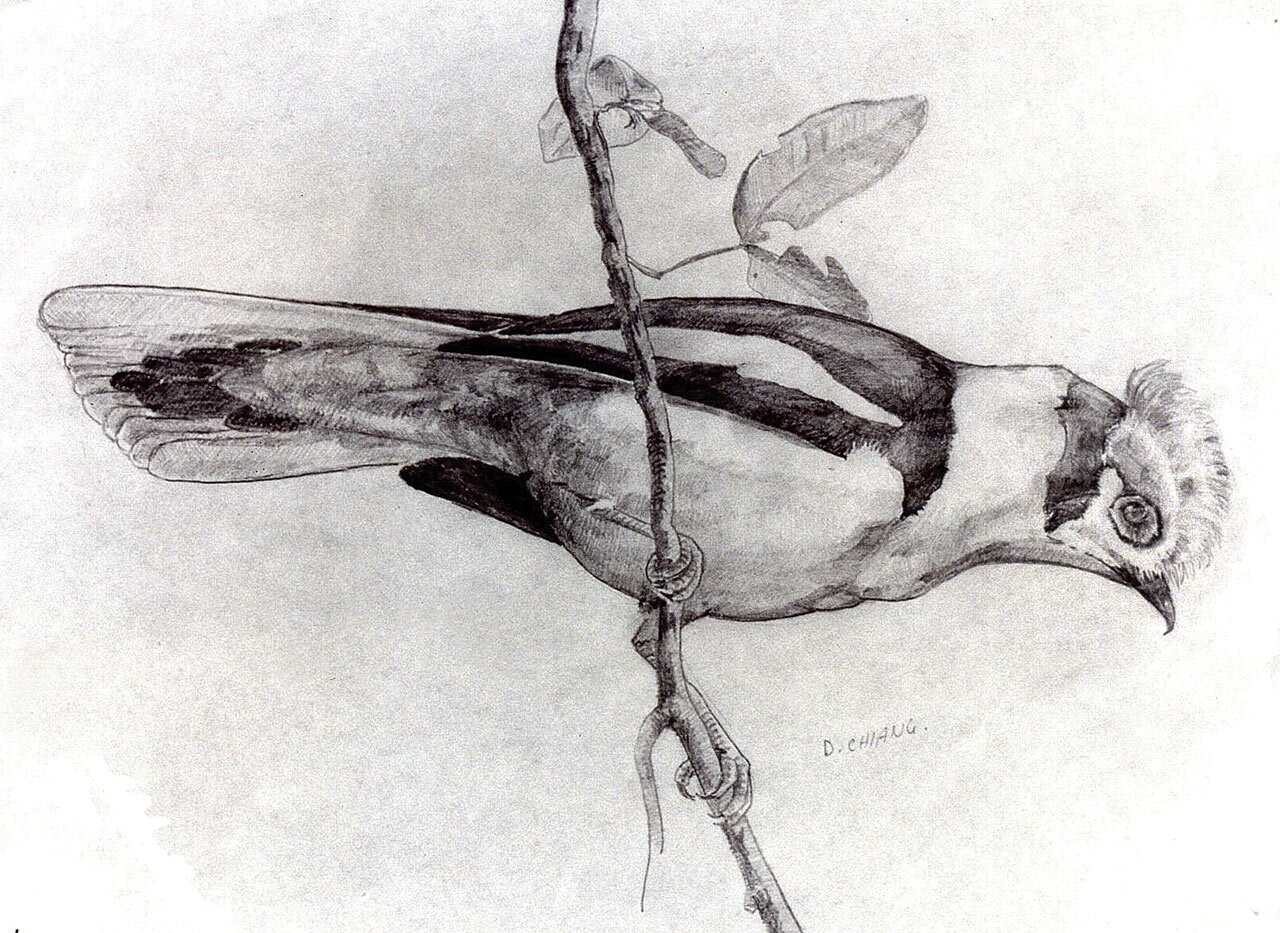

Doug Chiang: [Chuckles] Not right away. I have an older brother who’s four years older than me -- he kind of plowed the path for me. He had a hard time. Both he and I drew quite a bit. I remember one of my first drawings was just stick figure drawings in the dirt in Taiwan, because we didn’t have paper. I would draw all the time. I would draw these epic stick figure battles in letters that my mom would write to my dad when he was in college in the U.S.

So I’d always drawn. I didn’t really know if that would be a career. I remember both my brother and I had a passion for art. He was actually quite good, much better than I was. Early on, he expressed to my parents that he wanted to possibly pursue a career in art. I remember he got a lot of resistance. It was the classic thing, you know. They wanted us to be engineers or doctors or lawyers. Art was really not encouraged. There wasn’t really a future in that.

When it came to my turn, it was hard in the sense that art was my way of escaping and fitting in in elementary school and high school. Because I was so different and because I was quiet, art was the only way I could actually get any kind of respect. So I really just drew a lot, not knowing what kind of career I would have. It was more of an enjoyment.

Part of it, also, was to escape my world. I just decided it was easier to create my own world, create my own characters. Unknown to me at that time, I was really doing a lot of that worldbuilding on my own, out of self-preservation in some ways. It was actually very successful in that.

I think the biggest turning point is that I discovered filmmaking. In my parents’ eyes, filmmaking was slightly different than fine art or design, because they didn’t quite understand what it was, so I think they gave me a little bit more wiggle room in that. [Laughs]

Specifically, I remember my passion for film developed after I saw Star Wars and The Golden Voyage of Sinbad from Ray Harryhausen. Those two films, when I was about 14 or 15, really sparked my imagination in terms of worldbuilding. They were very much in the same world of the drawings that I was doing. I was creating exotic worlds and characters. I really didn’t have a way to express that fully, and I didn’t know there were actually people doing that until I saw those films.

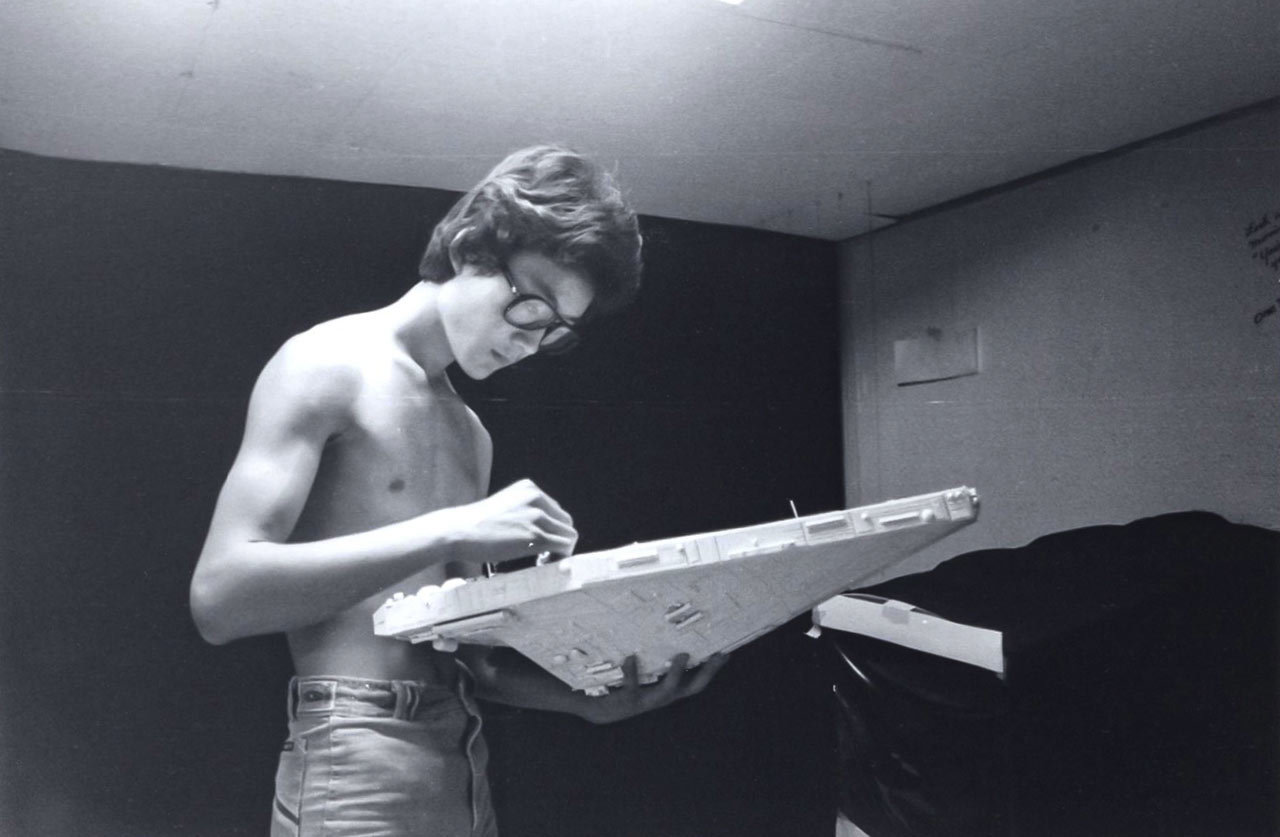

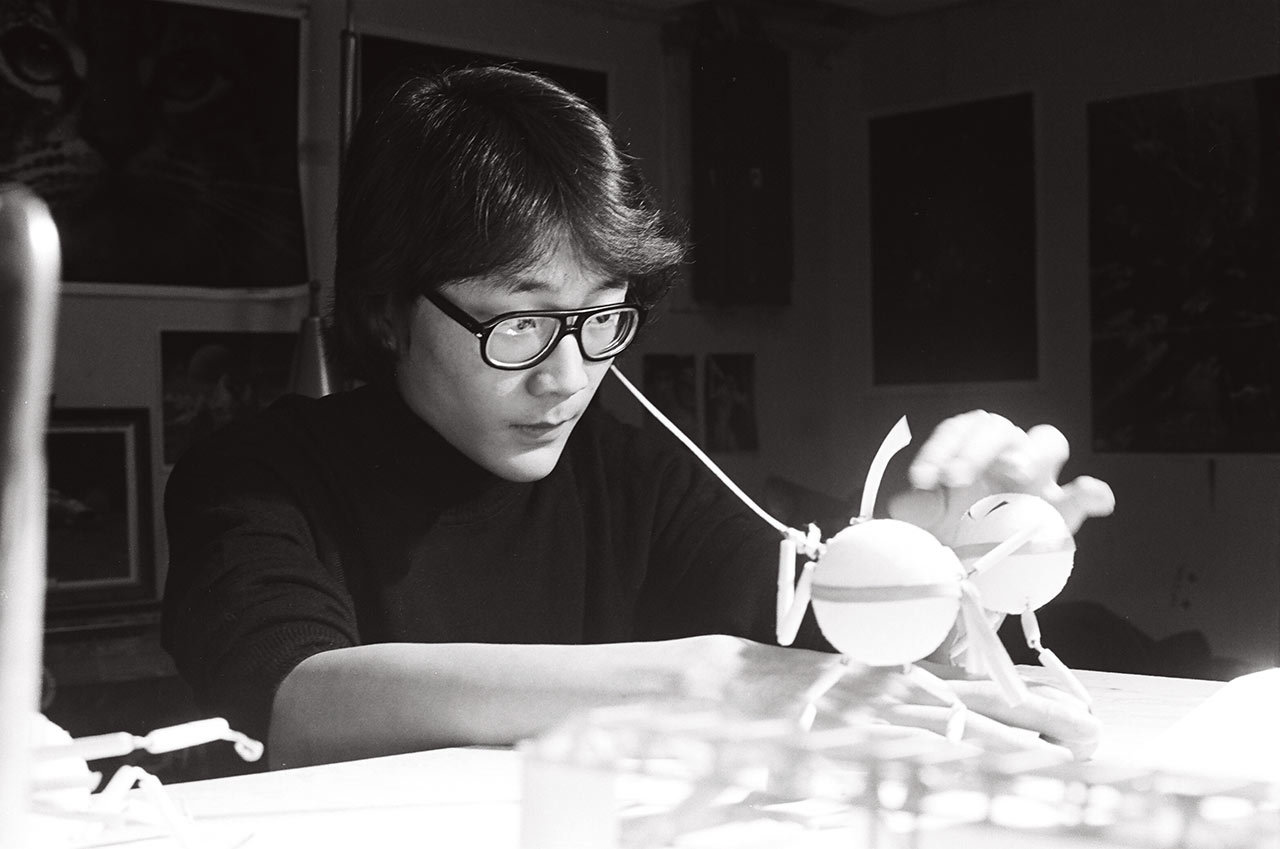

When I saw those films, what I realized was that that could be a potential career. And then the following year after Star Wars, I saw The Making of Star Wars, and that completely transformed me. That’s when I saw people behind the scenes, doing the craft, doing the artwork, doing the model building. I knew. I said, “That’s what I want to do.” That was exactly what I wanted to do.

It was still hard. I remember I didn’t really broach the subject with my parents because I just knew that they had other ideas for me. My backup plan was that I could go into science and zoology because I loved animals and nature. That was my back-pocket thing.

What changed for me was, after I saw Star Wars, I started making Super 8mm films in the basement of our home. They were short three-minute films of stop-motion animations. I would come up with the stories during the week and then I would film them over the weekend. Then it would take two weeks for the film to come back. [Laughs] But the surprising thing was that I entered them into film festivals, and I started winning them. It was a complete shock to me because I had no expectations of any of that.

I was starting to get a lot of recognition from our community for what I was doing. My parents saw that and probably thought, “Okay, maybe there is a potential career here.” Even though they didn’t know what it could be, and I didn’t know what it could be.

StarWars.com: That’s so interesting. And playing off that, that escapism and assimilation of trying to fit in, I’m fourth generation Japanese American. It’s a little bit of a different experience, but I was still torn, growing up, between understanding my heritage and being seen by others as not [being] American enough. You can’t change your appearance. It was a long journey, but I eventually embraced being Asian. It took a really long time because I was doing the same thing as you -- trying to fit in and not really talking about my culture. Now it’s such an influential part of my work. Can you tell me a little bit about your path and what being Asian American means to you?

Doug Chiang: Yes. For the longest time, I tried to suppress it. If you look at our old pictures, I was the classic Asian nerd. I was very thin. I was small. I actually had glasses with the tape down the middle. [Laughs] It was everything cliché that you would think about. It was really hard for me because, obviously, I was bullied quite a bit and I didn’t have many friends. Physically, I was too small in stature, and then mentally I just felt very alienated because I knew I was different.

So growing up, it was one of those things where I didn’t have any real strong Asian role models to look up to. When I got into high school, the amazing thing was that the shop teacher was Japanese American, a teacher named Tom Nakamoto. He was really well-respected. He was liked by everybody because he was the shop teacher. He was one of my first role models because I finally saw somebody who looked like me who was actually being respected by the kids. So I tried to be like him as much as I could.

And then the other person, being in Michigan, there was a scientist named David Suzuki in Canada, and he had a series that was on TV. I remember seeing him on TV gave me hope that there were other Asians that could actually be in leadership roles. Between Tom Nakamoto and David Suzuki, those became my aspirational leaders in terms of who I could model myself to be.

But even then, it was still challenging because they weren’t really following the career that I wanted. At least I knew there was hope in terms of what that is. I remember when I first came out to UCLA to study film, we drove cross-country and I remember coming to LA. It was a complete culture shock for me. It was filled with Asian Americans and African Americans and people of all different cultures. I had never really experienced that before.

It felt really comfortable. I remember during my orientation at UCLA there were student leaders who were Asian American. I had never seen student leaders take a leadership role, especially Asian Americans, before. It opened my eyes and [I] realized, "This is what I’ve been missing out. This is what I needed." It was such a refresher for me, that there was a whole world of possibility that I’ve been subconsciously suppressing for so long, but now it was here and it was being embraced.

StarWars.com: That’s so interesting because my role model was also my shop teacher. [Laughs] He wasn’t Asian, but there’s something about those shop teachers. They really know what’s going on and they tap into your creativity.

There’s something about college, all these cultural clubs that they have. That really helped me, too, and made me realize it’s okay to be myself and find out about other people. Did you join any of those clubs in college, as well?

Doug Chiang: I did, and that was one of the most interesting aspects for me, going to UCLA. I joined and was actually one of the founding members for the Association of Chinese Americans at UCLA. It’s now grown quite large, but we were, at that time, maybe 20 students. There was the Chinese American Association, but those were mainly mainland Chinese. There was nothing for first-generation or second-generation Chinese Americans like myself.

That was one of those cases where, walking around campus, it was fascinating to me to run into and meet and make friends with Asians who were very outgoing, who were funny, who were everything I wasn’t. I didn’t realize that was normal. Growing up in Michigan, we were all very quiet, so I thought Asians are just normally quiet, they’re never outspoken, they don’t tell jokes. And here it was the complete opposite! It was, in some ways, very intimidating. But I gravitated towards that because it felt so comfortable.

It was this weird thing. There’s that expression, “You’re a banana,” where you’re yellow on the outside and white in the inside, and I was exactly that because even though I tried to fit in with my Asian heritage, I really didn’t because I still felt like I was an American. I was Caucasian, even though I didn’t look like that.

It was an interesting period for me because there was a part of me that was really responding to a huge part of my life that I’d been missing, but there was another part that I grew up with, where I felt like if I had to choose between two rooms -- a room full of Caucasians and a room full of Asians -- I would always go toward the Caucasians, because that’s what I grew up with and that’s what I felt that I was. It was this weird thing where I had to reassess my life and re-fit in, in some ways.

The great thing is that I had a lot of friends in college because it was a fresh start. I could completely forget my past. College is a great opportunity to reinvent yourself because no one knows your history. For me, it was a great way to assimilate both of those cultures.

StarWars.com: When I create Star Wars recipes, a lot of them tend to lean toward Asian ingredients and cooking methods, not even intentionally. It just kind of comes out that way because it’s who I am and the kind of food I grew up with and lean towards. To me, the Star Wars universe is naturally vast and diverse, and it lends itself to a variety of cultural influences. What cultural experience plays into your work? Is there any intentionality in it or does it come naturally?

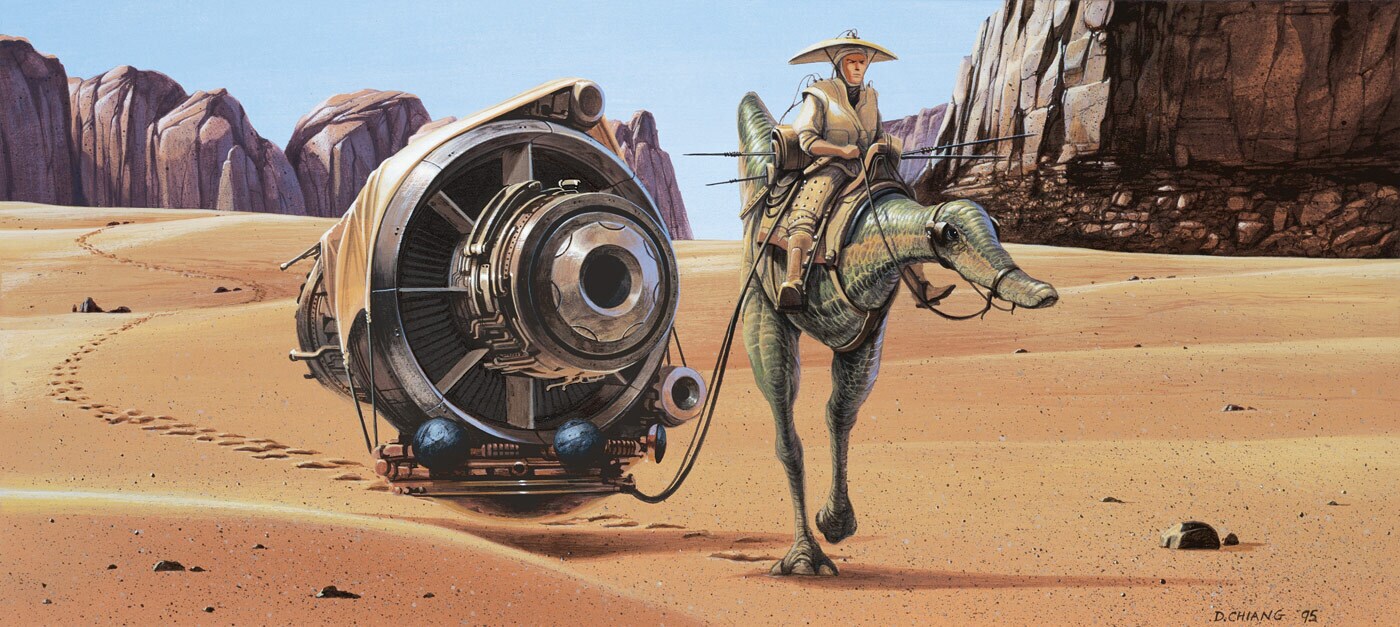

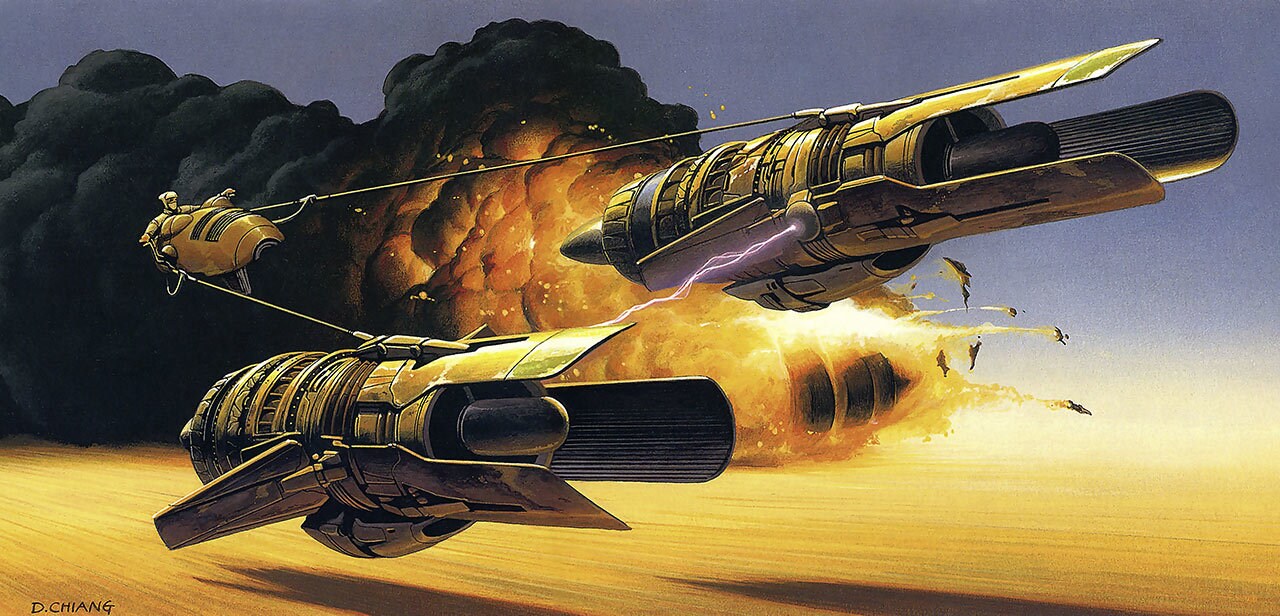

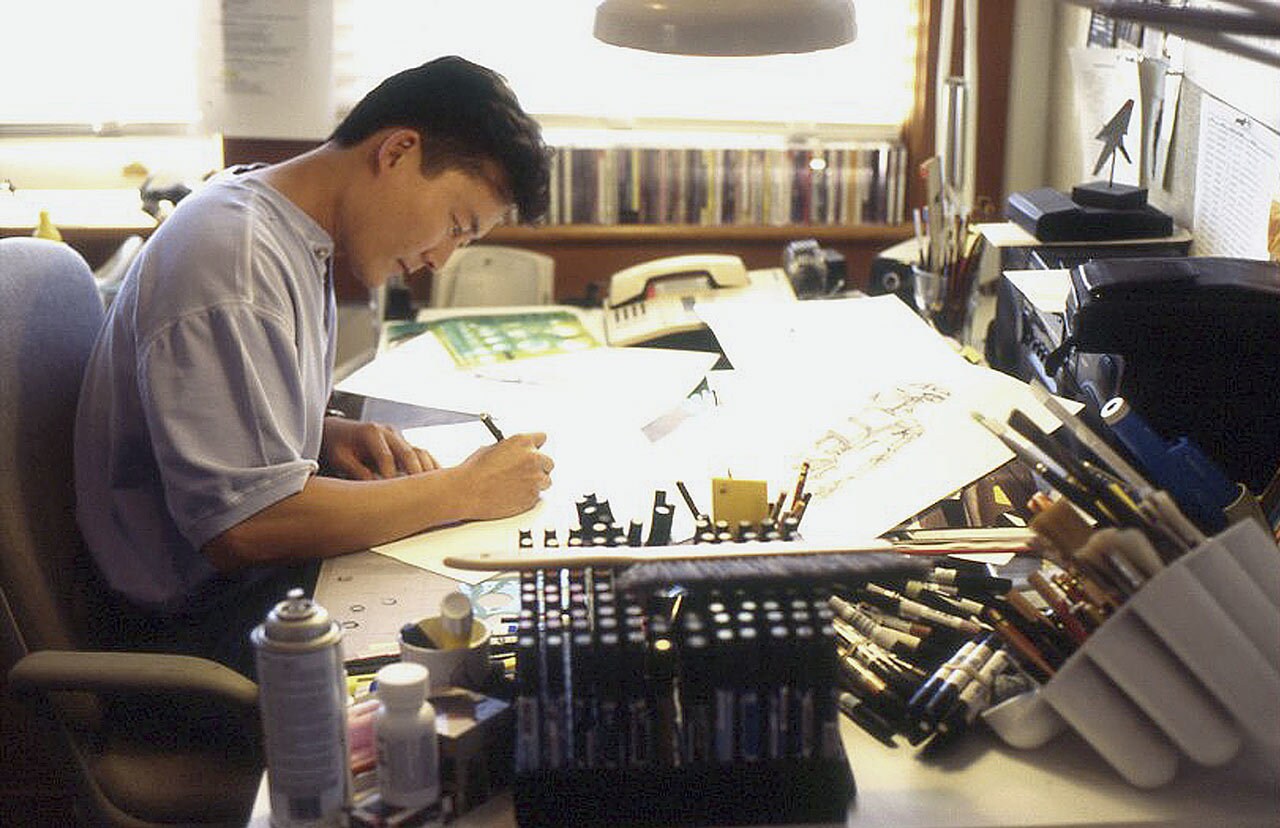

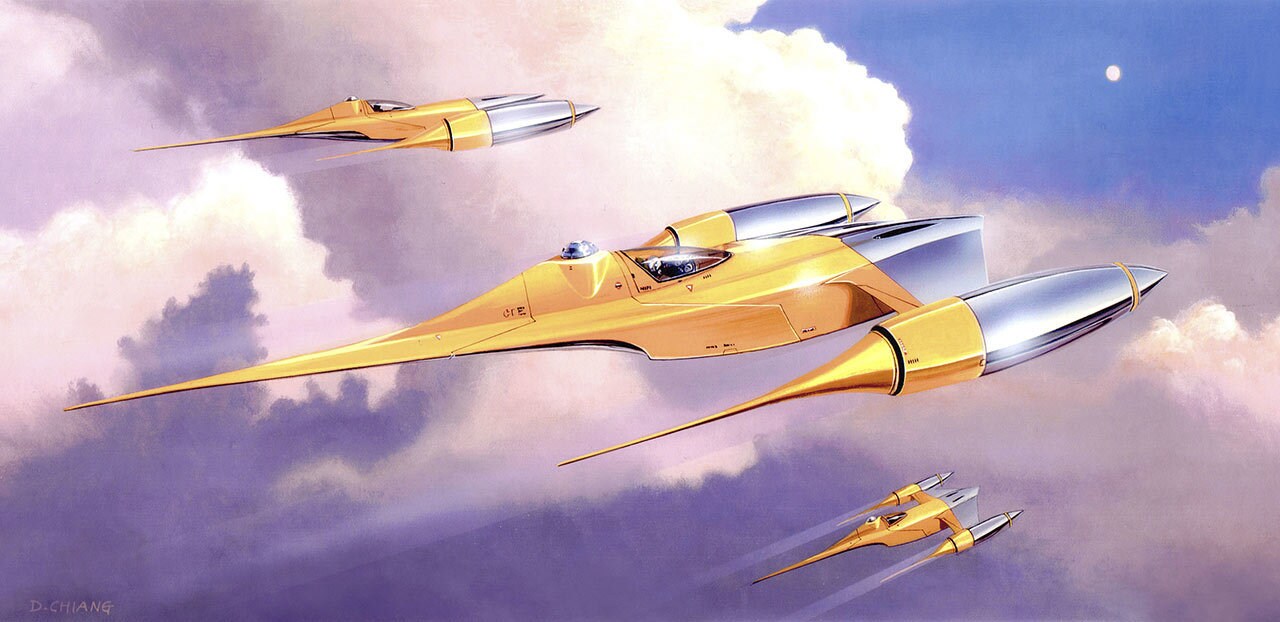

Doug Chiang: A lot of both, actually. I remember when I first started working on Star Wars with George Lucas in 1995, one of the biggest lessons that I learned from him was to study history, study other cultures, to design an alternate future. I didn’t expect that. At that time, my only experience with Star Wars was from watching the original trilogy and looking at the Art of books in terms of design aesthetics. When I finally started to work with George, my first intention was to repeat exactly that, and he was the one who said, “No, we’re going to try something new. Let’s look into different cultures. Let’s study history and study other cultures to come up with exotic designs.” It was such an eye-opener, because he really encouraged myself and the other artists to look at Japanese culture and Chinese culture for design motifs that we could incorporate.

When I heard that from George -- [to] do more of that research, really go in and look into different cultures, obscure cultures, whether it’s costuming or type of weaponry or form language, and bring that into the Star Wars universe [it was eye-opening]. What happens when you design that way, you actually are imbuing a lot of that cultural heritage into the Star Wars designs. It makes it more grounded. That was one way that I started to lean into that more specifically.

Now, with the Obi-Wan [Kenobi] series, working with [Deborah Chow], we both lean into that quite heavily.

StarWars.com: Mentioning that you worked with Deborah Chow, how does it feel working with another Asian person on a project, rather than, sometimes, being the only one? When you work with someone who comes from the same background, you have that familiarity. Has that helped you?

Doug Chiang: Oh, immensely. We have a shorthand. There are certain cultural things that we can understand right away, and culturally specific things design-wise. Like, “Oh, maybe we shouldn’t do this, but this?” Things that, intuitively, we pick up. It’s been an absolute joy working with Deb because she gets it. She’s very smart and knows what she wants. I really enjoy that collaboration because now, I feel like, for the Obi-Wan series especially, we have an opportunity to bring a richness to it that hasn’t been explored. And I’m working with Chung-hoon [Chung], our director of photography, he’s brilliant. He has a wonderful eye.

What I find fascinating is that on the Obi-Wan series there are easily six department heads who are of Asian American heritage. [I’ve] never experienced that before. Normally I am the only Asian in the room and it is a little bit awkward. I do have to check myself, if we’re doing a design, “Is that culturally appropriate? Can we do that?” And now we all kind of do that. We all live in that world, so we automatically know what can work and what cannot work.

StarWars.com: The “model minority” is an inaccurate myth that is sometimes thrust upon us. Sometimes you feel like you take it on all on your own. I even tell people that I’m not The Lorax, I don’t speak for all Asians, but there are times, especially in a work or social situation where you have to be the one to speak up because you’re the only one. Can you talk a little bit about the model-minority myth and your views on that?

Doug Chiang: I first heard about that when I was at UCLA. At that time, I really had no clue what that meant. When I was at UCLA, people started to mention that, because we were still the minority in many ways and treated differently.

Growing up in an Asian family, I rarely ever asked for things. I always felt that you shouldn’t ask for things, that you should earn it. When it’s given to you, then definitely you’ve earned it.

It was a hard thing, because it made me more quiet in the sense that I wasn’t out there selling myself. Throughout my whole career, it’s been a pattern and a struggle, where I feel that it’s more important to do it than to say it. For the people who profess that they can do stuff, I usually ignore them. I just want to see the results.

That’s been my pattern. You don’t ask for things. You just prove it, and they’ll come to you. It’s a hard thing because after UCLA I realized the reality of the world is not like that. You will be overlooked. You will do all the hard work and someone else will get the credit. It’s a hard struggle [that] even today I have a hard time expressing myself in that way.

For the longest time, within the Lucasfilm family, I was one of the few Asian American males in the company. I remember way back, years ago, I was in this meeting to talk about diversity, and I was the only Asian in the room. It was all Caucasians. I remember we were having this conversation and it dawned on me. I looked around the room and I go, “Don’t I count? Should I say something?” Because they were talking as if I was invisible. It was the strangest thing. “Hello, you’re talking about diversity in the company, and I’m right here. Yet you’re not allowing me to participate in this thing.”

It was the strangest experience that I had, where it made me realize I have to speak up if I can. It’s still very alien to me. It’s not my style. I’d rather be the hard worker behind the scenes and get the job done. The downside for my career is that it takes years and years for that to be recognized. [Laughs] But it’s worked out quite well.

It is challenging. I always wonder, if I didn’t have that mindset -- if I was a personality where you’re out there selling yourself all the time -- would it be different? To be honest, that’s not me. I like to prove my worth by what I do and not by what I say. That means more to me because at the end of the day, it feels more authentic when the rewards come.

I’ll give you an example. About 15 years ago, I had an opportunity to form a company with Robert Zemeckis, called ImageMovers Digital, with Disney. At that time, we had been working on several films and I was production designer on several films. Disney approached him to form a company. I thought, “Okay, I’ll be invited and I’ll be part of his team.” I didn’t realize until later when he asked me that he wanted me to head up the company, and to lead the company with him and his producers Steve Starkey and Jack Rapke.

It was a defining moment because, at that time, I didn’t think that I was worthy of that position. I didn’t think that they had looked at me in that light at all. Yet, when it happened -- that they actually put me in charge of forming the company, staffing it up, and put the company up in Marin County near my home -- it was such an affirmation of my self-worth. It felt like the whole 25 years of hard work was paying off. It felt very genuine and earned.

I remember that specifically because it was like, “Okay, all that paid off.” I liked that feeling because then it did feel heartfelt and earned and deserved. It’s one of those things where I’ve seen so many in the film industry where it is all about the gift of gab, about selling yourself. I’ve seen so many people do it. I’ve seen so many careers skyrocket, but then they actually can’t sustain it because there’s nothing underneath. I remember early on I didn’t want to be like that. That was not me. Even if it took years for my role to be recognized and respected, I’m comfortable with that.

StarWars.com: I think it’s that authenticity and it’s more of something that you’ve put on yourself than other people would see. I think, again, that’s sort of a very stereotypical, culturally Asian thing. “I don’t want to speak up and tell everyone I’m amazing, even though I think I’m amazing, I want you to tell me that I’m amazing.” [Laughter]

Doug Chiang: I suffer tremendously from the impostor syndrome. It’s a classic Asian thing. I’m overcoming it but it is real. That’s why it was really encouraging for me when I went to UCLA and I saw other Asians who were completely self-confident and boisterous. Like, “Hey! Look at me! I’m all about me!” I was kind of like, “Wow! Okay!”

StarWars.com: 2020 into 2021 has brought focus to the Black Lives Matter movement and the escalation of Asian American hate crimes. Watching from the couch was overwhelming and all-consuming for me, I think, because we were home. We had nowhere to go to refocus our energy. How did that affect you and your family?

Doug Chiang: Tremendously. It was heartbreaking to see that on the news and to see it come into reality in such a stark and frightening way. It was interesting in the sense that, when I grew up in Michigan, that was completely the norm for me. I never felt comfortable walking out because I just knew that I was going to be picked on and it was always dangerous for Asian Americans in Michigan. Not that the community was unsafe, I just never felt very safe.

So when I saw that happening and playing out in real time worldwide, it brought all those memories back. It made me realize the world can be a terrible place sometimes. For us, we did talk about quite a bit, because my wife is Caucasian. So we’re a mixed family. We just wanted our kids to be aware of all that.

They’re isolated in some ways, and culturally they haven’t really experienced the rest of the U.S. There are pockets that I’m sure they might get a lot of hassle because they’re half Asian. So we wanted to protect them from that in some ways and give them the information that this is a reality. The bubble that we’re living in is not worldwide and we have to be careful.

For me, specifically, it was always on my mind because of the way I grew up. I just knew that danger was always around the corner. Not to say that I was always going to be mugged or anything like that, but it was always conscious in my mind. So when I went out, I was always alert. It’s kind of sad to say that, but that was the way I grew up.

StarWars.com: What do you see for the future of the Asian American community coming off this year of the pandemic and the hate crimes? What would be next?

Doug Chiang: That’s a hard question. I would hope that we aren’t treated any differently because of our Asian heritage, because I feel that it’s all based on the individual and the personalities and that things have to be earned. There is a strength in Asian culture that I would love to embrace more so. It’s really about educating other people about what that is.

Definitely, in Hollywood today, Asian Americans are underrepresented. That’s hard for me because it feels like we’re always behind the scenes. It plays into that classic model minority [stereotype]. “They’ll be fine. We don’t have to pay attention to them.”

Yet I feel the burden of trying to live up to that. It can be unbearable sometimes, because we’re really trying to do that. There is still a classic stereotype, which breaks my heart, because I had that -- that Asian Americans are kind of subservient. They’re kind of not leading characters [or] leading actors. They’re just second-class citizens. I remember growing up in Michigan, I had always felt that.

Now I realize, moving forward, I hope that flips. I hope the rest of the country switches that. At the end of the day, it is about the individual. There are different characters in all cultures. I hope that they can start to appreciate that there are Asian Americans who are worthy of being leaders within this community.

StarWars.com: Especially in Hollywood, when everything is so visual, and it goes out across the whole world and everyone can see it. I think the more people that see Asians in leads and Asians in movies that are doing well would be something that would help. Now, as you said, it’s much easier than before when you didn’t have any.

Doug Chiang: I hope the future becomes more embracing of that, understanding, and more inclusive. I definitely see progression in that in terms of diversity within the company [and] diversity within Disney. I am very optimistic with that.

StarWars.com: You said that you have children. How are you telling them about their heritage? Now that things are the way they are, how are you imbuing your Chinese culture into your own children?

Doug Chiang: I’m telling them that being Chinese American rocks! [Laughter] You’ve got to embrace it and really lean into it! Our youngest daughter is learning Mandarin and she loves it. There’s a lot of those elements where my parents encouraged us to fit in really well. Now I’m encouraging our kids to fit in but also embrace our heritage because it is a substantial part of them, and they should acknowledge that. They have and it’s terrific because I can see that side of us. It becomes a perfect blend of the American dream.

I guess the last note, Jenn, would be one of the strengths that I have being Asian, and it was one of the qualities that I learned from my parents, was that we always work extra hard, no matter what, just because we always felt like we were underdogs. That was something that always stayed with me. I remember in high school and then especially in college, and then even after college, I always felt that I had to work twice as hard as my next peer because otherwise I couldn’t level the playing field.

That’s one of the reasons why I’ve attained the career that I have now, because of all that homework. It was a strength that came from my parents because they were very much like that. They were very studious, and they just worked very hard. It was a quality and a habit that I developed very early on. I think it’s helped make me very successful.

I have to say, when you were asking me about our kids, I see that same quality in them now. I didn’t really push that, because I didn’t want to become that Asian family -- the Tiger Mom or Dad, and really push them hard, because I really wanted them to enjoy it and want it themselves and not have this outside force imposed on them.

They must have picked it up because they see how I work. They naturally gravitate toward it. It was actually refreshing to see that they’re learning that on their own, they’re developing their own habits. Whether it’s sports, whether it’s working out, whether it’s academic, they’re putting it all in. I just love that attitude because that was how I grew up. Nobody had to teach me that; that just felt natural. I’m just glad that that part rubbed off on them. [Laughs]

This discussion has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Jenn Fujikawa is a lifestyle and food writer. Follow her on Twitter at @justjenn and check her Instagram @justjennrecipes and blog justjennrecipes.com for even more Star Wars food photos.

Site tags: #StarWarsBlog, #ThisWeek