The middle chapter of the prequel trilogy, Star Wars: Attack of the Clones, arrived May 16, 2002. To celebrate the movie’s 20th anniversary, StarWars.com presents Clones at 20, a special series of interviews, editorials, and more.

For a century, the technology of filmmaking remained largely the same. Cameras photographed images on physical rolls of film (as did the microphones for soundtracks). Those images and sounds were edited into sequence by physically cutting and rejoining pieces together. The finished reels were then spooled into a projector and screened inside a theater. Year by year, project by project, George Lucas pushed Lucasfilm to change that process.

Lucas was motivated as much by common sense as a boldness to innovate. After years of working in the traditional method, he was convinced that every aspect of filmmaking could be easier, from pre-production and principal photography to post-production and distribution. The Star Wars films, among other Lucasfilm productions, granted opportunities to test and experiment new methods.

By the 1990s, Lucasfilm had helped introduce digital non-linear editing for both picture and sound, computer-graphics visual effects, and digital pre-visualization. As he returned to Star Wars with his new prequel trilogy, George Lucas was committed to making a feature-length film with entirely digital tools, both to free his own creative abilities and to demonstrate that it could be done at the level of an effects-heavy blockbuster. Star Wars: The Phantom Menace (1999) would inch closer to this goal before Star Wars: Attack of the Clones (2002) finally achieved it. Here are four ways that Episode II helped change filmmaking at the dawn of the 21st Century.

1. It employed the first digital cinema camera.

To create a motion-picture without photographic film, Lucasfilm needed a camera equipped with digital sensors that captured and stored imagery on high-definition tape. The resolution of this imagery needed to at least match -- preferably exceed -- the quality of standard 35mm film. The ability to digitally capture, transfer, and edit motion-picture footage would drastically increase the efficiency and flexibility of the filmmaker, something Lucas was eager to do.

Video-based camera systems had been commonplace in broadcast media and other fields for years, but faced skepticism among some feature film cinematographers and directors. Lucasfilm first used Sony’s “digi-beta” cameras to shoot behind-the-scenes material on The Phantom Menace. Select pick-ups from that movie were then captured using one of the company’s digital cameras, and were seamlessly integrated with the rest of the film.

For Attack of the Clones, Lucasfilm convinced Sony to develop cinema cameras that captured digital footage at 24-frames per second, the same as traditional film cameras. This intrepid effort involved engineers from multiple continents, collaborating with Lucasfilm’s staff, including high-definition supervisor Fred Meyers, post-production and technical supervisor Mike Blanchard, and cinematographer David Tattersall.

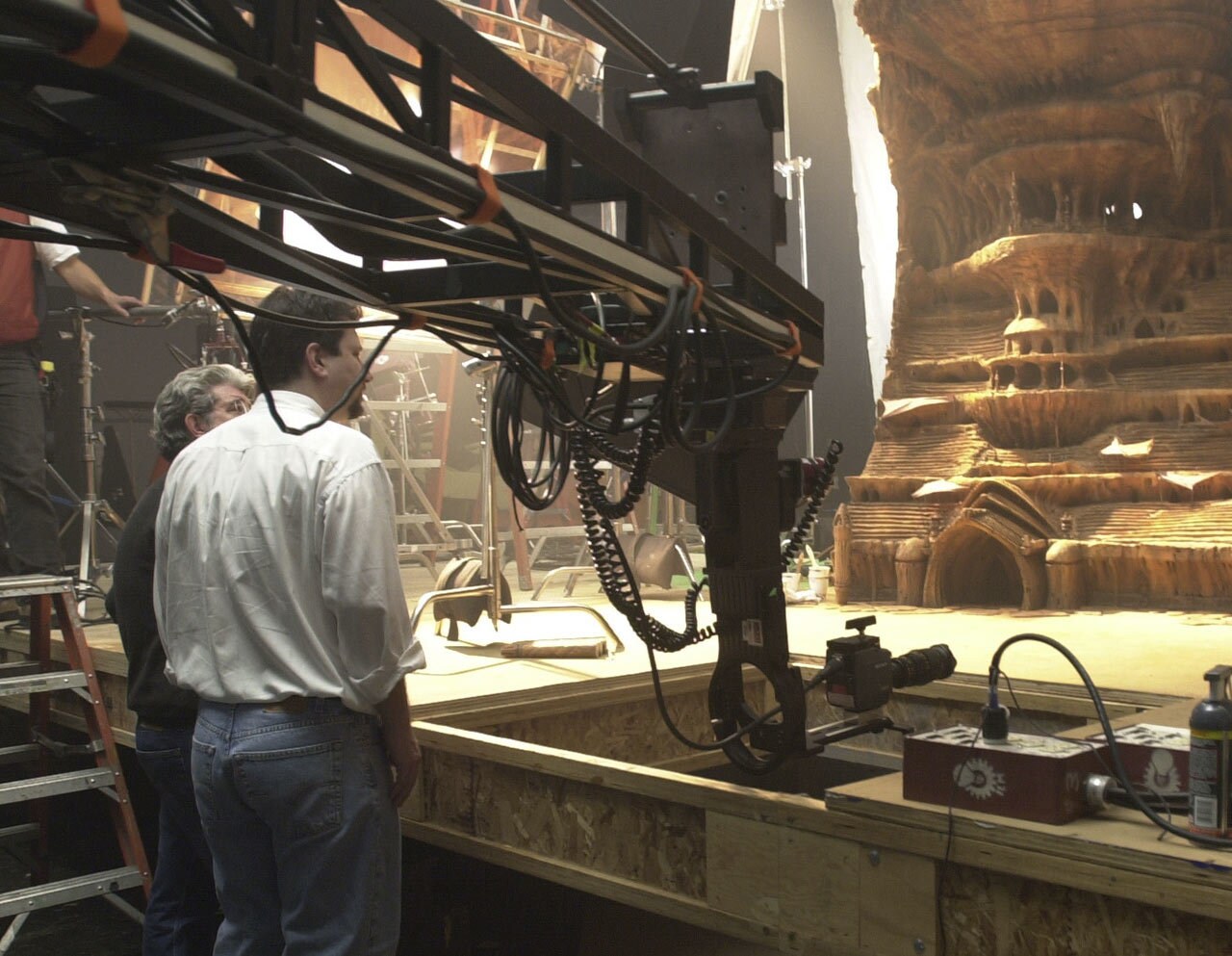

The new cinema cameras were first-of-their-kind prototypes. Lucasfilm had barely a year to finalize their design with Sony, which included custom lenses built by Panavision. The four cameras arrived (serial numbers 00001 to 00004) only days before the commencement of shooting. The crew had to relearn their jobs, and the set was buried in miles of cable, but they worked. Even in the sun-baked deserts of Tunisia, they worked.

2. Cast and crew could view instantaneous results live on set.

Using a digital camera meant that a live feed of the high-definition footage was available to view in the moment from large plasma screen televisions on the set. Whereas in the past, directors hunched over tiny video monitors with black-and-white screens, George Lucas and the crew of Attack of the Clones enjoyed a large, detailed view of their work. This allowed everyone from hair and makeup artists to set dressers to make adjustments in the moment and contribute ideas.

The benefits extended beyond the immediate set as well, as tapes of high-definition footage were copied and transferred to the editorial department where assistant editors could load, input, and begin cutting footage within hours of the cameras rolling. Within the same day, Lucas and team could review the day’s scenes and determine the success of a shot. A typical film production had to wait at least a full day for lab processing of film dailies. No more sleepless nights for the cinematographer, and no more second-guessing about whether to strike a set out of fear that the day’s footage was unusable.

As a Star Wars movie, Attack of the Clones was one of the most expensive independent movies ever made, but these advancements allowed Lucasfilm to run the production as efficiently as possible.

3. It enabled more freedom and flexibility for the visual effects pipeline.

With over 2,000 visual effects shots in Attack of the Clones, much of the pressure rested on Industrial Light & Magic (ILM). It was essential that Lucasfilm’s digitally-captured footage be smoothly imbibed by ILM’s software-based workflow and procedures known as the “pipeline.”

In previous years, much of ILM’s process had already adapted to computer-based tools, from pre-visualization and compositing to character animation and motion-capture. Right alongside major achievements like the creation of a fully-digital Master Yoda and the epic battle that launched the Clone Wars, ILM began using Sony digital cameras to capture its elaborate miniature sets. Decades after ILM’s original crew on Star Wars: A New Hope (1977) used a hand built computer to create a motion-control rig for their traditional film cameras, now both the rig and camera were digitally-operated. (Because of the high-definition range of the cameras, ILM’s miniatures were also visible in greater detail, a fact appreciated by many of the Model Shop crew who masterfully created them.)

Similar to the ability of George Lucas and the production crew during principal photography, the ILM team could view their footage live onset. They also initiated “digital dailies” where high-quality visuals were screened for regular reviews as opposed to the usual work prints of scratch-induced, heavily-used film that sometimes left the artists guessing at details. Again, better quality allowed for greater efficiency and freed the artists to be more creative. In addition, the ILM team would help supervise the digital color timing of the movie in-house, a process usually reserved for third-party vendors at the tail end of post-production.

4. Hard drive to movie screen distribution at a theater near you.

After years of work, Lucasfilm had a digitally-crafted movie in its hands, one that millions waited with anticipation to see. But how to get it to them with all the benefits of this digitally-enhanced quality?

Some theaters would be equipped with new digital projection systems with the ability to display the most authentic version of the film’s imagery and sound. Other theaters, however, continued to use their traditional film projectors. For years, Lucasfilm had gained experience in theatrical film distribution with its implementation of its THX Sound System and Theater Alignment Program. The harsh realities of theatrical presentation were clear enough: the quality of movie prints varied to great degrees from reel to reel and theater to theater, often resulting in a diminished version of the movie the filmmaker had intended the audience to see.

In order to ensure the best possible quality of the required film prints, Lucasfilm devised means of creating reels that surpassed the usual standards for quality. The typical process to create the many prints of a movie involved the duplication of film negatives across two or three generations, each with successive loss in image quality. Lucasfilm instead ran its prints directly from an original negative created with the digital source material. The result was a consistently better presentation across the many thousands of screens where the movie premiered.

Just three years earlier, The Phantom Menace had screened digitally in only four theaters nationwide as little more than an experiment in exhibition. Although Lucasfilm had pulled off quite a feat in raising that number considerably for Attack of the Clones, the majority of venues would still only present the newest Star Wars movie with traditional film projection. Much of the movie industry was still raising its collective eyebrow at digital cinema, but in the ensuing two decades, we’ve seen those numbers turn over as more and more filmmakers and exhibitors learn the benefits of a digital system.

A new way of doing the same thing

All of the digital innovations pioneered at Lucasfilm were tools. Not ends in themselves, each was secondary to the central task of telling a story. Lucasfilm’s contributions to the evolving craft of filmmaking were not intended to change the fabric of storytelling, but rather to improve the capabilities of the medium. While enhancements abounded during production of Attack of the Clones, the process of telling the story remained very much the same, only with more tools at the disposal of those telling it.

“I’m just somebody who’s trying to tell stories,” George Lucas told American Cinematographer in 2002, “and in order to tell the kinds of stories I’ve wanted to tell I’ve had to push the medium. But all the directors and cameramen I know push the medium. They’re always trying new things, trying to get a different look or push something a little further by using a new trick or a new technology. That’s the nature of the business. Everybody does it, but I get more attention for it.”