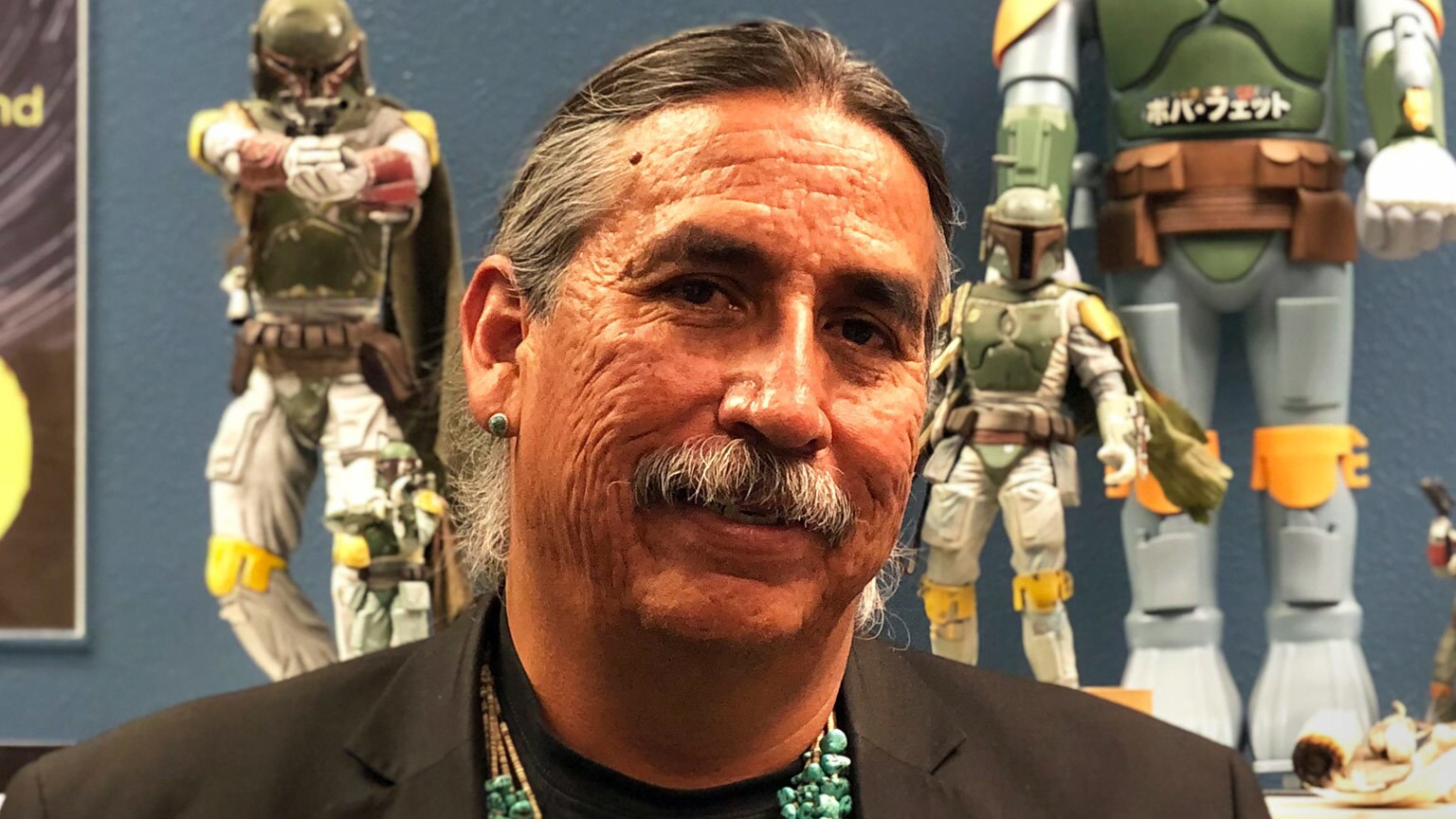

In late October, clone-Fetts Dickey Beer and Bespin Boba rendezvoused in the high-desert at the Buffalo Thunder Resort and Casino for Jim Burleson’s Santa Fe Comic Con. This particular bounty-hunter reunion was beneath the expansive Sangre de Christo mountain range -- sacred to the Navajo people -- where J. Robert Oppenheimer fashioned the world’s first atomic explosion. Joining us was another metaphorical “destroyer of worlds,” film’s legendary visual effects director and soft-spoken Jedi Bruce Logan. During our two Star Wars panels, Bruce electrified attendees with his own buffalo thunder -- his accounts of detonating the Death Star, Alderaan, and an assortment of TIEs and X-Wing fighters during the making of Star Wars: A New Hope. Logan’s 50 years in film have produced truly epic cinematic images.

Born a Londoner, Bruce Logan began his hero’s journey by making animated films at 14. He learned his craft from his father, Campbell Logan, a BBC classical drama director. “My father told me that every frame of a film should be a perfect picture,” says Logan. “He told me how to do my first special effects -- a split screen. He is responsible for all my knowledge of film history and for introducing me to the films of all the great directors of the day, including Stanley Kubrick.”

In the sixties, Bruce was working as a visual effects artist. Kubrick’s special photographic effects supervisor on 2001: A Space Odyssey, Douglas Trumbull, hired him onto the picture. In the following two years, Logan worked on the film as an animation artist, cameraman, and shot designer. “2001 was my film school. I was hired as an animation artist, but when they found out I could also shoot animation, I became doubly useful. I shot and designed most of the readouts. I designed some and shot much of the Jupiter sequence. I shot the opening title sequence for the movie, and then shot it seven more times for all the foreign versions,” says Logan. “Stanley didn't want any country to have a dupe-negative -- especially at the beginning of the movie.”

After 2001, Trumbull brought him along to work on Michelangelo Antonioni's Zabriskie Point. “But our footage was never used,” he says, “until it reappeared in the opening title sequence of Blade Runner.”

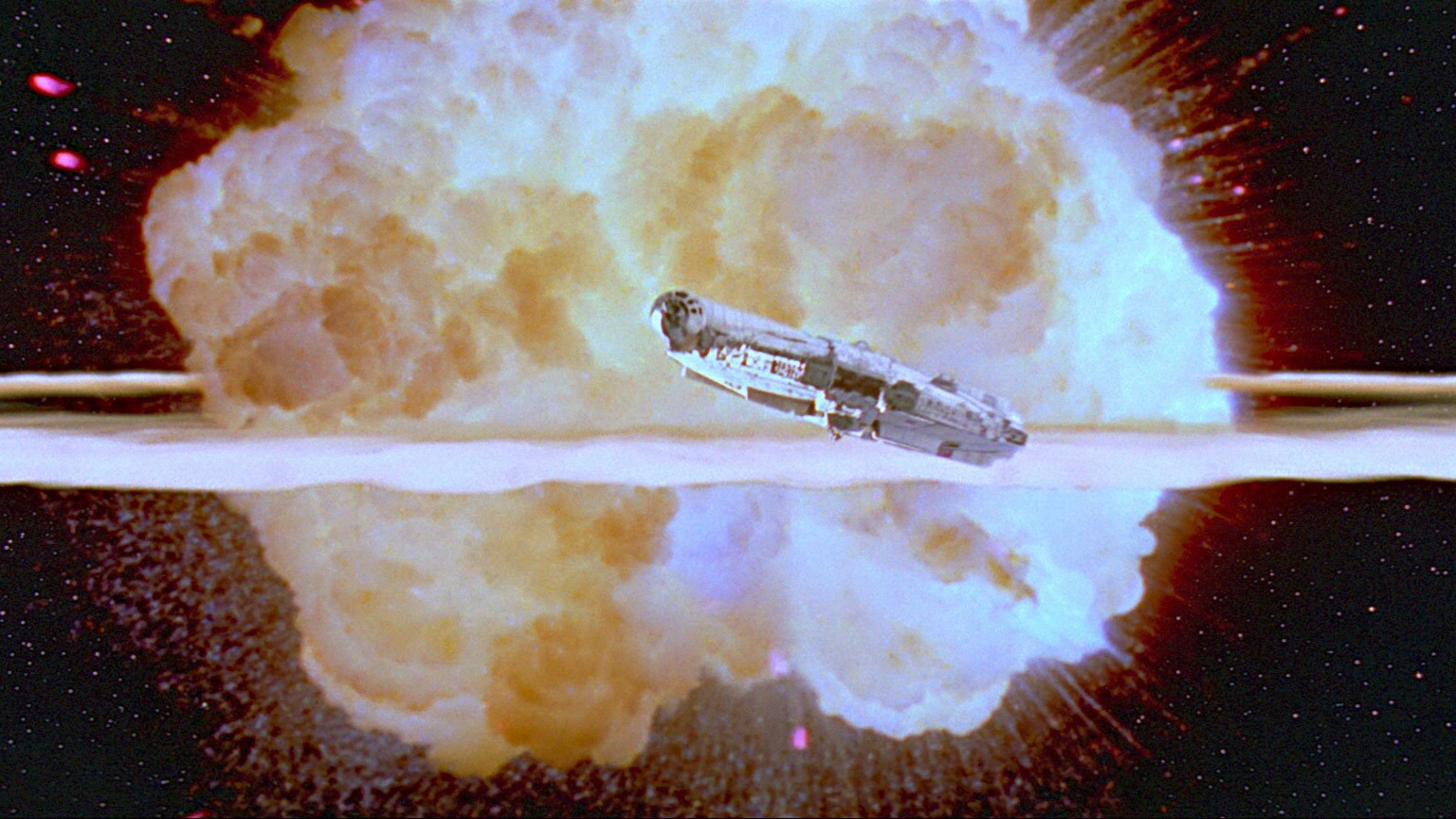

In the early seventies, when George Lucas started putting together his team for Star Wars, he interviewed Logan to be his effects supervisor. “My career at the time was moving forward as a feature DP [director of photography], and I wanted to stay focused on that. But when George returned from England, he was frustrated with his perceived lack of progress for shooting the motion-control spaceships.” Lucas wanted him to shoot puppeteers in black velvet suites flying spaceships on black rods through the frame in high speed. “This rather novel idea didn't work out,” says Logan, “but my unit then went on to do the miniature explosions.”

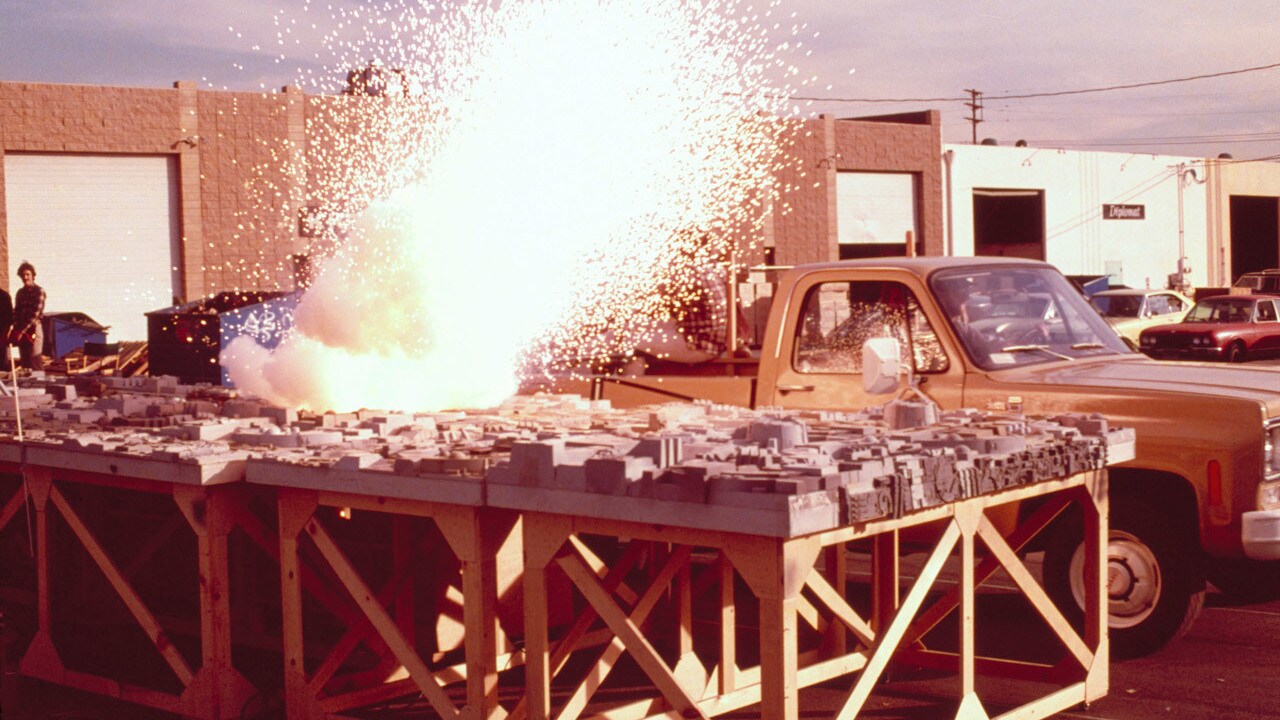

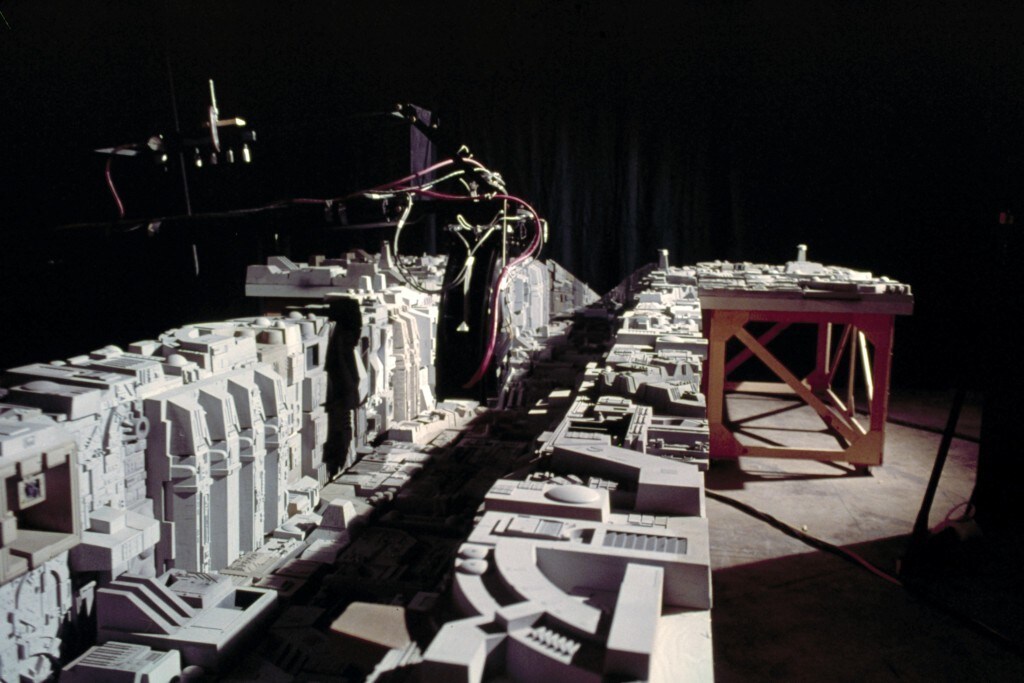

His credit was second unit photography of the miniature and optical effects unit. Logan worked as DP and led the unit that produced the majority of the large featured/miniature explosions. “Joe Viskocil [the late special effects artist] did the miniature pyro work and made all the multi-layered bombs which were rigged overhead and shot with high-speed cameras.”

Bruce and his crew of eight began work in September 1976. “Our unit started out at the Berendo stage, but we soon found out that the bigger the explosions looked, the better. So we soon outgrew the ceiling height and moved to Stage 5 at the Producers’ Studio across from Paramount and shot against a forty-by-forty bluescreen lit with eight blue carbon arcs. We shot 35mm spherical at about 120 FPS [frames per second] and VistaVision high-speed at 110 FPS.” Logan’s team used squibs to detonate silt, magnesium, and gasoline-based explosives. “We let off massive explosions with very little safety equipment and no fireman. I remember wiping burning napalm off my arms after a particularly large explosion.”

Logan’s team had all their creative meetings with Lucas at the Van Nuys facility. “Richard Edlund [the first cameraman for the miniature and optical effects unit] did not work directly with our unit but asked for the particular formats that our work be shot in.” In the winter and early spring of 1977, the unit began blowing up models. “I was not involved in the trench shoot per se,” he says, “other than producing explosive elements and the ship which were blown up and optically inserted into the trench sequence.” Logan adds that he used the Van Nuys machine shop extensively to make parts for his race-car. He is a champion race-car driver and a licensed pilot.

Post-Star Wars, Logan continued to ascend in his film career, working as a director of photography or DP for special effects on over a dozen films. They include I Never Promised You a Rose Garden, Airplane, The Incredible Shrinking Woman, Batman Forever, Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas, in which he also served as a second unit director, and film’s first cyberspace thriller, Tron. In 1986, he directed the prison action film Vendetta. Over the last 20 years, he has directed and shot music videos (Prince, Madonna, Rod Stewart, Aerosmith, Glenn Frey, The Go-Gos, Karyn White, Tevin Campbell, Hank Williams, Jr., and Michael Cooper), a PBS Great Performances episode, and a host of commercials all featuring a distinctive Logan touch, as evidenced by this most visually kinetic montage on his website.

The supremely innovative Logan has maintained his relationship with Trumbull. In 2009, he helped develop a virtual set process with Trumbull’s Entertainment Design Workshop. Says Logan, “Doug built a new camera system called "Zero-G" which was basically a handheld camera which encoded all its movements into a computer and drove a Virtual Set. In its final incarnation we were able to shoot puppets against bluescreen and show a full rez [resolution] final composite of the puppets inside the virtual set in real-time.”

Logan now has ascended to the point where he has his own production company, Seventh Ray Entertainment, that puts his accumulated experience and many facets together. Recently he has been prepping to direct two films, Cowgirls, a western shot in New Mexico, and a cop thriller, Painted Dolls. Providing an insight into the intentionally Theosophical name of his company, Bruce offers that his mother was “an ardent esotericist.” “I had been introduced into the world of spirituality at a very early age, and so I knew of Joseph Campbell quite a while before he consulted on Star Wars. I was happy to see George and subsequently the mainstream media get a spiritual message out to the masses.”

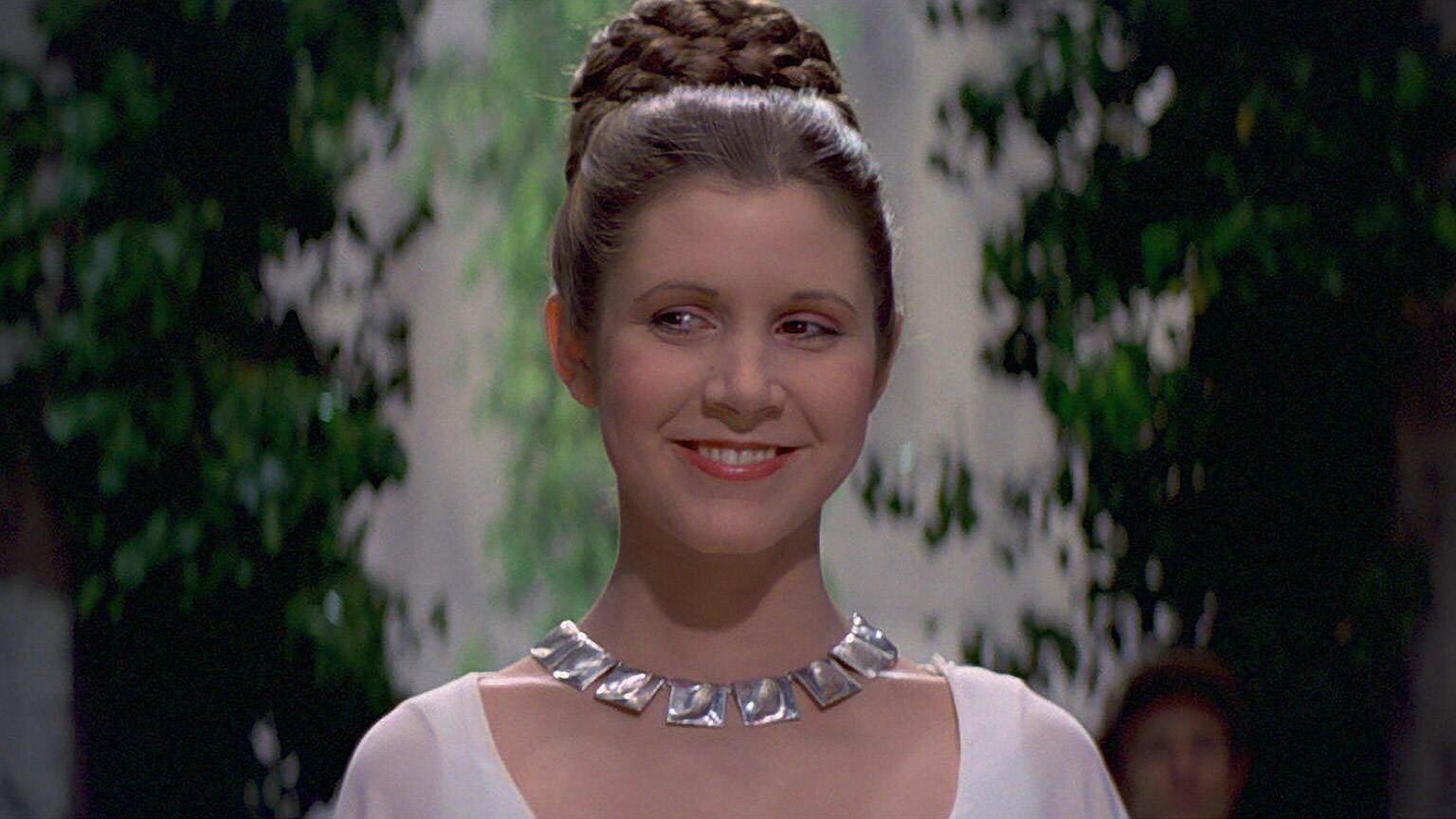

John appeared as Dak, Luke Skywalker’s back-seater in the Battle of Hoth in The Empire Strikes Back. He also appeared in the film substituting for Jeremy Bullloch as Boba Fett on Bespin when he utters his famous line to Darth Vader, “He’s no good to me dead.” Follow him on Twitter @tapcaf.