Kicking off the highly-anticipated prequel trilogy, Star Wars: The Phantom Menace arrived May 19, 1999. To celebrate its 25th anniversary, StarWars.com presents “Phantom at 25,” a special series of interviews, editorials, and more.

Back in 1975, Ben Burtt had been hired as the sound designer for Star Wars: A New Hope (1977), becoming one of the first artists of any discipline to work on George Lucas’ space fantasy. Some two decades later, as Lucas began to lay the groundwork for his new prequel trilogy of Star Wars films, Burtt was recruited once again to join the upstart crew.

“I had been working on some project at the Technical Building at Skywalker Ranch,” Burtt tells StarWars.com, “and I got a call from Jane Bay, George’s executive assistant, and she said, ‘Ben, George wants to talk to you about something. Can you come up right now?’ [laughs] I knew that they always started this way.”

At that early stage, Lucas was still drafting the screenplay for what would become Star Wars: The Phantom Menace (1999). An art department had been established at Skywalker Ranch, and Burtt would start work as not only a sound designer, but a picture editor as well. “It was understood from the beginning that I would do the sound design because that was my official job. But throughout the ‘90s, I had been involved with the Young Indiana Jones series as a picture editor, second unit director, even a writer. I had the chance to wear those hats, and so George knew he could turn to me as someone he knew and was already part of the post-production team. I had been easing into all of these positions on Young Indy.”

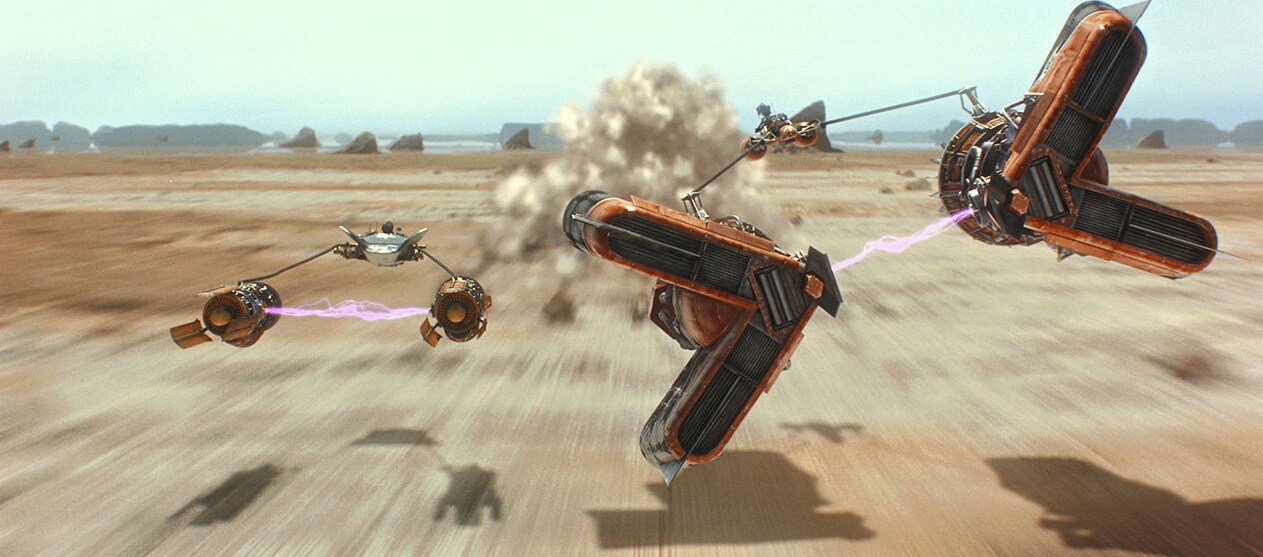

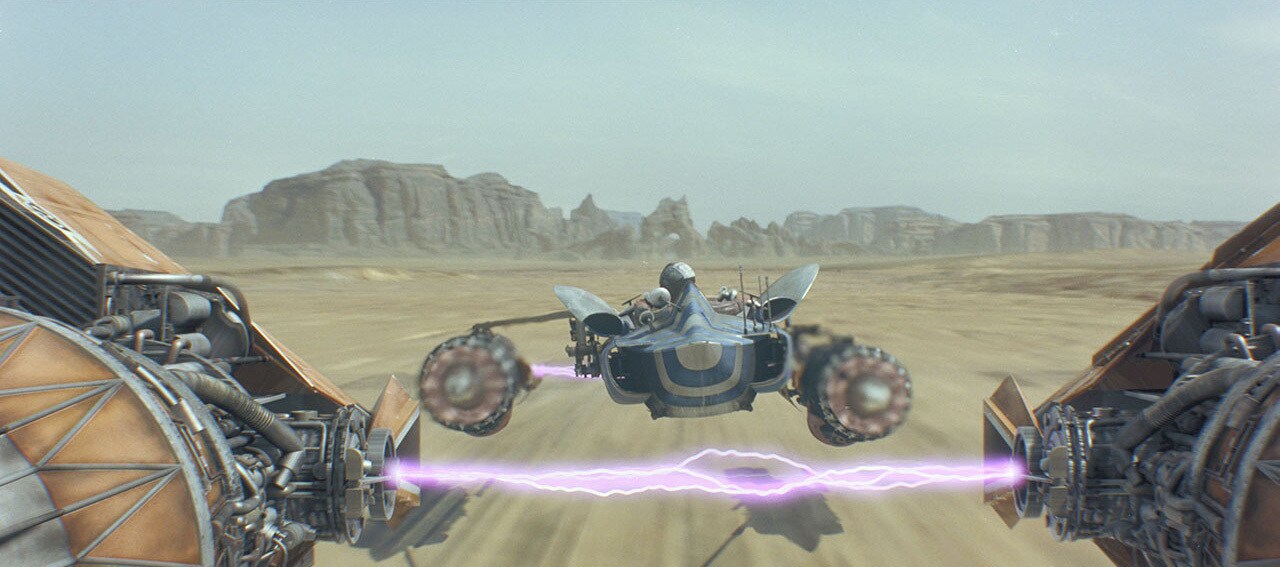

Burtt’s introduction to The Phantom Menace was a lone sequence: the podrace. “George described that he wanted to create this race that, in a sense, was like the chariot race in Ben-Hur [1959], which we both knew well,” he explains. “I knew how to make videomatics, where we started working with images – stock footage of car races, helicopter chases, whatever it might be. We put together all of the different gags and actions from the best chases in movie history.

“I didn’t have a sense of the whole story yet,” Burtt continues. “I was simply working on visuals for the podrace. This was probably six months or more before any filming took place. With his foresight, George always wanted to develop the complex visual effects sequences in a cheap way before you committed ILM [Industrial Light & Magic] to adding their gifts and talents to it at great expense. We had a habit of just shooting home video and borrowing shots from other movies. I was creating sounds for it as well, and we’d sit down to watch and keep developing it.”

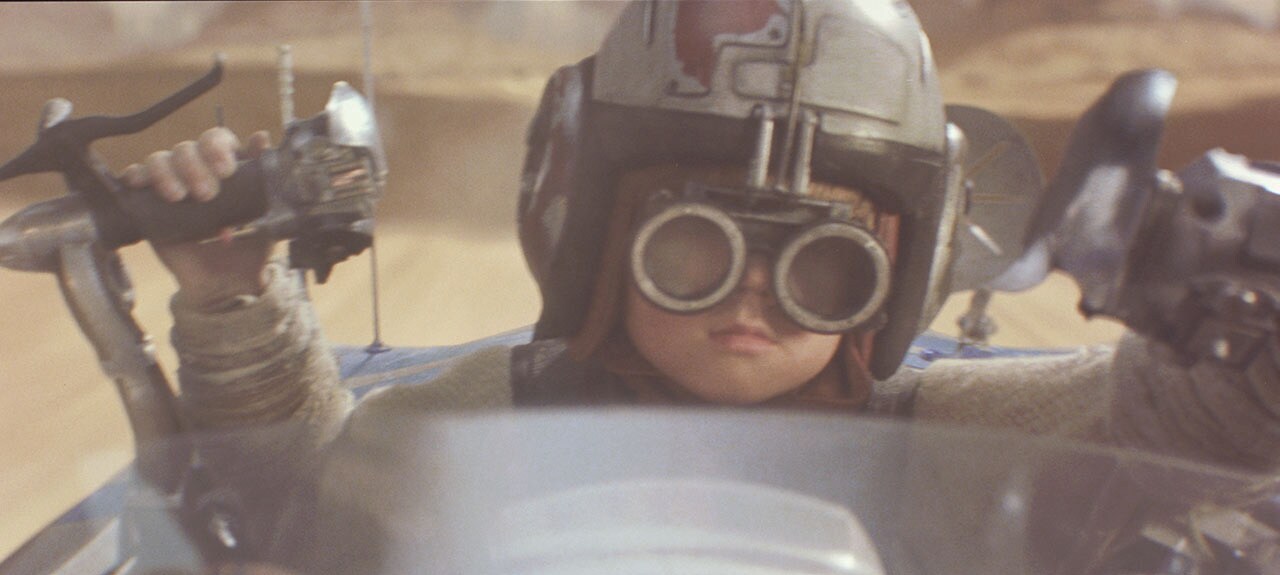

For the earliest versions of the podrace, Burtt mocked up a rear projection screen in his own home and had his 12-year-old son Benny (now a Skywalker Sound employee himself) and his neighborhood friends “fly” in laundry basket cockpits wearing helmets and goggles while desert landscape footage played in the background. Later a green screen was also installed in a basement room in the Technical Building and more elaborate foam core mock-ups of vehicles were constructed.

“The whole idea of developing the videomatics is to determine what the shots are that you really need to make the race,” says Burtt. “What are the angles you need on the characters? Is it a wide shot, a side-view, or a three-quarter view? Do you see two or three pods in the same shot? With video you’re not dealing with a lab or film expense. You can come back the next day and try something else. Remember, George was a pioneer of leaving film behind for digital. The first step was to go to video, which we’d done on Young Indy with the EditDroid, which was developed at Lucasfilm. We could do temporary visual effects in video like dissolves, pans, colors, and re-sizing. It was a work platform where we could quickly mock-up scenes. That was the George Lucas methodology, and today that’s all commonplace. There are companies that create beautiful videomatics with talented artists who can do it all digitally.”

More and more, digital filmmaking tools were being integrated into the overall process. Burtt and fellow editor Paul Martin Smith cut footage using Avid Technology’s Media Composer, a system that utilized Lucasfilm’s former EditDroid software. Together, they had to develop a new workflow to accommodate the many in-progress digital effects elements that were yet to be finalized.

“You’re developing all of the visual effects as you go,” says Burtt, “and there were some important pioneering steps made during The Phantom Menace, in particular the inclusion of Jar Jar Binks. Ahmed [Best] was there on the set for reference and vocal performance, but George had to direct the film in such a way that allowed for the addition of an animated character after the fact. This was a major supporting character who appeared throughout the movie, a first of its kind. Working in the editing room, putting any scene together with Jar Jar, you have a lot on your hands. You’re cutting the scene using Ahmed there, and you’re making all of the pacing and editorial decisions. But then you have to go back and cut a version of the scene with no Ahmed, just with the backgrounds.

“They would do two passes in every scene,” Burtt continues, “one with Ahmed performing and one without him. So for editing, you have two different cuts, one with the Ahmed shots as reference and another with no Jar Jar, just blank backgrounds where ILM can composite the character in. It gets very complicated when one character may step in front of another one or go behind something. Today this is all commonplace. Laying out the visual effects in layers as you’re cutting the film became a responsibility of the editors. Scenes took more time, effort, and care to cut.”

The Avid software even allowed the editors to cut and replace partial segments of a given shot and combine them with others from different shots. Lucas embraced the new capability, multiplying almost exponentially the possible versions of a given scene. Both live-action and digital characters could be rearranged or removed. Different takes could be combined together to form an ideal performance. Burtt would dub the process “re-composing,” and explains that in Lucas’ editing room, nothing was sacred.

“Once he saw where the technology was going, George could begin to fulfill a dream that he’d always had,” Burtt explains. “When he’s in the editing room, he wanted to be able to alter imagery that had been previously captured. He might look at a shot and think, ‘I don’t really want to have this character standing here in the background, so let’s take him out.’ Or, ‘Let’s shrink the whole image and then we’ll expand the set all around them with a matte painting.’ We began doing that with practically every shot. [laughs] The shooting was only providing raw material for yet another assembly of the story.”

Burtt admits that the new process began to alter his thinking as an editor, not to make changes for their own sake, but to continuously improve the drama onscreen. The technology empowered the filmmakers to have more options in the calm setting of the editing room, thus relieving pressure in the hasty atmosphere of a movie set. This workflow had been developed on previous Lucasfilm productions by Lucas and producer Rick McCallum.

“George and Rick took the Young Indiana Jones approach, which is that you shoot the script on schedule,” says Burtt. “If something doesn’t quite work, you do the best you can with it, and move on. Then we put the movie together in a first cut, second cut, third cut. You see where the strengths and weaknesses are, then you go back and do some reshooting. They were always budgeted for reshooting, knowing that there was further need for new or altered material. These weren’t giant reshoots. It was a very specific list of things we wanted to make it a better film.”

From videomatics to principal photography to first assemblies and reshoots, the production stretched over some two-and-a-half years. Because his family had recently adopted a child, Burtt decided not to participate in the main shoot at England’s Leavesden Studios (that job went to another A New Hope alumnus, Roger Christian). Instead, he continued his work at the Ranch, cutting more videomatics, for which he primarily focused on the movie’s action set-pieces like the podrace, battles, and lightsaber duel. He also got down to his traditional work: sound design.

As with the creation of the film’s visuals, digital tools had arrived on the scene at Skywalker Sound. ADR (automated dialogue replacement) recordist and sound editor Matthew Wood led the efforts to establish a computer-based toolset for the crew, for which Burtt gave him the moniker “digital architect.” Burtt himself had begun experimenting with digital sampling programs like ProTools on the Star Wars Special Edition, but The Phantom Menace would be his first full embrace of the workflow.

“I still kept the same basic process,” Burtt explains, “which was going out into the real world and recording organic sounds around us, be they motors, airplanes, or anything. We’d then bring those sounds back in and manipulate them. In the analog world, that meant cutting and splicing and varying speeds on tape recorders. Now we had digital tools that emulated a lot of those techniques. At the beginning of Phantom Menace, I was still doing some work on audio tape, but pretty soon we developed a good method of sampling sounds on a keyboard so I could layout parts of sounds and change their pitch or play them together, as if I was composing music. I could have fire, thunder, or glass crashes laid out on a keyboard and improvise combinations. In that sense, my methodology did change.”

Speed was the key. Burtt’s Star Wars sound library once covered racks of shelving, and editors climbed up and down step ladders, ever on the hunt for the correct roll of audio tape. Now, the entire library was accessible at the click of a mouse. The absence of the traditional hand labor freed up time for creative experimentation. Just as importantly, generational loss when copying sounds was no longer a factor. In one of the earlier analog films, any given sound might have been copied some ten times between different stages of the workflow, each step reducing the overall quality. Digital audio maintained consistent fidelity.

As was typical, Burtt got to work crafting everything from creature roars and atmospheric sounds to alien languages and vehicle effects. The podrace, in particular, would be an extended opportunity for Skywalker Sound to craft an elaborate mix of tracks. It was reminiscent, as Burtt recalls, of the speeder bike chase in Star Wars: Return of the Jedi (1983), where sound effects took center stage, with little dialogue or music. “That was the first time we had a sustained action sequence with sound effects only,” Burtt recalls. “It really only came out that way because the scene wasn’t done when Johnny Williams composed his music. That scene came in very late, and we actually spliced the mix of the scene into the masters of the movie after it had been done. I was very proud of it.”

As with the visuals for the sequence, the podrace’s soundtrack began with a study of movie history. Having studied films with vehicle racing or chase sequences, Burtt understood that often in these types of set-pieces, sound was the primary element. “You want the audience to have the point of view of the racers themselves, surrounded by the roar of the engine,” he explains. “You don’t need music to tell you that they’re going fast or they’re in danger. If it’s well-designed visually and there’s plenty of interesting sound, you can accomplish that sensation with the sound effects by themselves.”

The James Bond entry On Her Majesty’s Secret Service (1969) was a particular stand-out for Burtt, with its climactic bobsled run. “It’s terrific the way it’s cut, and for the most part, it’s only done with sound effects,” he notes. “There’s some music towards the end to add to the climactic moment. I always admired the Bond films in general with their method for ending a movie when they’ll have a finale sequence with A and B portions. The A portion will be only sound effects and the B portion will have music for an additional kick. I love how that bobsled run works because they did so many variations of sound in every cut. The texture changes. There are lots of interesting crashes, hits, and punches. Then they’ll drop back to a farther angle and you’ll hear the sleds going around corners. There are a few sequences in movie history that I admire in that way.”

“So when you get to the podrace, you’re dealing with all of these tonalities,” Burtt continues. “You create a distinctive sound for each podracer so you have a sense of differentiation between them, some that are high, others low. Sebulba had his pulsing engines like a big heartbeat. Another was just an electric toothbrush motor. Anakin’s was a blend of a lot of high-speed racecars. It’s a hodge-podge of high-energy vehicle sounds that the audience knows from their own experience that these things represent power and danger. If you place them in, and disguise them just a little bit so you don’t hear a dragster or a P-51 Mustang, then you capitalize on the emotions those sounds carry with them, because people have heard them in real life. That process goes back to the first Star Wars movie where we built a lot of things with World War II airplanes and jets.”

What began as a nearly 30-minute, 25-lap epic in the videomatic phase, was carefully refined down to a three-lap nail-biter that rivals A New Hope’s trench run in energy and suspense. Lucas and his crew withheld any musical score until the final lap of the race as Anakin Skywalker closes in on his opponent and the ultimate chance of freedom.

“Filmmakers often miss opportunities to use sound in this way,” says Burtt. “I understand the power of music, but there can be a lot of insecurity in terms of what filmmakers think is needed to have the biggest impact. It’s easier to have music run all the way through something and feel like you’ve done your job. But my feeling is that the power of music is so strong that you want to use it carefully. On the other hand, I’ve run some of the sequences in the films without their music and you’re missing something. It’s all about balance, with the right choices made for the right moment in the context of the whole movie.”

By the release of The Phantom Menace in 1999, Burtt had spent nearly 25 years with Lucasfilm, taking opportunities in new types of roles from project to project. As both sound designer and picture editor on Episode I, Burtt was among George Lucas’ closest collaborators, one of the chief architects of the Lucasfilm style of storytelling.