The actor, educator, and futurist looks back on his collaboration with George Lucas and ILM to create one of cinema’s first all-digital starring characters.

Kicking off the highly-anticipated prequel trilogy, Star Wars: The Phantom Menace arrived May 19, 1999. To celebrate its 25th anniversary, StarWars.com presents “Phantom at 25,” a special series of interviews, editorials, and more.

On the day he screen-tested for Jar Jar Binks, Ahmed Best didn’t expect to meet George Lucas. Arriving at Industrial Light & Magic’s (ILM) facility in San Rafael, California, Best was greeted in the main lobby by statues of Han Solo in carbonite and the Energizer Bunny (for which ILM produced commercials). “Everyone knew it was a visual effects house, but I didn’t know how many things were done there,” he tells StarWars.com. “ILM runs that gamut. You can be the Energizer Bunny or Han Solo and everything in between. I was really excited walking through there and thinking, this is a place of infinite possibilities and creativity.”

Best’s next surprise was the format in which his screen test would be shot. A soundstage that looked more like an average warehouse had been converted into a motion-capture volume, technology that was brand new to filmmaking. “They pull out this LYCRA cat suit and say, ‘Put this on,’” Best recalls. “I was like, ‘What is actually going on in here? What am I going to be doing?’ [laughs] They gave me the cat suit and six-inch platform shoes and a headband. They had all of what we now know as targets on them. They were huge. Targets now are really tiny. At the time they were like golf balls.”

Best observed what he describes as a makeshift camera array throughout the space. Nearby, a table was loaded with massive computers, hard drives, and monitors. He tried to ask the ILM team for information about the character he was going to portray, but received little more than “reptile,” “amphibian,” and “like a frog” from the secretive crew. One animator began to sketch a rough portrait of Jar Jar, and Best was able to derive some inspiration in movement from the character’s long ears and slender neck. Then George Lucas walked in.

“Nobody told me that George was going to be there,” Best explains. “I was like, ‘Stay calm. Really, stay calm.’ George Lucas was my hero, and no one really knew how much of a Star Wars fan I was because I was trying to keep it under wraps…. When he walked in, it was like when you almost pass out and you see a kind of tunnel. [laughs] He was very unassuming and I asked him, ‘What do you want to do?’ He just said, ‘Oh, you know, you’re walking through this space…’ I did a series of walks, and he’d say, ‘A bit longer, more loping.’ Then he said, ‘Okay, do whatever you want.’ So I started doing jumps and turns and a couple backflips. Then George said, ‘Okay, great,’ and he left.”

It was after Lucas’ departure that Best was invited to see what the ILM crew was doing with his recorded movements. “Here were these markers, these dots, which we now know as point clouds,” he says. “Now that’s the parlance when you’re talking about performance capture, but at the time, nobody was doing this. These were infrared cameras that were picking up the targets and the point cloud was created…and you would animate over the point cloud. I saw this series of markers move like me, and I was blown away. That’s when I really wanted to do this. It was everything that I’m about. Not only is it moviemaking and storytelling, but it’s cutting-edge on the technology front. That’s when I was nervous because if I didn’t get it, I’d be really upset. [laughs]”

Star Wars: The Phantom Menace (1999) casting director Robin Gurland had discovered Best among the cast of Stomp, a Broadway show created by British performers Luke Cresswell and Steve McNicholas, which was then doing a stint in San Francisco. Best describes Stomp as “communication through found-object percussion. It’s a musical without words. You communicated the message of the show through drumming,” he continues, “but you were drumming on things that you find on the street like garbage cans, fire extinguishers, or oil drums. Whatever you can find that can make a noise, you would pick up a drumstick and hit it. That show was right up my alley. I grew up playing drums. My mother’s a percussionist, and she was my first drum teacher. Stomp was kind of tailor-made for me, especially with being able to communicate through drumming and movement. I started doing martial arts when I was five or six years old, and that, combined with drumming, was perfect for Stomp.”

By the time they arrived in San Francisco, Best had the lead part in the eight-person show. But on the night Gurland attended, there was an unexpected change. A castmate took ill, and Best’s superior relegated him to the minor role, taking the lead for himself. Indignant, he “proceeded to do a show that I would embarrassingly call a show that was mostly my ego and tremendously loud,” he says with a laugh. “I actually felt kind of bad after that show because Stomp is about how these eight people can be this one unit…. I’m going to chalk it up to being young, but that’s the show that Robin saw, and I got a phone call to audition at Skywalker Ranch. I had no idea what the audition was for, but there were rumors flying around about a new Star Wars movie.”

Star Wars ran deep for Best. Star Wars: A New Hope was his first big screen experience at the age of four. As he recalls it, growing up in the South Bronx of New York City with a love for Star Wars provided distinct inspiration. “It wasn’t so much about buying the toys and the merchandise. I couldn’t afford that, but my mother, who would make clothes for me and my siblings, found Star Wars fabric at the local fabric store. She made pajamas, pillow cases, and curtains because she knew we loved it so much. As a very young person, Star Wars gave me access to creativity and imagination.

“It started with me playing with my brother and sister as we imagined Star Wars with nothing but our own bodies,” Best continues. “We didn’t have the stuff. I didn’t have a toy lightsaber or the Millennium Falcon that you could put together. But my parents’ sofa pillows became the Millennium Falcon. Chopsticks became lightsabers. Star Wars was the thing that really sparked the imagination.”

Years later, as he traveled to Skywalker Ranch for his first audition with Robin Gurland, Best channeled that same imaginative capacity. “She really couldn’t tell me anything,” he explains. “Robin’s office was in the basement of the Main House and…I remember it being extremely narrow. At the time, Jar Jar was imagined to be like a salamander, closer to the ground. That didn’t change until my screen test with George. All Robin knew initially was that I’d be moving close to the ground, and every once in a while, I’d pop up when I was talking to somebody.

“That first audition was that first scene in The Phantom Menace when I meet [Qui-Gon Jinn]…but I was doing it with no context, no script, no idea what was going on,” he continues. “I started moving in this narrow office, and I think what sealed the callback is that I did a backflip in there, and I don’t think she knew that I could do that. So I got a call to come back about three weeks later when I was in Washington, D.C. on tour with Stomp.”

Another month or so after his screen test with Lucas at ILM, Best was offered the role of Jar Jar Binks. He left the Stomp cast and flew to England, where principal photography would be centered at Leavesden Studios. He’d earned the role almost entirely on the strength of his movement and ability to intuit a character’s personality through physical expression. At first, he wasn’t slated to provide Jar Jar’s voice, but soon won the full role through his strength of performance at the initial table read and subsequently onset.

“Jar Jar didn’t really come to life for me until that first scene with the Jedi, running through the forest,” Best notes. “I was walking, I was moving, I was with Liam [Neeson] and Ewan [McGregor]. Those were all of the questions that everybody had. Will this work with other actors? Primarily with the eyeline situation. Is this character believable in the scene and out? I would do the scene and then they’d do the scene without me and they’d shoot what’s called a plate, a complete version but empty. Then there’d be a lighting pass when the ILM folks would come in and register the light. There was a whole bunch of engineering going on at the same time. The software engineers were kind of writing the software as we were going to make sure this would actually work. That was the first day when I was like, ‘Okay, this is a thing.’

“I had a lot of constraints on that day, and I didn’t know how much I could do or say that didn’t involve everybody else,” Best continues. “Everything was a conversation about ‘Is this possible?’ I can’t stress this enough, no one in the world knew what was possible with these characters. It’s so interesting that this is so commonplace now that no one even thinks about this. Can this character walk alongside an actor that is a human being? That was a real question that we had to answer.”

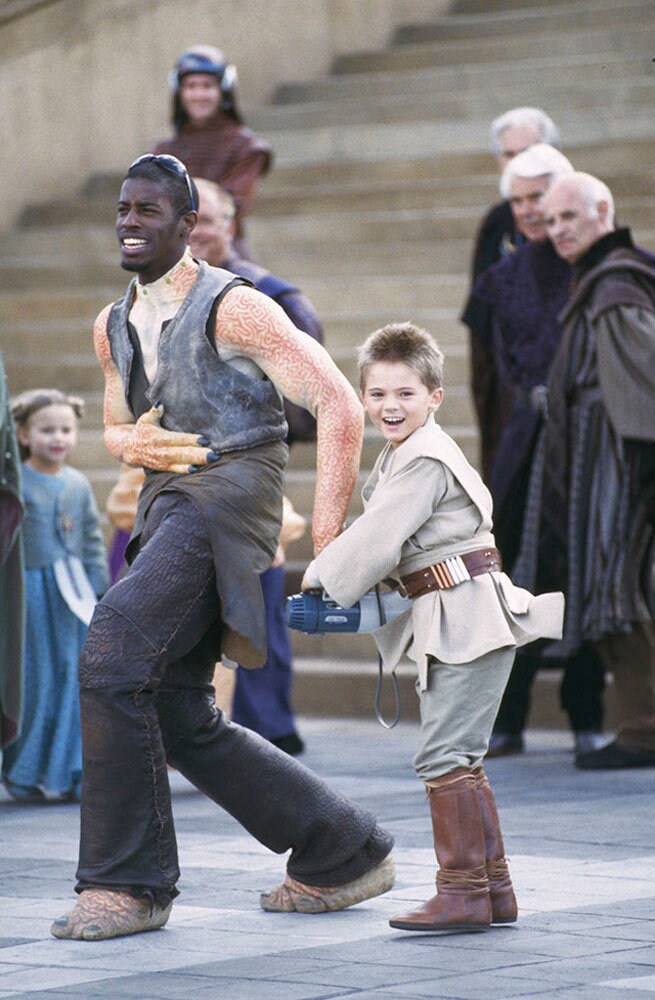

That same day, Best was required to duck to the ground when Jar Jar attempted to evade the blasters of a pursuing droid. At one point, he suggested to Liam Neeson that he had another idea. “I said, ‘Instead of ducking, why don’t I jump straight up and dive onto the ground?’ He started laughing and said, ‘That’s a good idea. Come on.’” Neeson walked him over to Lucas, and encouraged Best to pitch the idea. Lucas agreed, and Best’s movement appeared in the final film. It was an early lesson for Best, who admittedly was among the least experienced actors in the leading cast. This was his first feature film, and even the eight-year-old Jake Lloyd, as Best points out, had already done two.

“The cast was really close during that shoot,” Best explains. “Having played Star Wars with my brother and sister, playing Star Wars with George Lucas was a full circle moment. There was no way I was going to have a bad time.” In many ways, Best’s humor and spiritedness was at the heart of the atmosphere on set, something he cultivated deliberately.

“It’s cool to be the funny guy,” he notes. “Jar Jar was such a comedic character, I could just stay in that space. I had so much experience doing physical comedy that I knew how to make a character like that work and how to keep everybody in that space. It’s very easy for everybody to get a little too serious when it comes to this kind of work. When everyone’s too serious and you’re supposed to be funny, it’s very uncomfortable. I wanted to keep the atmosphere light…just so we could all have fun together.

“Liam was my guy,” Best continues. “Most of the movie is me and Liam together. I always think of The Phantom Menace as a buddy-cop movie between Liam and myself. [laughs] He had just come off of Les Misérables, a very serious Victor Hugo piece, not the musical. He was very happy to have fun and be silly. It was great to just laugh all the time with him and we got really tight because of that. There are some outtakes where we did Star Trek parodies. I would do a Captain Kirk impression, and [Ewan] McGregor would do Scottie because he’s Scottish. There were several times when it was just the three of us waiting, bored, in a Naboo ship, and we’d go into Star Trek bits. Liam would laugh so hard that he’d ask us to stop. We got to play.”

Best not only enjoyed each moment, but continued to learn from them too, treating the experience as the world’s best film school. He “never went home,” as he explains, coming onto set even when he had nothing to shoot on a given day. He’d sit behind George Lucas’ director’s chair and observe. He’d interact with department heads. “I didn’t know if I was ever going to have an opportunity like this again. I wanted to really see how big movies are made, from the micro to the macro.” Best found Lucas’ ability to “solve the daily problems” to be especially meaningful, perhaps most of all during their location shoot in Tunisia when a freak storm nearly sidelined the entire production.

“That was something that no one could’ve planned for,” says Best. “The two weeks we were there was called ‘the devil’s fortnight,’ the hottest two weeks of the year in that part of the world. Everybody thought we were crazy for shooting there. One evening, I’m having dinner with Ewan McGregor, and we hear thunder. Then there’s torrential rain. All of the sets were exposed. The next day, we get to set and everything’s upside down, except for one set, which survived. None of us knew what we were shooting. The schedule they’d spent years on went out the window. I watched George and [producer] Rick McCallum go, ‘We got to do something today,’ and on a dime, they flipped the schedule around, got everybody there, and something scheduled for the end of the shoot was captured that day.”

In an example of what Best describes as “the beauty of being on a film set,” he then marveled at seeing everyone – leading cast, extras, crew – pick up brooms and tools and clean up together. Even the mother of teenaged actor Natalie Portman had stepped in. “[Natalie’s mother] said something that I thought was very profound,” Best recalls. “There was a very interesting culture [in Tunisia], mostly Muslim. Everybody was from everywhere in the cast and crew, and we were all cleaning up, and Natalie’s mom just commented that it was beautiful to see everybody – Jewish, Muslim, English, American – all working together to make sure we can shoot tomorrow. I thought that was very much in the spirit of what Star Wars is supposed to be.

“George always talks about how everybody wants to be a Sith Lord and how the dark side is cool,” Best continues. “But George’s thing was always about how the dark side is easy, the dark side is accessible. The Sith shoot lightning out of their fingers and people ask, ‘How come the Jedi don’t do that?’ It’s not that they can’t do it, but that they learn the control not to do it. Control is hard. Choosing the side of life, light, and harmony is a daily challenge, especially when you have great power. But when you come from this idea of love, then you will forever be on the light side. When love is not the impetus for your action, then that’s when you’re on the dark side. That’s what The Phantom Menace is really about: if you come from this place of love, you can overcome ‘the phantom menace.’”

Jar Jar Binks himself exemplified an element of this compassionate motif. As Best explains, the Gungan takes his newfound companions – the Jedi and Queen Amidala – at face value. He isn’t concerned with their status. Jar Jar has a disarming innocence. He “says what he’s thinking,” as Best notes. Late in the film, Jar Jar asks Amidala if she thinks their two peoples back on Naboo are going to die. “It’s about what is actually going on here. How big is this problem, and how big is this threat? It’s also the moment when he thinks, ‘Maybe I should bring the Gungans into this fight. Maybe we should come together as a planet…. Let’s get out of our bubble underwater and realize that everyone matters.’ That’s how I approached that moment, as well as Jar Jar as a character. Even though he’s clumsy and doesn’t get everything right for the surface world, he’s very much himself and is not intimidated by anyone, except for Boss Nass. [laughs]”

By taking on this pioneering role as the all-digital Jar Jar, Best had what was then an unusual opportunity in filmmaking: the chance to revisit the performance multiple times over some two years of production. He played each scene during principal photography, then again during motion-capture sessions at ILM, and once more during voice recording. It felt akin to a theater experience, as Best explains. “You can be doing a play for a couple of years, and then during one performance you’ll go, ‘Oh that’s what this line means!’ You say it but you don’t get it, and one day it just hits you. So the more I dove into these different aspects of Jar Jar, the deeper I got into it.”

Lucas, Best, and the ILM crew were slowly developing a new way of creating characters for movies, an approach that within years would be adapted by filmmakers all around the world. “There were so many moving parts to Jar Jar,” Best comments. “Often times, I talk about him as a collective character. Although I was the person in the suit and doing the motion-capture, it’s more than me. I like to say that we as a collective are Jar Jar and not me. If it wasn’t for [animation director] Rob Coleman, [visual effects supervisor] John Knoll, the army of visual effects people, George Lucas, and everybody else, there would’ve been no Jar Jar. It didn’t come together until all of those pieces were together on a day.”

Now 25 years later, Best looks back on what “a joy and honor” it was to play Jar Jar. “I’m going to be aging myself, but I was 23 or 24 years old when I started shooting The Phantom Menace. What I always think about is that George had the faith and trust in me as 23-year-old kid from the South Bronx to do this thing.”

Equally youthful was Jar Jar’s audience, an entire generation of children who were introduced to a galaxy far, far away alongside the comedic and lovable Gungan. It was Lucas who’d tell Best that the character’s resonance would endure in the imaginations of these young viewers, something the actor has taken to heart.

“One of the reasons why I think Jar Jar really resonates with young people is because George is always looking towards the future, 20, 30, 50 years down the line,” says Best. “What’s going to happen, and what’s the message we want to give to young people as they grow up? One of the reasons why I call myself a futurist and teach a class called ‘Inventing the Future’ at Stanford where I try to drill down really hard on building optimistic futures is because I saw George doing it in real time. These Star Wars stories really have a strong message that transcends time. We see the kids who are now adults still believing in these movies and showing their own kids, and for a lot of them, their introduction is through Jar Jar, being a child and connecting to this very innocent character. It's inspiring 25 years later that the vision George put into this is still viable. It makes me very excited to continue because we can build this optimistic future.

“Through all of the tumultuous times that we have throughout history, there’s always a way out of dystopia, out of what we’ve come to know as the ‘Empire’ and the ‘dark side,’” Best concludes. “That out is through art. We can ‘art’ our way out of it through story and narrative. We can ‘story’ our way into a future that we want to live in and believe in, that leads us to the light. Darth Vader eventually has that good in him, and it overtakes him so much so that he can no longer hold onto the dark side. That’s the message. Even if you do present in this dark side way, there’s that little bit of light inside that you can feel. That will lead you to love, and in Darth Vader’s case, it was the love of his son, Luke. That’s what I see as the legacy of The Phantom Menace and something I want to help continue with what I do as an artist, educator, and futurist. That’s what we need, and we have to constantly put our faith and trust in our young people, just like George did with me when I was in my ‘20s, and as Jar Jar did with the kids who grew up with The Phantom Menace.”