There was a panel at a relatively small model show Saturday in the community center of my relatively small town, Petaluma, California, population 57,941. That’s not nearly as small as most semi-rural towns in wine country, but for a guy born in Philadelphia it sure is.

There were about 2,000 people who filled the center all day. The display we had at the Rancho Obi-Wan table attracted folks for the length of the show. There were babies in strollers and grizzled granddads whose lifelong hobby has been building exquisite scratch-built and model kits.

But my real point is that the casual 90-minute panel with seven guests and a moderator could have been a million-dollar production and wouldn’t have been one bit better. Because eight truly talented former ILM model makers spun stories, opened windows into their psyches, and actually gave folks some hope that a business many of us have feared was not far from extinction would live on for another day.

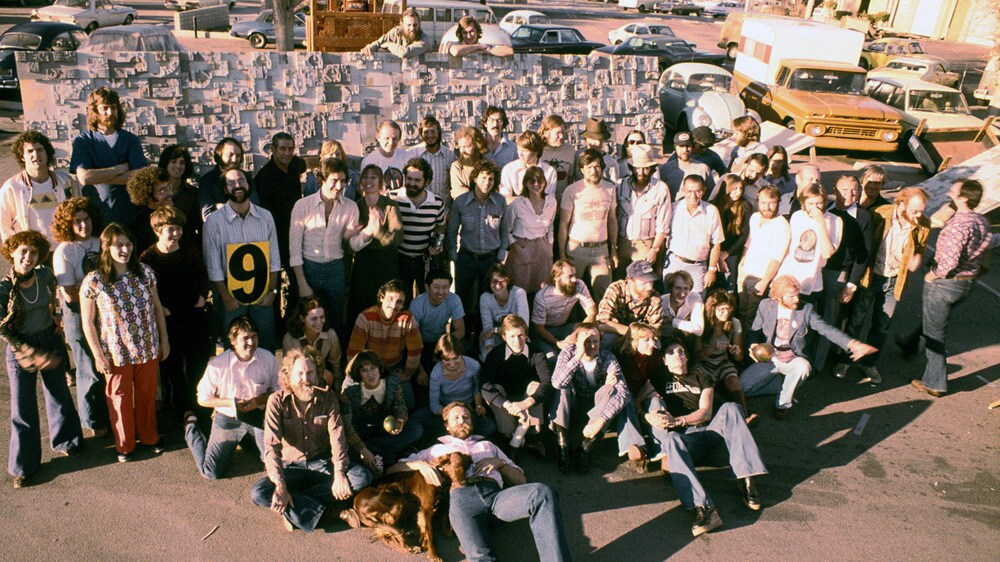

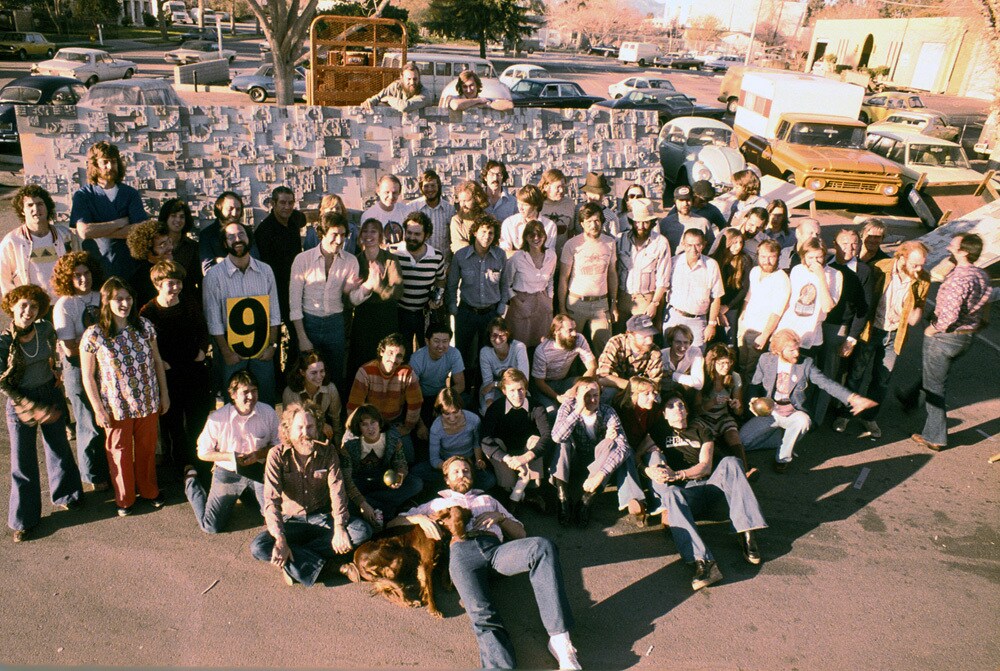

The ILM model shop may have been disbanded several years ago, but the men and women who made it great largely still live in the area. And not just the eight on the stage, but at least a dozen more who were standing around listening or running exhibit tables -- a bunch of them still making use of the skills they honed at ILM. Star Wars fans have always been fascinated by the behind-the-scenes people who made it happen, and the folks onstage are some of the best.

In the photo, they are (from left to right) Nelson Hall, Grant Imahara, Kim Smith, John Goodson, Larry Tan, Charlie Bailey, Lorne Peterson, and host Don Bies. There seemed to be several common themes. “I was hired for six months and stayed 16 years,” Tan noted. Goodson is still there, but years ago transitioned into CG work like a number of other current ILM longtime employees.

For Peterson, it was 35 years, and he was responsible for hiring a number of the other panelists. Long known as a great storyteller with an amazing memory, Peterson had a brief answer to how he got started in the business: “In the second grade a girl asked me to draw a house, and that was my entrée.” In 1975, as ILM was being pulled together, Lorne was doing sculptures for a McDonald’s project.

There weren’t a lot of model makers at the time, and many of the ILM employees came from art and industrial design backgrounds. Techniques were invented a step at a time. “They were using five-minute epoxy and tape to hold each piece onto a ship,” Peterson recalled. “Superglue was only being used for industrial applications at the time, so I brought some in, applied it to the end of a pencil, stuck it to the edge of a table and immediately let go. They were amazed!”

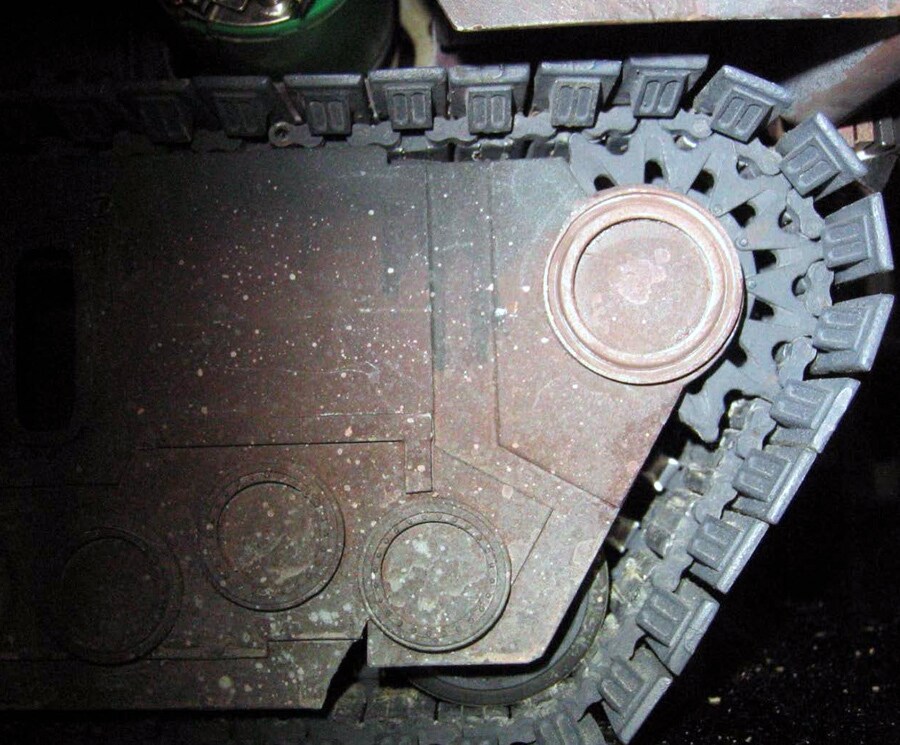

Each time one problem was solved, it was on to the next. Making individually-cast treads for the Jawa sandcrawler model was taking forever. Peterson wondered aloud why the model shop wasn’t using an injection molding machine. When he explained what it could do and that he knew where a used one could be had for $1,800, he was sent out immediately to pick it up.

“A lot of things started out with just seeing shapes,” Tan said. “You’d go to a flea market or a junk shop and just find these strange pieces you could use.” Goodson told of one time when a bunch of model makers went to a nearby building supply store and kept walking up and down aisles, pulling out all sorts of things from bins and holding them up to the light to see if the shapes would work for something. “You guys all work for ILM, don’t you?” asked the knowing lady behind at the cash register.

“There were stacks of old model kits that we could use for pieces, and drawers of ‘greeblies,’ or extras of parts that had been cast and used for something else,” said Imahara. “I used a miniature hubcap on a model for Space Cowboys, and when I went to see the movie, there was Clint Eastwood on the practical set with a three-foot-tall blow-up of that hubcap right behind him.”

One of the model shop’s longtime “secret” ingredients: walnut shells, often arriving by the ton in large palletized bags. They came in many different crush sizes and colors, from small pebbles down to fine sand and were used for everything from filling the Sarlacc pit model from Return of the Jedi to covering the surface of Geonosis in Attack of the Clones.

Sometime edibles were used, although that didn’t always work out well. “We were using sugary cake decorations as flowers for some of the Naboo building miniatures,” Tan remembers. “One morning we came in to shoot and we saw the flowers moving! We’d been invaded by an army of ants.”

There were lots of “Easter eggs” too, everything from a miniature Playboy centerfold inside the Star Wars Blockade Runner model to spelling out the names of one model maker and his girlfriend in piping on the front of the hospital ship at the end of The Empire Strikes Back. The roofs of most of the Theed buildings in Episode I had grass on top, so one day a jokester placed a miniature lawnmower on one; it still hasn’t been found on-screen.

And mistakes do happen, such as the fate of the $500,000 34-foot zeppelin that took the model shop two months to build for The Rocketeer. It was a laborious process because individual pieces had to be molded and cast for much of the ship; then they were scanned and laser-cut for the rest. Something went wrong with the pyrotechnics and the ship blew up backwards -- and mostly off camera. Amazingly, the model builders were able to build a new one in two weeks because of the laser scans.

Then there’s the famous shot in Empire of a battle-damaged AT-AT falling to its front “knees” before collapsing and blowing up. But the first time the shot was tried and a cable holding the AT-AT was cut, “it flopped down like a puppy dog, its head fell off, and smoke came out of its neck,” Peterson said.

One of Hall’s proudest achievements was for some items little seen on screen: faux rocks made to hide small cameras used to capture footage for the Academy Award-winning documentary The Cove, which looks at Japan’s legal mass dolphin slaughter.

It quickly became clear that the people on stage shared a lot more than the ability to make models; they were friends, yes, but even more a family. Several times they were asked about the future of model making in a digital age. “It’s still competitive in a lot of cases,” Bailey noted, “especially as the technology of showing a movie keeps getting better and you need things to look real.”

“In the last 12 months and for the first time since 2003, I’ve done more practical work than CG,” Smith said. “And the CG industry has really been hit hard in the last year or so.” To Smith there is really one key difference between sitting in isolation at a computer screen all day and working in a model shop. “You might have five people working on one piece and their hands and feet are all intertwined and… That’s a real team effort.” And one that the model makers will never forget.

(To see and read more about the hobby show itself: http://www.pressdemocrat.com/article/20130210/COMMUNITY/130219999)

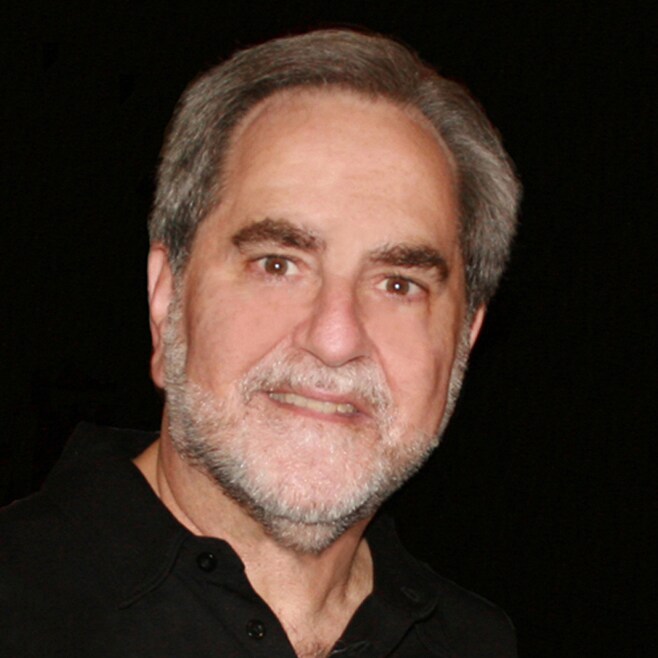

Steve Sansweet, fan relations adviser for Lucasfilm, is chief executive of Rancho Obi-Wan, a non-profit museum that houses the world’s largest private collection of Star Wars memorabilia. To find out about joining or taking a guided tour, visit www.ranchoobiwan.org. Follow on Twitter @RanchoObiWan and https://www.facebook.com/RanchoObiWan.